BY JOHN MAULDIN

It’s time to address the elephant in the room: the high-yield bond market.

That’s the polite name for “junk” bonds, issued by companies that can’t earn an investment-grade rating even from our famously lenient bond rating agencies.

This is a two-layer threat.

First, many of these companies are so marginal that even a mild economic downturn could render them unable to make bond payments. The second layer is that bondholders will want to sell those bonds. But the liquidity they presume probably won’t be there.

I could point to many examples, but we’ll take one that was in the news recently: WeWork.

WeWork Example

The still-private company issued bonds last month and gave the public a peek into the books. The offering raised $702 million at 7.875%—a nice yield if it lasts the full seven-year term.

But that is if you get your capital back at the end of those years. I’m not convinced investors will.

WeWork, at least, has a clear business model and superior execution. It signs long-term leases for office space, then subleases to the hordes of freelancers and independent contractors who need an inexpensive workspace.

Founder Adam Neumann is a charismatic executive who’s obviously adept at raising capital. So, it could last for some time.

The risk is that WeWork’s renters could disappear quickly if their own income dries up, as will happen for many when the economy breaks. Investors seem to believe this risk isn’t just manageable, but negligible.

Grant Williams featured a lengthy WeWork analysis in this month’s Things That Make You Go Hmmm… After walking through the numbers and comparing WeWork’s current $20 billion valuation with comparable companies, Grant says investors have essentially gone insane.

The list of investors’ concerns around WeWork belong to a bygone era when those lending a company their precious capital (and foregoing a risk-free return) used to require that company’s assets and liabilities bear some relationship to each other.

Negative cashflow also used to be ‘a thing’ and ‘strategic challenges’ once raised an eyebrow or two.

Not anymore.

Instead, in a world of yield-seeking and minimal due diligence, the combination of a (relatively) juicy yield and the appearance on a company’s register of superstar names like Masayoshi Son is all that’s required for what once counted as material aspects of a company’s business to be forgotten.

Grant isn’t the only skeptic, either. Developer John McNellis ran the numbers and reached this conclusion:

If, instead of merely subleasing 14 million feet, WeWork owned 14 million feet of office buildings at a valuation of say $500 a foot, the company would be worth $7 billion or roughly one-third of its self-touted value. And that $7 billion valuation would presuppose owning all of those buildings free and clear of debt.

McNellis also highlights something important from the bond disclosures:

WeWork neither signs nor guarantees its own leases; rather, for each lease it signs, it creates a single purpose entity [SPE] with very limited capitalization; i.e. its leases carry almost no financial exposure to the parent company. These entities are known as SPEs (“Screwing Probably Expected”).

So, if WeWork’s renters disappear, the first victims will not be WeWork, but the property owners who leased space to WeWork. They may have little recourse.

But they’re probably leveraged themselves, so the losses will flow upstream, eventually to the banking system. And we know where that ends.

Unraveling Dreams

Here’s the truly scary part: WeWork isn’t a black sheep. The landscape is littered with similar corporate borrowers. It is the inevitable consequence of a free-cash decade. Here’s Grant Williams again.

Ten years into the ongoing laboratory experiment being conducted by the world’s central banks, everywhere you look there are multiple examples of the kind of lunacy those policies have fomented by reducing the cost of capital to virtually zero and forcing investors to take risks they would ordinarily avoid in order to find some kind of return.

WeWork is one example of a company for whom, in the face of rapid growth, massive negative cashflows aren’t a problem, but there are plenty of others. Uber, AirBnB, SnapChat and, of course, Tesla have all captured the imagination of investors thanks to lofty dreams, articulated by charismatic CEOs—but the day things turn around and the economy begins to weaken or, God forbid, investors seek a return on their investment as opposed to settling for rolling promises of gigantic, game-changing revenues to come, it is over.

Look, I’m all about “lofty dreams.” I have them myself. I admire entrepreneurs who take risks and break new ground. They are the key to economic growth. Building a business is the single best and most effective way to create personal wealth.

But it’s also true that most of those dreams are simply dreams and will never come true. A few who bet on them win big, but most lose some or all of their investment.

Adam Neumann at WeWork has convinced investors that his office space rental company should actually be viewed as a technology company. We are creating a “community” he says. Whatever that is.

There is a successful and larger competitor whose valuation is roughly 10% of WeWork. But then, they are in the office space rental business, not the “creating a community/building the future” business.

A long line of businessmen and women seemingly have the gift to convince investors to buy unrated paper that is unsecured with no assets behind it.

The problem is that unraveling dreams tend to be contagious. Investor psychology is fragile, so the collapse of one high-profile dream can bring lesser-known ones down, too. I think we’re approaching that point.

End-of-Cycle Behavior

There’s something else interesting and a little counterintuitive happening.

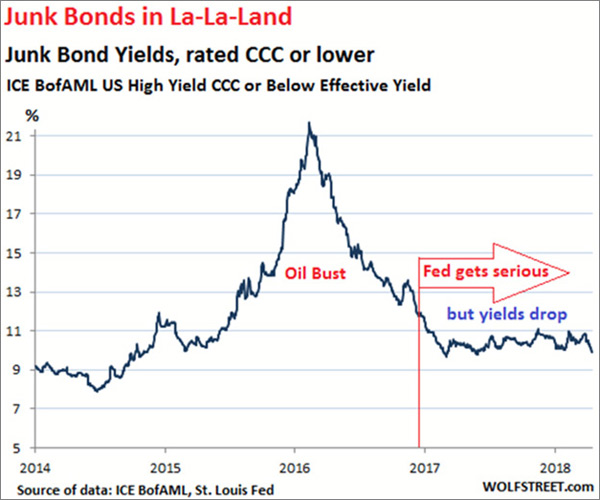

You might think the yield on bonds issued by risky companies would rise as the cycle matures. That would be consistent with investors demanding more compensation for their risk. But it hasn’t happened that way.

Source: Wolfstreet.com

After spiking higher during the 2015–2016 oil bust, when many shale drillers had serious problems, yields dropped in 2017.

Not by coincidence, that’s also when the Federal Reserve began hiking rates every quarter. Fearing capital losses, Treasury investors relaxed their credit standards and created more demand for junk bonds, which sent those yields lower.

That’s my theory, at least.

We’re seeing classic end-of-cycle behavior: throw caution to the wind and plunge capital into the market’s riskiest corners. This artificially-induced buying is propping up companies that would otherwise succumb to the fundamental forces arrayed against them.

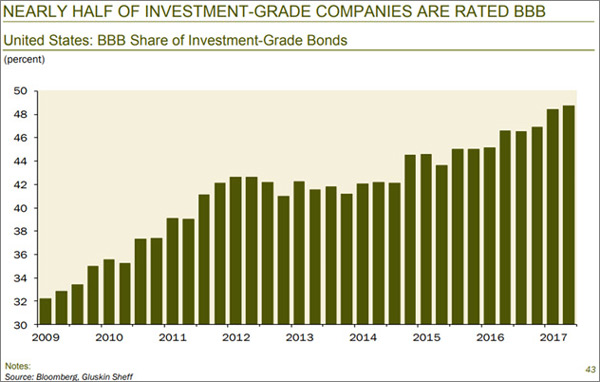

Nor is it simply a junk-bond problem; the investment-grade corporate market is becoming measurably riskier. Here’s a Dave Rosenberg chart that my friend Steve Blumenthal shared recently.

Source: On My Radar

Almost half of investment-grade companies are rated BBB, just one step above junk, up from just one-third in 2009.

When the economy breaks, some of those companies will run into trouble. Some of those will get downgraded, which will force many funds to sell them. This will intensify the liquidity storm I’ve described.

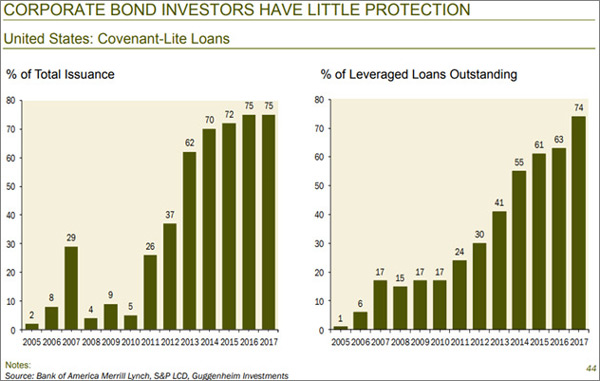

A few companies will probably default. Bondholders may have little recourse to recover their principal, having accepted covenant-lite conditions and taken on leverage themselves.

Source: On My Radar

Leveraged lenders will be in a pickle when the defaults begin, but they won’t be the only ones. It all flows downstream. Whoever extended credit to leveraged loan buyers will be in trouble, too.

That’s how problems in one market spread to others.