Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

“People are concerned about all that capital chasing limited opportunities.”

After a decade of “emergency” measures such as QE and zero-interest-rate policy designed to pump up asset prices – now ended – we get this:

“Everyone is worried where things are headed,” explained Matthew Anderson, managing director at Trepp a data firm focused on commercial real estate and commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS), speaking with The Wall Street Journal. “The basic complaint is that there’s a surplus of capital and a shortage of product.”

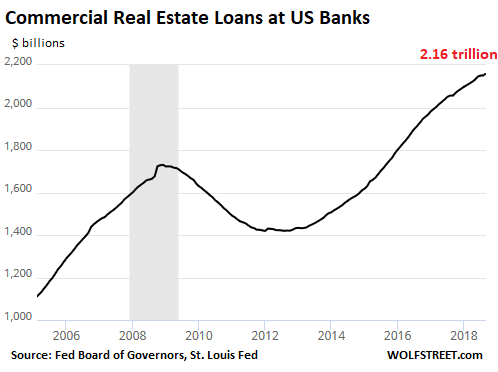

There are about $4.2 trillion in commercial real estate loans outstanding. Regulated banks hold just over half of it: $2.16 trillion, according to the Fed Board of Governors, with a majority of it concentrated at smaller banks (less than $50 billion in assets):

The other $2 trillion in CRE loans are held by non-banks, such as insurance companies, Government Sponsored Enterprises (such as Fanny Mae), and commercial mortgage-backed securities guaranteed by the GSEs.

Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren, who’d been warning about CRE and the risks it poses to the banks since 2016, gave a presentation in March 2017 on CRE’s risk to “financial stability.” His concerns over CRE was one of the factors that turned this dove into a rate-hiker and one of the first proponents of unwinding QE.

Other Fed pronouncements have also fingered repeatedly CRE loans as one of the risks to financial stability.

But since then, CRE loans have further ballooned, and a new force — private equity firms — has muscled into the space, heating up competition and leading to further lowering of loan underwriting standards – as all this capital is chasing product.

Private equity firms are trying to raise large amounts of money from pension systems and endowments, but also other investors, for these “debt funds” that then provide construction loans, bridge loans, and other types of often risky commercial real-estate loans.

There are now 106 funds trying to raise a total of $40 billion, according to the WSJ, citing data firm Preqin. In addition, real-estate debt funds already have $57 billion to invest, a new record.

Last year, CRE loan volume at PE firms jumped by 40% to $60 billion, according to the WSJ, citing Green Street Advisors. This gave those firms a market share of 10% in the CRE loan space, up from near zero in 2014.

And they’re all trying to chase product and deploy this capital they have already raised or are planning to raise. And they’re competing with each other and with everyone else. As result, risky lending has surged.

Back in 2012, interest-only CRE loans accounted for 30% of all CRE loans that were turned into CMBS. Because these loans don’t amortize, they’re considered riskier than regular mortgages. This was down from the peak of 60% before the Financial Crisis. For the first nine months this year, they accounted for 73%.

The waning credit quality, loosening lending standards, and rising interest-only loans that are packaged into CMBS have triggered a warning on Monday from Moody’s, which rates CMBS. While at it, Moody’s threw in a warning about falling collateral values:

- The credit quality of these loans “deteriorated.”

- “Leverage rose.”

- “Exposure to interest-only loans and single-tenant occupancy hit new highs.”

- “Underwritten-implied capitalization rates fell to their lowest average on record.”

- “Rising interest rates leave substantially more room for collateral values of recent vintages to fall than to rise.”

- “Rising rates also coincided with declines in debt service coverage ratios for the fourth quarter in a row.”

The latest numbers are “concerning to me,” Ricky Cipko, a Morningstar assistant vice president, told the WSJ. Now that the commercial property market is slowing, there are concerns borrowers may not be able to repay those loans.

“We’re seeing a lot more loans with cash flow that has crept down,” Steve Jellinek, a Morningstar vice president, told the WSJ.

Morningstar Credit Ratings had $25.4 billion of CMBS on its “watchlist” of securities that might face problems, up nearly 50% from the post-crisis low.

But it may get tougher for PE firms to raise the funds they aspire to raise. Treasury securities with maturities of seven years or longer now offer yields of over 3%, with near-zero credit risk. High-grade corporate bonds offer higher yields with relatively low risks, such as Apple’s 3.45% notes due in May 2024, which currently trade at a yield of 3.6%, according to Finra.

The record low cap rates in commercial real estate – the implied market cap rates used for underwritten property values fell to a record low of 5.87% in Q2, according to Moody’s – just aren’t that appealing anymore, given the big risks involved and the available alternatives.

So interest in real-estate debt funds “has plummeted,” with just 6% of investors in June saying the strategy “presented the best opportunities” over the next 12 months, down from 26% a year earlier, according to a Preqin survey released this month and cited by the WSJ.

“People are concerned about all that capital chasing limited opportunities,” Tom Carr, Preqin’s head of real estate, told the WSJ.

When investors stop chasing CRE deals at record low cap rates, and when pension systems stop plowing money into risky loan funds for very little return, it would mark a milestone in what the Fed calls a tightening of financial conditions, which is precisely what it wants to accomplish with its rate hikes and its QE unwind. So far, it has had only very limited success. But now it seems, the Fed’s medicine is ever so gradually starting to work.