Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

Asset-price inflation feels good to asset holders – until it doesn’t

I was asked two important questions in this mind-boggling era of QE: The Bank of Japan has monetized 50% of its national debt; so why has there not been a surge of inflation? And why can’t the Fed restart QE and do the same without triggering inflation?

“Inflation” can be a lot of things. Here we’re not talking about “monetary inflation.” We’re talking about price inflation – when the currency loses its purchasing power. There are several types of price inflation that are accounted for separately, including:

- Consumer price inflation

- Wholesale price inflation

- Wage inflation.

- Asset price inflation.

The questions were about consumer price inflation; but the answer lies in asset price inflation.

It’s true that despite QE globally – not just in Japan – there has been relatively little consumer price inflation in the countries whose central banks perpetrated it. But it has caused enormous asset-price inflation. We call it the “Everything Bubble” where practically all asset classes globally have become ludicrously inflated.

Asset price inflation means that the currency loses purchasing power with regards to assets, such as real estate. The house is the same, only a little more run-down, but now it takes twice as many dollars to buy than five years ago.

When asset-price inflation reverses, which it invariably does, it can be deadly for the banks and the financial system overall. There are plenty of examples, including the US housing and mortgage crisis that was part of the Financial Crisis.

Assets are used as collateral by banks and other lenders. When asset prices get inflated, they support larger loans. But inflated asset prices invariably deflate at some point, and suddenly, when the borrower defaults, the collateral is no longer enough to cover the loan. Asset price inflation feels good because it translates into free and easy wealth for asset holders, but when it deflates, it tends to bring down the banks – even or especially the biggest ones – and causes all kinds of other mayhem.

Asset price inflation means risks are building up in the financial system.

So central banks, while they try to stimulate some asset price inflation, are worried when it goes too far. The Fed has expressed this worry in various forms for two years. The ECB is now murmuring about it. And even the Bank of Japan is suddenly fretting about the “sustainability” of its QE program, and its impact on the financial markets.

This is why QE cannot be maintained without setting the stage for another, and much bigger and even more magnificent collapse of the financial system, the Big One if you will, and all the real-economy mayhem it would entail.

Consumer price inflation – defined here as loss of purchasing power of the currency with regards to consumer goods and services, as measured by a consumer price index – is in part a confidence game.

Consumer price inflation results from a mix of market forces, psychology, and other factors. What exactly causes consumer price inflation is still not fully understood, as evidenced by the surprise that economists experienced when QE failed to cause it.

One factor in consumer price inflation is confidence in the currency – often measured as “inflation expectations.” Like so many other factors in economics, it’s psychological!

When the people have confidence that the purchasing power of their currency remains stable, and when businesses therefore cannot raise prices because people and other businesses would refuse to pay these higher prices, then inflation is “well anchored,” as central bankers say. This is expressed in various “inflation expectation” indices. But confidence can vanish, and once gone, it’s devilishly hard to rebuilt.

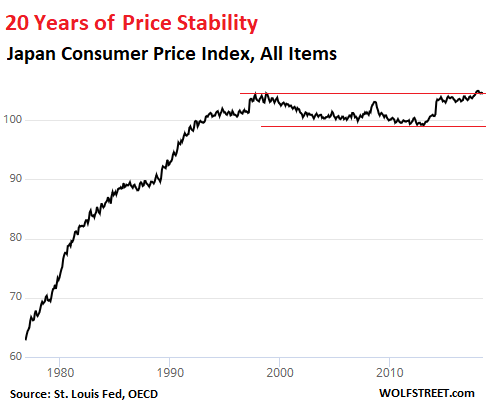

Over the past two decades, the Japanese have learned that there is very little or no inflation in their system:

All economic players have adjusted to it — consumers, government entities, businesses, pension funds, etc. This confidence has made it effectively impossible to raise prices on many goods and services (with some exceptions). When companies tried to raise prices, consumers simply switched to alternatives or cut back, and the price increases didn’t stick.

The Japanese are hording cash (via yen deposits and other low-risk yen instruments) because they know it will retain its purchasing power. They trust the yen! This attitude – “inflation expectations” – has helped keep inflation to near zero. It’s a self-reinforcing mechanism.

On the other hand, there’s Argentina: Successive governments have for decades trashed any kind of confidence or trust people might have had in the peso. Argentines get rid of pesos as soon as they can (convert them into dollars or assets). In other words, they constantly sell pesos. The entire economy has adjusted to dealing with a currency that rapidly loses purchasing power. It too is a self-reinforcing mechanism.

During the 1970s, there was a lot of inflation in the US, reaching nearly 15% in 1980. It had to be stopped before it would spiral completely out of control. Fed Chairman Paul Volcker, with the gutsy public backing of President Reagan, went to work with rate increases of a full percentage point per meeting that shocked. This was accompanied by a publicity campaign.

It was radical surgery to rebuild confidence in the dollar, and it caused a nasty “double-dip” recession that threw millions of people out of work. But inflation began dropping. And over many years, it gradually rebuilt confidence that prices might rise by about 2% to 3% a year, not more. In the Fed’s terms, “inflation expectations are well anchored.” As long as that confidence persists, inflation will have a hard time spiraling out of control.

But in the US, this confidence is still fragile. Inflation expectations already ticked up to 3%. Once inflation expectations rise, all bets are off.

This can also crop up in Japan, and when it does, nothing and no one will be prepared for it – after two decades of price stability. If consumer price inflation gets out of hand, the loss of purchasing power of the yen will destroy much of the wealth of the Japanese and the purchasing power of their labor.

That is a risk. And it comes on top of the more immediate risk associated with asset price inflation – what it does to the financial system when the prices of leveraged assets deflate. That’s the mechanism by which QE becomes destructive. That’s why the price of free money can be very costly.