via zerohedge:

One month ago we wrote that in the aftermath of the shocking government May 24 seizure of Baoshang Bank – not shocking because the bank failed as most Chinese banks are insolvent if left to their own devices due to the real, and far higher levels of non-performing loans, but because the government allowed it to happen in the open, sparking fears of who comes next (and when) – the PBOC “finally panicked and injected a whopping net 250 billion yuan ($36 billion) into the financial system via open-market operations, as it fills what traders have dubbed a growing funding gap following the Baoshang failure.”

In retrospect, the PBOC failed to restore confidence in the stability of the Chinese banking system, and since then things have taken a turn for the far worse.

Yet with the world fixated on the U.S.-China (Mexico, Europe, etc) trade conflict, it is easy to understand why many have brushed aside the Baoshang harbinger and its consequences which have exposed giant fissures under China’s calm financial facade and are gradually freezing up the Chinese banking system.

As the WSJ writes, on Sunday, China’s securities regulator convened a meeting asking big brokerages and funds to support their smaller peers, according to a meeting summary circulated among industry participants Monday. The briefing cited rising risk aversion in money markets after defaults in the bond repurchase market.

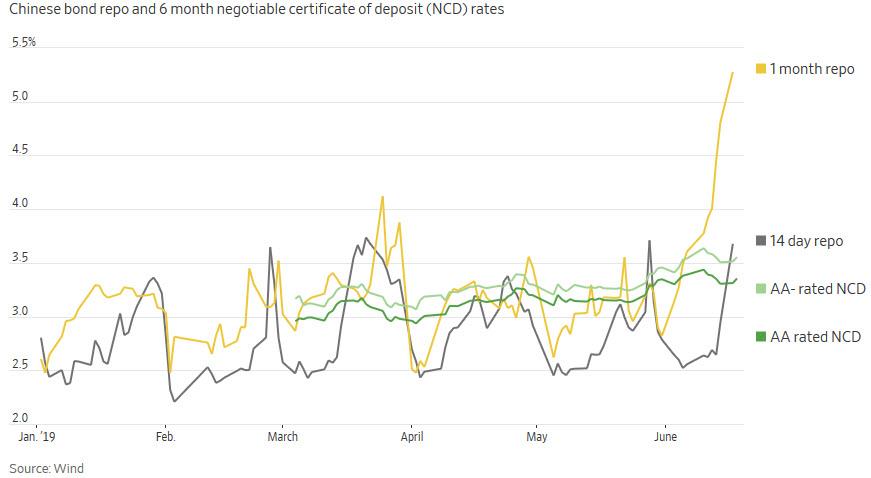

The immediate reaction, which we pointed out back in May, is that some of the key interbank lending rates – those which banks rely on to obtain critical short-term funds – have moved sharply higher in recent weeks, with the 1 month repo soaring, and almost doubling over the past month.

For those who are only now catching up with this extremely important story, here is the background context: as we explained last month, and as the WSJ recaps, China’s short-term lending market for banks and other financial institutions has for years operated under the assumption that Beijing wouldn’t allow big losses in the event of defaults or insolvencies (hence the reason why Baoshang’s failure was a shock). That confidence has been shaken by regulators’ unusual public takeover of the troubled Chinese bank near Mongolia last mont, and the even more stunning public admission by the central bank that “not all of Baoshang Bank’s liabilities would necessarily be guaranteed.”

“Bank failure always causes greater concern given systemic fears,” said Owen Gallimore, head of credit strategy at Australia & New Zealand Banking Group, suggesting greater pressure on the private sector ahead.

Naturally, with China growing at the slowest pace in recent history, beset by shadow bank deleveraging, trade war, a shaky transition to a consumer economy and China’s first ever current account deficit, these stresses come at a very bad time for the normal functioning of the local economy.

Meanwhile, nonbank financiers like brokerages and funds are key supporters of embattled private businesses, since they buy a significant percentage of corporate bonds. They are also far-and-away the biggest net interbank borrowers, following a 2016 crackdown on short-term borrowing by banks to fund leveraged wealth-management products.

Furthermore, nonbank borrowing through bond repos and interbank loans skyrocketed since China’s central bank began easing monetary policy in early 2018, hitting a net 74 trillion yuan ($10.7 trillion) in the first quarter of 2019, according to Enodo Economics, and up nearly 50% from a year earlier. As the WSJ redundantly warns, “funding troubles for brokerages and other asset managers therefore pose big problems for both financial stability and the real economy.”

Meanwhile, as we warned as far back as March 2017, problems appear to be migrating from the smallish market for negotiable certificates of deposit (NCDs), used mostly by small banks, into the vastly greater bond repo market. Here, while key one-day and seven-day weighted average borrowing rates remain low thanks to huge central bank cash injections – such as the 250BN yuan we described back in May – longer tenors such as the 1 month repo have marched sharply higher (see top chart).

As an aside, for those asking why NCD’s matter, the answer is because as we first explained two years ago, numerous smaller banks had become acutely reliant on such shadow banking funding mechanisms as Certificates of Deposit, which had become the primary source of short-term funding for many of China’s banks mid-size and smaller banks.

As Deutsche Bank further explained, the banks most exposed to a shut down in this “shadow funding” pathway are medium-sized and small banks – such as Baoshang – for whom wholesale funding made up 31% and 23%, a number that has risen substantially in the interim period.

Some more background: in China, the funding flow goes like this (per Bloomberg): big national banks lend to smaller regional lenders, which then provide financing to non-bank peers such as brokerages and funds. They in turn use the money to invest in corporate bonds.

“Smaller banks play a key role in this chain,” said Ming Ming, chief fixed-income analyst of Citic Securities Co. Right now investors are quite “risk averse and everyone wants to mitigate counterparty risks. If things get worse, China’s financial market liquidity could collapse,” he added.

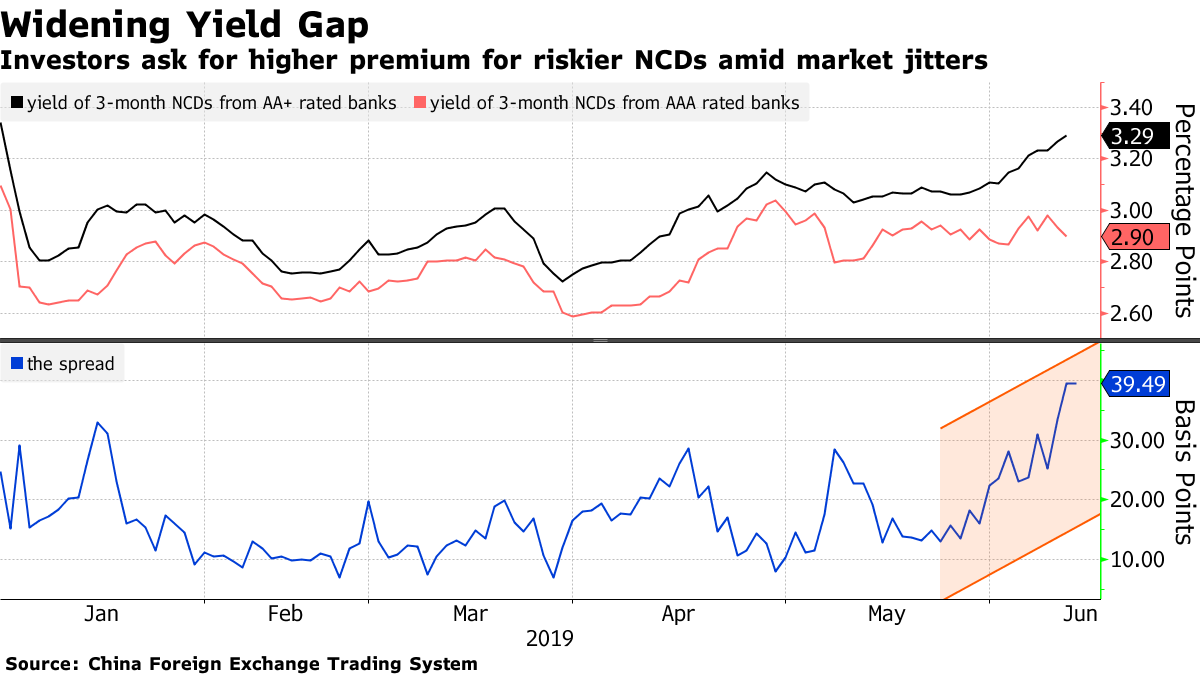

In this context, the issue of NCD funding is especially troublesome, because as Bloomberg reported recently, in the aftermath of the Baoshang seizure, some Chinese banks and securities firms “tightened requirements for negotiable certificates of deposits that are used as collateral for funding.” In some cases, private NCDs were shunned altogether, and some financial institutions now only accept NCDs sold by state-owned and joint stock banks as collateral while some have refused to lend money to investors pledging NCDs issued by lenders rated AA+ and below for now.

Worse, as Bloomberg followed up over the weekend, the interbank market is now also freezing up as a result of counterparty suspicions: one month after Baoshang, Chinese bond traders in China are “rethinking counterparty risks as shock waves from a government takeover of a bank ripple through the country’s financial markets.”

In ominous echoes of what happened before, and certainly after the Lehman failure, it has gotten far harder for corporate bonds to be accepted as collateral for repo financing as lenders increasingly demand top quality bonds such as Chinese sovereign bills and policy bank notes as pledges, with Bloomberg noting that “traders are having second thoughts on taking even AAA rated short-term bank debt as security in the wake of last month’s seizure of Baoshang Bank”

As a result, funding among China’s financial institutions has become clogged, in some cases to the point of paralysis, which have already caused borrowing costs to spike for brokerages and smaller banks . The timing couldn’t be worse, not only due to China’s slowing economy, but with liquidity traditionally far tighter at the quarter-end, and further adding to the wide-ranging ramifications of the bank seizure. All this could mean higher defaults, according to Bloomberg Economics.

“Non-bank financial institutions are actually the biggest buyers of corporate bonds in China, and if their funding chain breaks, demand for bonds, particularly those that can hardly be pledged for borrowing, will certainly get hurt,” said David Qu at Bloomberg Economics in Hong Kong. “Weaker companies will suffer a rising cost when selling new bonds, which may eventually lead to higher default risks.”

And while seasonal cash demand ahead of the quarter-end is probably playing a role, the WSJ adds that small banks, squeezed out of the market for NCDs, may also be trying to replace a portion of three or six-month NCD funding in the repo market (again, see the surge in the one-month repo rate which has nearly doubled from 2.9% to 5.2%).

So is this China’s (long overdue) Lehman moment?

There is some good news: one reason for optimism is that the Fed is looking dovish, and may cut rates as soon as today. Last time China’s money markets got worried about counterparty risk in the aftermath of brokerage Sealand Securities’ initial refusal to pay out on a repo-like agreement in late 2016, the Fed was in tightening mode. As the WSJ’s Nathaniel Taplin writes, “a dovish Fed gives China’s central bank more room to cushion any further money-market ructions with ample liquidity without worrying too much about destabilizing capital outflows.”

It’s not all good news however: unlike now, in late 2016 China’s economy was improving and so was corporate creditworthiness. That is no longer the case, and as such, investors should keep a very close eye on China’s money markets in the days ahead to make sure a seasonal cash crunch and problems at a few banks and brokerages don’t result in broad contagion and “contaminate a fragile financial ecosystem”, one which as the Baoshang shock of May 24 shows, is no longer unreservedly backstopped by Beijing.