Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

After the hullabaloo on Wall Street and in the media about the comments made by Fed Chairman Jerome Powell and Vice Chairman Richard Clarida this week, the Fed released the minutes of the FOMC meeting on November 7-8. The WOLF STREET Fed hawk-o-meter checks the minutes for signs that the Fed believes the economy is strong and that “accommodation” needs to be further removed by hiking rates. And this is shedding some light on the recent comments.

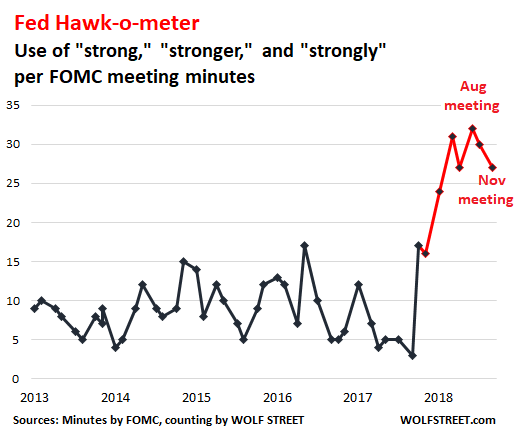

My only slightly tongue-in-cheek hawk-o-meter measures how many times the minutes use the word “strong,” “strongly,” and “stronger.” In the minutes, released on Thursday, mentions of “strong,” “strongly,” and “stronger” edged down for the second time in a row, to 27, same as in the June meeting minutes, and down from 30 in the September meeting minutes, and from the record 32 in the August meeting minutes. But in this range, the hawk-o-meter is still redlining:

The average frequency of “strong,” “strongly,” and “stronger” between January 2013 and December 2017 was 8.7 times per meeting minutes. In the November meeting minutes, it was 27 times – an increase of 210% from average.

The average over the past five meeting minutes (May, June, August, September, November) was 29.4 times.

These expressions of “strong,” “strongly,” and “stronger” appear in phrases like these:

- “Real gross domestic product (GDP) rose at a strong rate in the third quarter….”

- “Total nonfarm payroll employment increased at a strong pace….”

- “Real PCE [inflation adjusted consumer spending] continued to grow strongly….”

- “The labor market had continued to strengthen and that economic activity had been rising at a strong rate.”

- “Job gains had been strong, on average, in recent months….”

- “Household spending had continued to grow strongly….”

But there were also references to “moderated,” particularly in regards to business investment, but also some other spots, for example:

- “Growth of business fixed investment had moderated recently from its rapid pace earlier in the year.

- “Growth of business fixed investment has moderated from its rapid pace earlier in the year.”

- “Growth in real private expenditures for business equipment and intellectual property moderated in the third quarter….”

- “Credit card loan growth showed signs of moderating….”

So this economy is still rocking and rolling, according to the minutes, but there are a few spots where the beat slowed down a little.

Assuming the economy continues on this track, the meeting participants penciled in the fourth rake hike in 2018 for the December 18-19 meeting: “Almost all participants expressed the view that another increase in the target range for the federal funds rate was likely to be warranted fairly soon.”

This rate hike at the December 18-19 meeting would bring the Fed’s target for the federal funds rate to a range between 2.25% and 2.5%. This is up from a range between 0% and 0.25% before the Fed started raising rates three years ago.

The “effective” federal funds rate, as of today, is 2.20%. Since last year, it has been near the top, rather than in the middle, of the Fed’s target range, somewhat perplexing the Fed and causing it to make a minor adjustment to the interest on excess reserves (IOER) that it pays the banks in order to bring the federal funds rate into the middle of the target range, so far without success.

At this pace, the effective federal funds rate may be around 2.45% after a December hike. So how far below “neutral” would this 2.45% be?

The “neutral” federal funds rate is a theoretical concept rather than a hard number. It’s the federal funds rate that would be high enough to not stimulate the economy and low enough to not slow it down either. Every member of the FOMC projects what this “neutral” rate is in their opinion. Their projections range from 2.5% to 3.5%, with the median projection of 3%. This is where “neutral = 3%” comes from.

After the December hike, it would only take two more rate hikes to get the federal funds rate within a hair of the median projection of “neutral.”

When Powell said in his speech a couple of days ago, that the federal funds rate was “just below” neutral, it was in light of these numbers. No one knows what “just below” means – so one hike in December and one or two rate hikes next year? And after the Fed gets to its “neutral,” wherever that may be, what’s next? Powell left it purposefully to our imagination, and Wall Street sure imagined God knows what.

The minutes also said that FOMC members thought that the post-meeting statements might have to be modified in the future, “particularly the language referring to the committee’s expectations for ‘further gradual increases.”’

Many participants indicated that it might be appropriate at some upcoming meetings to begin to transition to statement language that placed greater emphasis on the evaluation of incoming data in assessing the economic and policy outlook; such a change would help to convey the Committee’s flexible approach in responding to changing economic circumstances.

Sure, as the rate gets closer to neutral, the language about future clockwork rate increases will need to be revised. And why should there be any references to future rate hikes? This type of “forward guidance” is an invention of the Bernanke Fed. The Powell Fed has been discussing for months to get away from forward guidance to free its hands and re-introduce a level of surprise in each of its meetings starting in 2019.

And just so that the dovish interpretations don’t go overboard, there was a reference in the minutes to the Fed’s nervousness about “the high level” of debt among nonfinancial businesses (banks excluded):

Several participants were concerned that the high level of debt in the nonfinancial business sector, and especially the high level of leveraged loans, made the economy more vulnerable to a sharp pullback in credit availability, which could exacerbate the effects of a negative shock on economic activity.

This potential “negative shock” from the direction of business debts, including commercial real estate, that could impact financial stability is a central topic in the Fed’s first Financial Stability report released this week, which I will cover next.