Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

“When times are tough, the thinking switches to the short-term. Many fleets are just fighting for survival.”

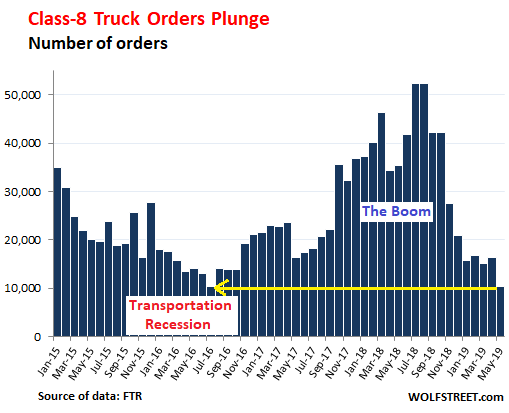

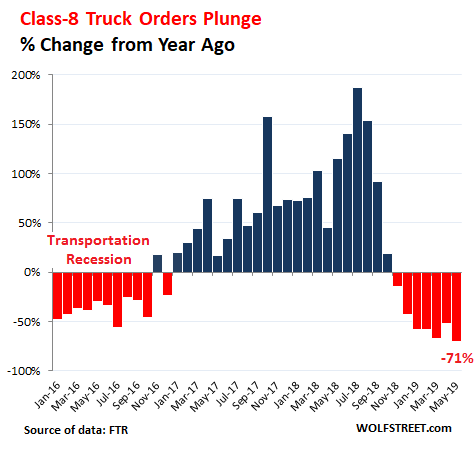

Orders for Class-8 trucks – the heavy trucks that haul a large part of the goods-based economy across the US – plunged by 71% in May compared to May last year, to — as FTR Transportation Intelligence called it this afternoon — a “chilly 10,400” orders. It was “the lowest volume for Class 8 orders since July 2016 and the weakest month of May since 2009,” FTR said in the statement (data via FTR):

This comes after orders had already plunged year-over-year by 52% in April, 67% in March, 58% in February and January, and 43% in December. It was the seventh month in a row of year-over-year declines (data via FTR):

The cyclical nature of the industry is legendary. Trucking companies get exuberant when capacity tightens and freight rates soar – which they did in late 2017, that in 2018 turned into an outright capacity shortage and a driver shortage.

This boom was fueled in part by a decision in Corporate America to build up inventories in the US to front-run potential import tariffs. This put additional pressure on trucking capacity, and on freight rates. And it motivated trucking companies to order new equipment to meet demand. Given the capacity pressure at the time, they tried to get the orders in ahead of the others, and this created a phenomenal boom in orders — and at truck manufacturers, historic order backlogs.

Then the other part of the cycle begins. As these new trucks enter service, capacity rises, taking pressure of the system. This was expected.

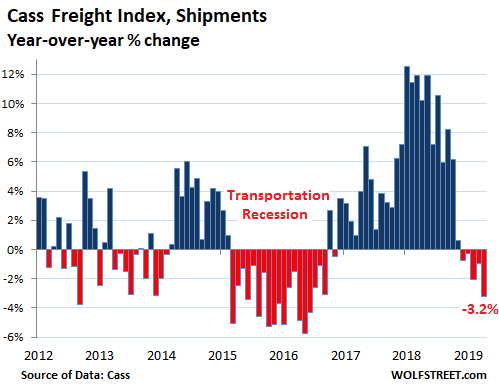

But then the unexpected happened: Demand backed off late last year. And April was the fifth month in a row of falling freight shipment volume in the US across all modes of transportation – by truck, rail, air, and barge – according to the Cass Freight Index, the first series of declines since the transportation recession of 2015 and 2016:

Craig Fuller, CEO at FreightWaves, wrote in an editorial about the duality currently in the market: Contract rates are barely hanging on, and large trucking fleets with big committed customers are able to benefit from those; but spot rates, on which smaller trucking companies are dependent, “have dropped like a rock” – by 36% from the peak in June 2018:

The reason – the market has been oversupplied with capacity. Carriers, big and small, added to their fleet counts last year. While carriers struggled to find drivers to seat those trucks, higher driver pay and incentives did generate successful outcomes.

The “driver shortage” and “capacity shortage” are two different things. The driver shortage commonly refers to the availability of drivers in the market to drive the trucks that are on fleet rosters, while the capacity shortage is a function of having enough trucks available for dispatch.

Unseated trucks don’t generate revenue, while a capacity shortage gives the fleets pricing power as shippers and brokers struggle to find capacity. And in markets with a capacity shortage, carriers and drivers alike are big winners. Nothing brings driver pay up like a good old capacity shortage.

When times are good, carriers are eager to grow their fleets and attract the best drivers, which means they roll out the best perks and incentives to get the drivers to join their fleet.

When times are tough, the thinking switches to the short-term. Many fleets are just fighting for survival.

And truckers are adjusting their orders for new equipment. At the moment, the historic backlog of Class-8 orders that accumulated during the boom in 2018 is keeping truck manufacturers on their toes.

But during the transportation recession, Paccar (Peterbilt and Kenworth), Navistar International, Daimler (Freightliner and Western Star), and Volvo Group (Mack Trucks and Volvo Trucks) and their suppliers, such as diesel-engine manufacturer Cummins, laid off waves of workers. But for now, this is not on the horizon.

The backlog is expected to shrink to about 220,000 orders, which will keep build rates “at robust levels,” FTR said in the statement today. This is down to nearly half of the record backlog of 411,000 orders at the peak last summer, according to FTR at the time.

May was the last month of the order cycle. And in June, some manufacturers will start taking orders for next year. And that will be the moment of truth.

“The economy and freight growth are expected to ease throughout the year, applying some downward pressure on the truck market in the second half,” said Don Ake, FTR vice president of commercial vehicles. “Orders for the next couple of months should be a good indicator of fleet confidence about 2020.”