via themacrotourist:

It seems like a lot of hard-money-hawks were caught off guard by last month’s dovish shift by Powell. I have had more than a couple of conversations with different market participants who have expressed disbelief about how quickly Powell abandoned his tough “we-won’t-let-market-conditions-influence-our-monetary-decisions” policy. These Powell-disciples are rightfully feeling a little betrayed. After all, Powell promised he would tune the economy to the real economy, not the financial economy. For these new-era hawks, the problem of the last decade has been a FOMC board that has caved to every hiccup in the stock market. They have argued that in the long run, these policies create an economic environment filled with excesses and mis-allocated resources which ultimately leads to less growth. They were excited to finally have a non-academic business-person in the FOMC Chair that recognized this reality.

I understand their point of view. And although I am not smart enough to judge correct policy, I have been around the block enough to know the chances of their policies being enacted is about high as Salma Hayek phoning me up to go out for coffee (see High Debt Levels Rant for backstory).

It was easy for Powell to mouth words about not being beholden to each market tick when the stock market was shooting higher. It didn’t take much courage to stress the long-term-soundness of money when financial conditions were easing.

But really, why was Powell so intent on establishing such a hawkish tone?

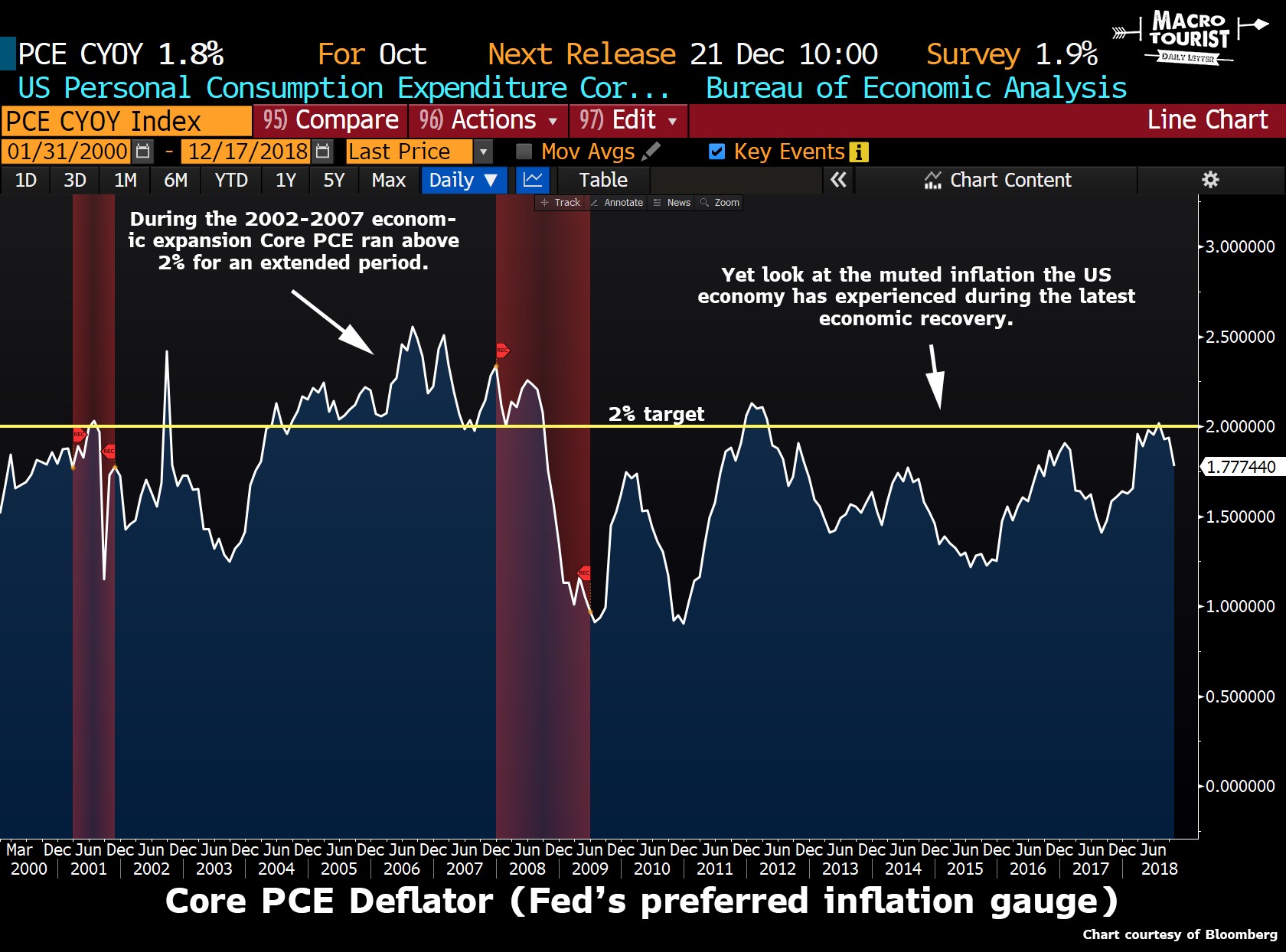

After all, have a look a the Federal Reserve’s preferred measure of inflation – the Core PCE Deflator – over the past two decades:

You might disagree with the Fed targeting 2% inflation. Yeah, I get it. it is arbitrary and could very well be improper policy. But here is my advice. Instead of spending your money fighting the market hoping for the Federal Reserve to realize that 0% is a better target, take that money and run for office so that you can change policy. As I repeat time and time again, trade the market in front of you, not the one you want.

Like it or not, the Federal Reserve has a 2% inflation target and the reality of the current economic cycle is that there have only been five months when inflation has ticked above their target. If we accept that the Fed’s 2% target is a not a ceiling but a long-term average that the Fed is aiming for, then it makes Powell’s hawkish stance all the more peculiar.

Here’s my take. When Powell took office, financial markets were rocketing higher due to Trump’s pro-growth tax cuts. Financial conditions were easy and it looked like another bubble was forming. So Powell took the opportunity to lean against the froth and adopt a hawkish bias.

Ironically, this caused financial conditions in the United States to ease even further as capital stormed in. In the current environment where most Central Banks are actively engaging in financial repression, Powell represented a welcome change. Capital goes where it is treated best, and for most of 2018 that was the United States.

As the money kept pouring in, financial conditions continued to ease, and Powell became more emboldened to become even more hawkish. The market pundits who had long argued against easy money policies pointed to the massive US financial market outperformance and proclaimed that America was drinking the world’s milkshake.

But then something happened October 3rd when Powell said the US was “still quite a ways from neutral.”

The self-reinforcing reflexive capital-attracting-cycle of Powell’s hard money stance hit the point of saturation. At that point the yield curve started to invert (or at least kink) and risk assets sold off hard. Powell finally tightened too much.

Now, this is where it got really interesting. Those who had taken Powell’s comments at face value were convinced that he wouldn’t shift policy simply because the stock market dipped a little. After all, in the grand scheme of things, financial markets were still elevated. What’s 350 S&P points when the stocks market is up 2300 over the past decade? Surely Powell will not cave at the first dip.

Wrong. He folded like a lawn chair.

And now here we are a few days away from the next FOMC meeting, and many of these hard-money pundits are still predicting Powell will walk back his dovish tilt.

A good trader knows to never say never, but I think the chances of that happening are extremely low. What’s the point? Inflation is running below target. Risk assets are selling off hard. Why take the chance that a hawkish comment from the FOMC causes the next crash?

The only real susprise

The fact that Powell is doing what every Fed Chair before him has done (err on being easy) is not a surprise. The only real surprise is that he lasted this long before caving into the pressure. Powell is no second-coming of Volcker the hawks fantasize about.

The simple fact is that there are no atheists in foxholes. Especially when there is so little to gain from a hard-money stance.

If Core PCE was running 4%, then I might be sympathetic to the argument that Powell will hang tough and take the pain. But it’s not. It’s running below target and has been for the whole recovery.

It just got a whole lot harder for Powell to remain hawkish

If you remember back to when President Trump was making the decision for the next FOMC Chair, one of the front-runners was Kevin Warsh. The hard-money hawks were positively giddy about the possibility that Warsh be appointed. After all, Kevin was extremely critical of Bernanke/Yellen’s easy money policy in the aftermath of the Great Financial Recession.

But Trump ultimately decided against putting a hard-money guy in charge of the price of money (shock) and chose a practical businessman that he hoped would thread the needle. Much to Trump’s disappointment, Powell has been way more tight than Trump would have ever predicted.

Yet that’s old news. We all know Trump is not pleased with his choice in Powell, “not pleased even a little bit.”

What’s amazing is that over the weekend, Kevin Warsh and Stanley Druckenmiller – two of the most outspoken critics of the easy-money-policy of past Fed chairs – have penned an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal that argues Powell needs to stop tightening… immediately.

In an article titled “Fed Tightening? Not Now”, the two argue the Federal Reserve has gone too far and risks causing a market crash that will have profound ramifications:

Around Oct. 1, global central-bank liquidity reversed and stocks began their descent from peak prices. That is no coincidence. The Federal Reserve should take an important signal from recent developments at its meeting this week.

As we head into 2019, quantitative tightening is expected to accelerate. It has been paired with expectations of interest-rate increases from the Fed – and the timing could scarcely be worse.

Economic growth outside the U.S. decelerated over the past three months. Global trade growth also slowed markedly, running about one-third lower than earlier in the year. Growth in some important economies, like China, is significantly weaker. No ocean is large enough to insulate the U.S. economy from slowdowns abroad. And no forecasting model adequately captures the spillovers and spillbacks between the U.S. economy and the rest of the world.

U.S. financial-market indicators also signal caution. Market prices may be showing their true colors for the first time since QE’s expansion. These indicators aren’t foolproof, but they have a better track record than economists. Bank stocks are down about 15% since Oct. 1. Other economically sensitive sectors, like housing, transport and industrials, are down by double digits, underperforming the broader markets. Credit markets are softening, and the decline in major commodity prices is foreboding.

These indicators are at odds with strong U.S. economic growth for 2018, which will come in at around 3.25%. Labor markets also remain strong, although they too are a lagging indicator.

The new Fed leadership team faces the most difficult challenge since Chairman Ben Bernanke and his team confronted shocks to the financial system in 2007-08. They deserve forbearance, not censure. But time is tolling, and the Fed is well-advised to break from the old regime.

The Fed should worry less about fine-tuning its communications strategy and more about getting policy right. In recent months, Chairman Jerome Powell stepped up outreach to Congress and other interested parties. He spoke with refreshing humility about the appropriate policy rate setting. And he prudently scaled back on the kind of pinpoint forecasts his predecessors made. These moves, while welcome, are insufficient.

In response to market tumult, the Fed governors recently hinted at less enthusiasm for rate increases next year. The new forward guidance is different from what they signaled in September. But it is no more reliable. The Fed should stop this option-limiting exercise entirely. And if data dependence is the Fed’s new mantra, it should actually incorporate recent data into its forthcoming policy decision.

The Fed’s balance sheet is where the money is. Yet it has provided little additional clarity on its balance-sheet plans since Chair Janet Yellen’s tenure. At a time of global quantitative tightening and uncertain economic prospects, the Fed’s silence on its asset holdings is contributing to the tumult.

The time to be dovish was when the crisis struck and the economy needed extraordinary monetary accommodation. The time to be more hawkish was earlier in this decade, when the economic cycle had a long runway, the global economy ample momentum, and the future considerably more promise than peril.

This is a time for choosing. We believe the U.S. economy can sustain strong performance next year, but it can ill afford a major policy error, either from the Fed or the rest of the administration. Given recent economic and market developments, the Fed should cease – for now – its double-barreled blitz of higher interest rates and tighter liquidity.

This op-ed is a way bigger deal than most the market participants currently appreciate.

Sure, you can complain all you want about how Stanley and Kevin talk tough until risk assets sell off, but then quickly shift to the dovish side. Or you can claim that they are trying to talk their book, but the reality is that Stanley can make just as much money on the short side as he can on the long side, so I don’t buy that one bit.

Regardless, all I care about is what this means for the market.

And having the biggest legitimate hawk out there – Kevin the “ferrugineous rough-legged hawk” Warsh – publicly advocating for easier monetary policy has given tons of cover for Powell to err on the dovish side.

Don’t overthink this. Don’t sit around trying to imagine all the ways Powell will push back on Warsh’s op-ed. There is little reason for him to do so. You might want him to do that, but he isn’t going to. Who knows? Maybe Powell is glad that Kevin and Stan wrote the piece. Heck, Jay might have even asked Kevin for some cover.

I don’t have the answers to what should be done, but I have an educated guess on what will be done. And it’s obvious the days of relatively hawkish US monetary policy are behind us. The surprises will not be how high Powell takes rates, but rather, how quickly he gives up on that idea and reverses course.

Thanks for reading,

Kevin Muir

the MacroTourist