Authored by Phillip Magness via The American Institute for Economic Research,

Are the poor actually paying a larger share of their earnings in taxes than the ultra-wealthy? That’s the claim at the center of a new New York Times article purporting to trace the effects of the previous year’s tax cut package.

While supporters of wealth taxation quickly claimed vindication for their cause in these findings, a closer examination provides several clear signs that something fishy is going on with the underlying numbers.

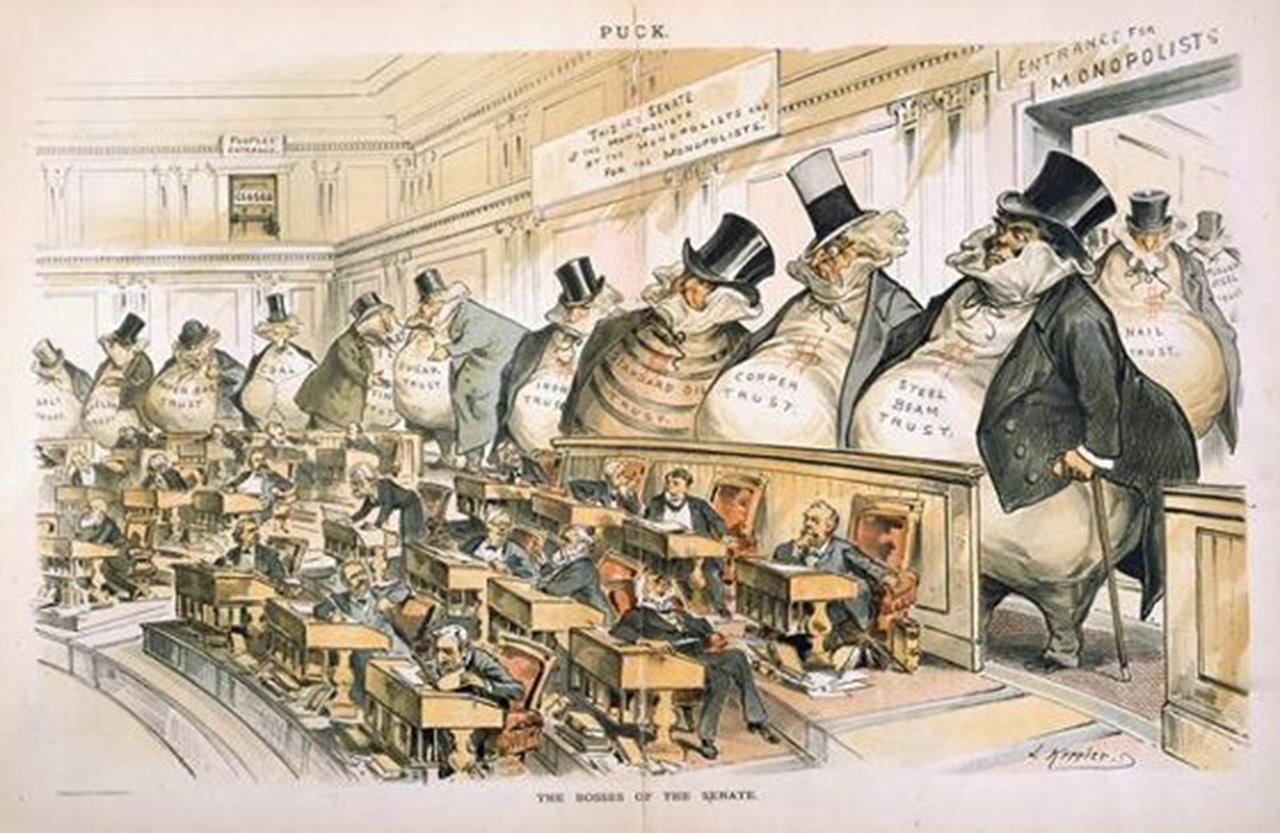

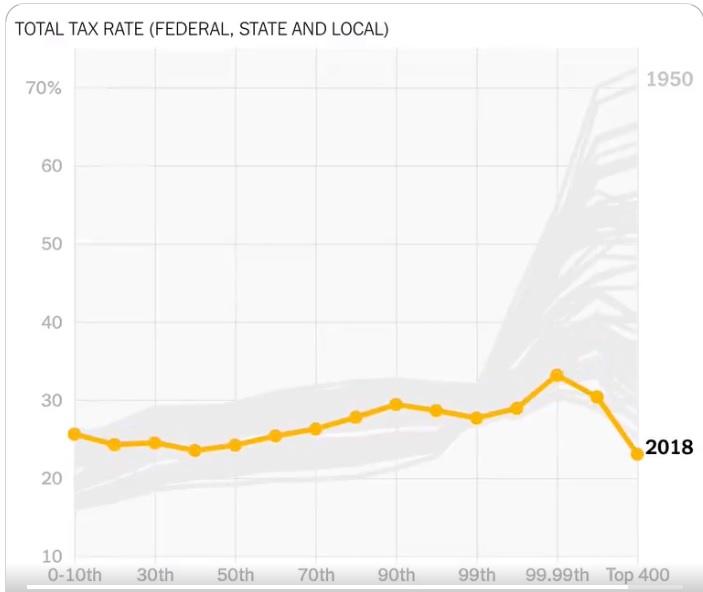

The Times’ report draws upon the work of Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, two UC-Berkeley economists who are also currently advising the Elizabeth Warren campaign for president. In their newest study, they purport to show that the overall tax burden (federal, state, and local) on the ultrarich, defined as the top 400 earners, has now fallen below the rate paid by even the poorest decile. As the chart below implies, these findings also represent a long-term regressive shift in taxation over the past 70 years.

Source: Screencap of Saez & Zucman, as relayed to the New York Times, October 7, 2019

Be skeptical of these findings though, as they are at odds with the established literature on tax progressivity in the United States.

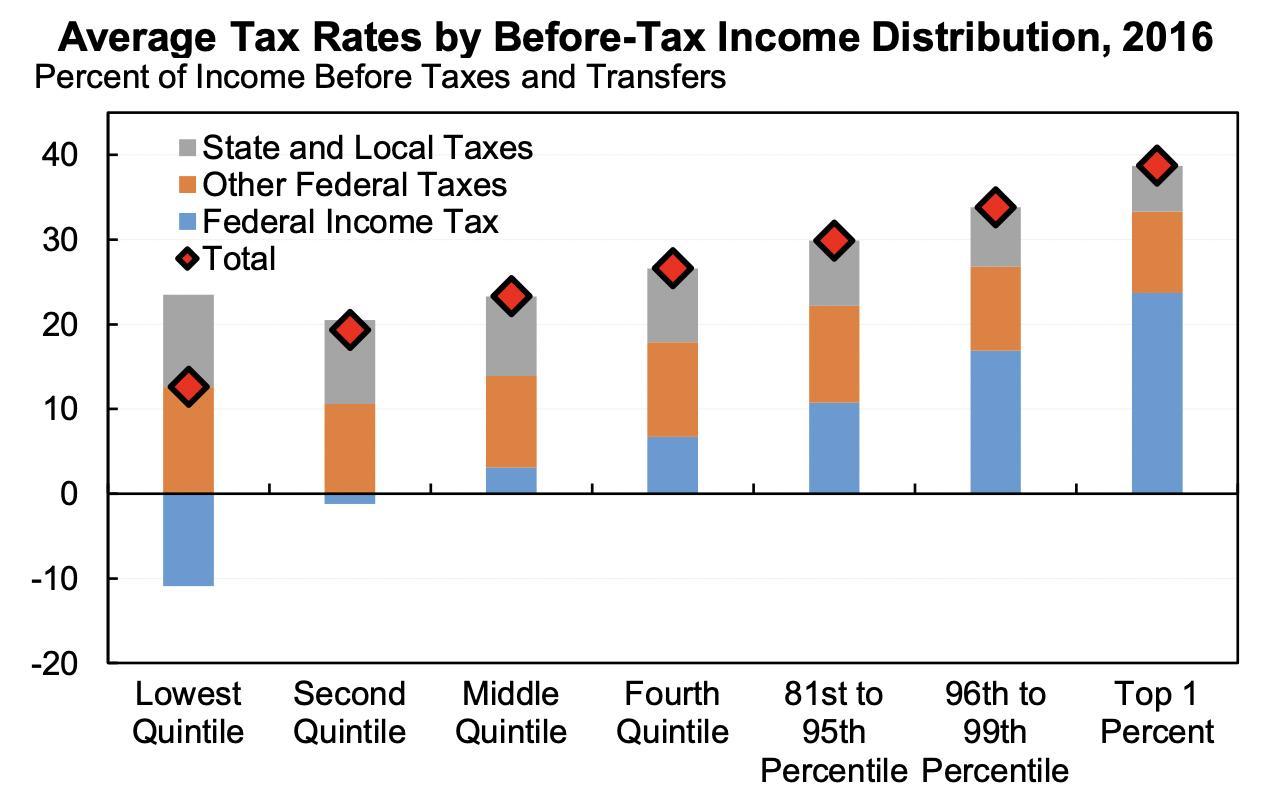

To understand how, we may begin with the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). For the past 40 years the CBO has maintained and published annual estimates of the average federal tax rate paid by each quintile of the U.S. income distribution. The CBO series only includes federal taxes (personal income, payroll, corporate, and excise), but federal taxation is the lion’s share of the overall tax burden in the United States.

The CBO’s figures diverge sharply from the findings in the New York Times report. Whereas Saez and Zucman place the top 1 percent’s total tax burden (federal, state, and local) at around 30 percent of its income in 2016 (the latest year available for comparison in both series), the CBO’s estimate for federal taxes alone is actually higher at 33.3 percent.

A similar inconsistency may be seen at the bottom of the distribution. According to the CBO, the bottom quintile (20 percent) of earners paid just 1.7 percent of their income on federal taxes. Saez and Zucman’s numbers also include state and local taxation, but their estimates for the poorest segment’s overall tax burden leap to nearly 25 percent. While state and local tax burdens do skew somewhat in a regressive direction, other data suggest this spike is entirely implausible.

The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) maintains a separate estimate of the average state and local tax burden across the income quintiles found in the CBO series. According to ITEP’s most recent numbers, the top 1 percent currently pays an effective state and local tax rate of about 7.4 percent. The bottom quintile pays about 11.4 percent. These numbers confirm the moderate regressivity of state and local taxation, but they are also far short of being able to reverse the more pronounced progressivity of federal taxation.

Jason Furman, former chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Obama, combined the CBO and ITEP estimates in response to the New York Times report. His main figure appears below, and it confirms that the overall tax distribution for the most recent available year in both series (2016) is clearly progressive. Even though state and local taxes do increase the burden on the poor, the wealthiest earners still pay a much higher tax share.

Source: Jason Furman, combining estimates from the CBO (federal) and ITEP (state and local)

So why is there such a pronounced difference between these conventional sources and the new Saez-Zucman estimate?

Bear in mind that Saez and Zucman have not yet officially released their figures or their underlying methodology. They simply gave their findings to the New York Times, which credulously reprinted them as if they were already established fact. Saez and Zucman are familiar faces in the ongoing debate over inequality, where they have produced estimates that consistently report much higher levels of income and wealth concentration than almost all other alternative measures of the same. Based on the pair’s previous track record and clear partisan connections to the Warren campaign, the Times should have exercised greater diligence before presenting their numbers as conclusive.

While we await Saez and Zucman’s full estimates, several clues have emerged that explain why their numbers are so far off from the better-established CBO and ITEP series.

First, as Zucman recently admitted on Twitter, their series removes the refundable portion of the earned income tax credit (EITC) from the bottom quintile’s federal tax burden. He claims this was done to separate the alleged “muddle” of transfer payments from the mix when looking at tax data, yet this produces highly misleading results.

The EITC is an intentional feature of the federal tax system designed to reduce its burden on the poor and provide eligible filers with an offsetting payment, thereby increasing the income tax’s overall progressivity. It is administered directly through annual tax return filings to the IRS and functions as an income-chained poverty-alleviation measure. For these reasons, the CBO incorporates the refundable EITC payment into its federal tax-distribution figures and has consistently done so over the past 40 years.

The effect of removing the EITC is not only a break from established statistical practices, it is also arguably deceptive. By excluding a key policy that enhances the progressivity of the federal tax system, Saez and Zucman end up with a distorted picture of the federal tax burdens and accompanying benefit payments to the poorest earners. This gives a false impression that the federal tax system falls more heavily on the poor than earners in the lowest quintile actually experience.

The second problem arises from Saez and Zucman’s treatment of data in the last two years. As noted, the most recent CBO release is from 2016. Yet Saez and Zucman purport to present more recent estimates, including last year.

There’s a reason why the CBO series lags in date. The IRS has yet to release its official income tax statistics for 2018, which raises the question of how Saez and Zucman are able to present estimates for a year in which we have extremely incomplete data.

As of this writing, neither economist has offered a clear answer save to note that their methods will be included in their forthcoming book release on the subject. Zucman has hinted in his comments since the Times article that their 2018 estimates work around the IRS release by using available totals of corporate tax revenue, and distributing it across the top 400 earners to get their results.

Since they didn’t provide additional details of the exact assumptions that went into the 2018 estimate, their approach seems both premature and empirically dodgy. It would likely constitute a break in their series from earlier years where better income data are available — and, conveniently enough, at the exact moment their series purports to show a regressive shift that substantially reduces the tax burden on the top 400. Furthermore, the provisions of the 2017 tax cut bill affected both the corporate and personal income tax rates, which almost certainly means some income shifting occurred between the two due to tax planning in the highest brackets. Without also knowing the as-yet-unreleased IRS income tax numbers, accounting for income shifting is likely a challenge. In short, the Saez-Zucman numbers for 2018 are almost certainly premature.

These issues leave us with a highly unconventional approach to presenting and vetting new economic data. In preparing their new numbers for the Times, Saez and Zucman appear to have eschewed best practices for estimating the distribution of tax burdens over the population as found with the CBO, which has employed the same underlying methodology since 1979. They also sidestepped the normal scholarly vetting process for new data, such as posting a working paper that details their methods and data sources.

Instead, Saez and Zucman released their new findings by providing privileged access to a friendly newspaper’s editorial page. Rather than shedding light upon important questions of scholarly inquiry, the result is a splashy story designed to capitalize on the news cycle and lend support to partisan electoral politicking. More sober analysis, rooted in established methods and publicly available sources such as the CBO and ITEP, show that story is also likely wrong.