by Guest Author

I submit to you that there is a difference between “money” and “currency.”

What is the purpose of currency? Currency is the medium by which an economy can transmit economic value between its agents and standardize the exchange of unlike items; that is, currency establishes a system that improves upon barter economics.

In its truest sense, currency is a voucher of retained economic productivity. When a person does labor that brings economic value, or transfers items of economic value, the currency they receive serves as “verification” economic contributions have been accumulated or transferred to another party.

In a barter society I till your farm for you, you provide a cottage on your land for me; my family harvests wheat and swaps it for your cheese. In an economy with currency, economic agents have the flexibility to work at a factory in Boston and exchange that labor for a car in Miami; the currency carried across state lines certifies economic contributions were indeed done at some point, and it permits the purchase of someone else’s labor in a distant location.

A barter system would permit no such transaction. The more currency one has, the more economic contributions they have retained over time, and the more economic contributions they are able to demand as a result.

If, however, currency is issued without accompanying economic contributions, what value does it have other than the paper on which it is printed? The only difference between sanctioned and counterfeit currencies is that sanctioned currencies are interpreted as having value (i.e. exists as a function of completed economic outputs), while counterfeit currencies are interpreted as circumventing industry.

The Difference

Herein lies the difference between “money” and “currency:”

- Currency standardizes the value of labor.

- Money standardizes the value of currency.

If the supply of currency grows at a rate which exceeds the growth of aggregate economic contributions, the value of economic contributions is hence diluted. That may sound backwards, so think of it in terms of an annual futures curve: If one unit of spot labor is $100, and one unit of 3-year future labor is $300, the spot labor is worth less (ignoring present value calculations). However, very few of us have the option to defer labor 3 years into the future, hence we complete labor at present compensation, in effect “selling the spot, buying the future”—a negative rolldown return.

It is for this reason currency needs a barometer by which to be standardized, and it is for this reason gold has been considered “money” since the dawn of mankind. It is scarce, has a finite supply, cannot be diluted, and the supply cannot be increased without an economic contribution of its own—exploration and mining; in a very real sense, miners could be thought of as the world’s central bank.

Limitations

There are obvious limitations to using gold in all global transactions, and currencies solve for many of these limitations. However, since currencies also lack some of the most imperative features of gold—most notably a tangible limitations on the expansion thereof—it is critically important to understand the mechanics that would keep its transmission of value as “gold-like” as possible (that is, preserving its moneyness), as well as dynamics that could lead to failure of that objective.

In a very basic sense, the most prominent risk to a currency is the risk that it no longer conveys accumulated economic value— that it really does become viewed as paper, and nothing more; interpreted differently, even the sanctioned currency becomes viewed as taking on counterfeit properties. The most straightforward way this could come about would involve insufficient oversight of currency supply management, whereby supply of currency becomes deeply disconnected from aggregate economic contributions—keeping with the earlier analogy, a currency/labor curve in parabolic contango.

The commercial and central banking systems are supposed to solve this very issue; however, whether in ignorance or arrogance, they have been criminally ineffective.

Understanding The Failures

But before we can understand its failures, we must first understand the evidence it has failed.

I believe there is no greater evidence than the existence of negative-yielding debt—particularly corporate debt.

As of this writing the amount of negative-yielding corporate debt exceeds $16 Trillion USD; to be clear, that is trillion, with a “T.” To understand just how absurd the existence of even one negative-yielding dollar is, it may be of use to rephrase “negative-yielding” into “guaranteed capital depreciation.” Guaranteed capital depreciation is only one step above guaranteed capital destruction—the assurance one’s capital will, with 100% probability, be worth nothing.

Assuming lack of violent threat, under what circumstances would one willingly accept guaranteed depreciation of capital? Well, if you wish to be technical, perhaps because there is some utility derived from its use in the interim, such as with a vehicle. Or, perhaps the destruction itself delivers some form of utility.

Or, more plausibly, perhaps the opposite action—that is, expansion of capital—fails to deliver utility.

Under what circumstances would that be the case? If there is too much of it. I submit the existence of negative-yielding corporate debt is evidence of this.

Two Examples

In behavioral finance, the Friedman-Savage double-inflection utility function describes a condition whereby investors, if they perceive their wealth to be great enough, become risk-seeking. This is known as reference-dependence. Given a capital system is the sum of all its participants, it is not unreasonable to think one may encounter a similar phenomenon at the systemic level.

One of the issues with negative-yielding corporate debt is that it egregiously violates the order of capital structure. I will outline how with two different examples:

Example 1:

When a company raises debt, they of course increase their liabilities as well as their assets. Assuming the debt is secured, lenders expect to have recourse on company assets in the event of default. For simplicity, assume a lender issues a senior zero percent, zero-coupon bond that needs to be repaid in 1 year. Of course, this bond is hence issued at par, so the company receives $100 from the lender, and they are expected to return $100 in 1 years’ time. In the event of failure to repay, the lender expects to have a 100% claim on $100 of company assets.

Now imagine the zero-coupon bond has a -2% yield. In this situation, the company would book $100 in loan proceed assets, but the note payable would be $98. The lender, in effect, has been “made whole” on $2 already, and they would hence have a 100% claim on only $98 of assets. This is essentially a condition of decaying recourse. To my knowledge, there is no such thing as a decaying-recourse clause, but even if there were should that not be reflected in the offered yield?

Example 2:

As another example, pretend Company ABC sells Lender DEF a $1MM bond at 4% interest; Company ABC now owes Lender DEF $40,000 annual interest for the privilege of using their money.

Now pretend a year later Company ABC sells another $1MM bond at 4% interest, this time to Lender XYZ. Company ABC could use the loan proceeds to pay off Lender DEF—i.e. they could refinance the loan—and they would owe XYZ $40,000 annually for the privilege of doing so. Alternatively, they could service both loans simultaneously until the maturity date, in which case they are paying both lenders $40,000 annually for the privilege of using their respective proceeds.

But consider if, instead, Company ABC sells Lender XYZ a bond yielding -4%. The -4% coupon could be used to offset the 4% cost to borrow from Lender DEF. In other words, Lender XYZ is now responsible for servicing the cash flows for Lender DEF’s loan. Moreover, the debt service on the initial loan is now default-free to DEF because the loan proceeds from XYZ were already issued and booked to ABC. In this manner, Company ABC was able to transfer debt service responsibilities to Lender XYZ, and Lender DEF was able subordinate default risk to XYZ. As described, negative yields functionally shift equity-owner responsibilities without transferring equity-owner rewards.

How Did We Get Here

These mechanics do not make any sense whatsoever, yet here we are with $16 Trillion of this. How did we get here?

As with many things, the problems start at the ground floor—in this case, the fractional-reserve banking system. When banks take in deposits they are booked as liabilities, and those liabilities have an interest rate. Banks are permitted to lend—i.e. expand the monetary base—a multiple of this liability. This is how “currency” is created.

Once currency is created, there are mainly four places it can go (read: be absorbed): Capex and business operation and investment, personal consumption and expenditures, investments in capital assets, or back to the banking system from whence it came.

The first two categories are semi-fluid, as capex and business operation expenses should result in an expansion of gainful employment, and that expansion should theoretically filter to personal consumption. This is, of course, the nature of economic cycles.

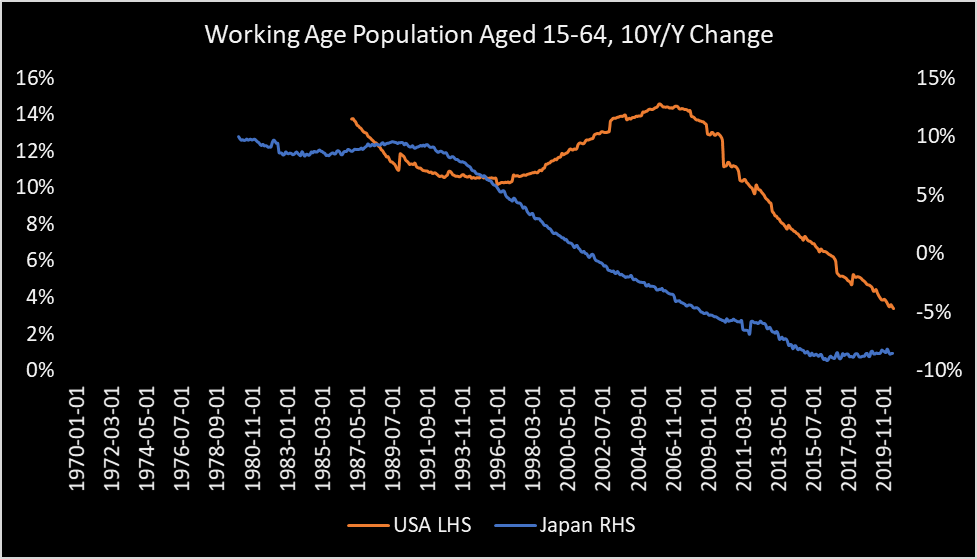

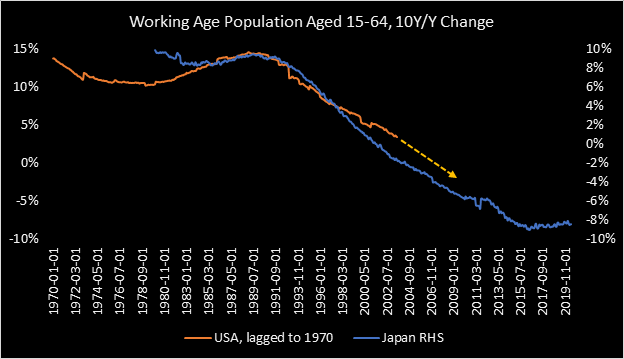

Demographics

Demographics also play a role—i.e. age demographics, working-age population, and general population growth.

Presuming there is a theoretical point at which business spending and capex are statistically considered saturated, the remaining money could be retained in non-productive assets (CASH), used to purchase marketable or real assets, or used to reduce debt. Said differently, the excess currency could be sterilized, could be used to inflate prices of a different asset, or returned to the banking system from whence it came.

Similar to what is described above, personal consumption and expenditures can also reach a saturation point. The saturation point can be augmented by increasing the size of the household, but in the absence of procreation let us assume households will spend only the amounts necessary for consumption and lifestyle maintenance, and lifestyle improvement within the tolerance of prudency.

In other words, not every family will blow through all their earnings every single week if living conditions give them a choice; they will also save some. This, too, will leave them with an excess which can be funneled to marketable or real assets, or returned to the banks from which it came.

Let us assume marketable and real assets, too, are purchased to the greatest extent prudent. Afterall, every business with a going concern knows they need to save for a rainy day, and every household knows they need to save for post-career plans. This demand for investments raises their values, increasing the worth of households and corporate entities. This must be stated explicitly for a point to be made later: this means the values of stocks, real estate, and bonds all go up. To the investor this is, of course, the expected and desired outcome.

Roundtrip

After the entire roundtrip, bank-initiated currency expansion returns to the banking system, where some of it becomes a reserve for additional monetary expansion. In other words, the banking system creates liquidity from collateral, and a fraction of that liquidity actually becomes collateral for the generation of additional liquidity. This mechanically pushes deposit rates lower (read: the liabilities get cheaper) given an interest payment on fully-circulated money is equivalent to the bank paying interest on the money it created.

This is not the only place banks reap a benefit, however. As the bank-initiated currency circulated through the system into capital assets, banks experienced a lift to their capital adequacy as bond prices went up (yields went down). In effect, fractional-reserve lending installs a feedback loop that reflexively improves the appearance of vibrancy in financial institutions; this is, however, a mirage—not because banks are in some way inherently fragile entities, but because feedback loops are inherently fragile mechanisms.

The story does not end here, however. Given economic conditions are cyclical, a point will inevitably come when economic activity grinds slower and productivity temporarily regresses. Adverse economic conditions are a hardship to the citizens, and central banks aspire to shine by saving laymen from the nuisances of economic cyclicality. In their infinite wisdom, central bankers swiftly respond by making conditions more “accommodative” through lower rates, increasing the monetary base, or both.

Not Stimulating

Going back to the earlier definition of “currency”, it should be fairly intuitive why expansion of the monetary base is not stimulating: it is the equivalent of issuing vouchers of completed economic contributions when those contributions have failed to transpire. That is, by definition, a counterfeit voucher. If Central Bankers could follow this conversation, they would argue expanding the monetary base, in effect, “pulls forward” anticipated economic contributions.

Fair enough, but that is incompatible with the notion of maintaining the “moneyness” of currency; the issuance would not vouch for completed economic activity (instead, it hopes to be validated in the future), and there is no way to guarantee the future economic growth will justify the chosen growth rate of the monetary base. For all intents and purposes, that implies insufficient oversight of monetary supply management.

Lower Interest Rates

Alternatively—or additionally—the central bank may decide to lower interest rates. Theoretically, lower costs to borrow should free up cash flow and multiply economic activity. This is empirically false— or at the least it is not ubiquitously true— but let us ignore that for now. In fact, let us assume it may be true more often than not. If the central bank lowers rates they generate two second-order effects:

The first is that freeing up cash flow, all else held constant from 8 paragraphs ago, frees up the amount that eventually returns to the banking system. This in of itself is not inherently nefarious, but it creates conditions that support continued dilution of the currency/labor exchange rate; in other words, it frees up even more liquidity to return to the banking system and become collateral for even more monetary expansion. This innately dilutes the ratio of economic contributions to vouchers of completion (currency).

Second, before the freed-up cash flow can recycle to the banking system, it must first progress through the cycle mentioned earlier: capex and business operation and investment, personal consumption and expenditures, and marketable and real asset investment. This naturally pushes prices higher, and that is both the expected and desired outcome (the central bank mandate is, after all, to hit an inflation target.) Bonds are not exempt from this dynamic, and they too will go up in price.

Simplifying Assumptions

In the interest of time and space I will do a thing I prefer to do as little as possible: I must make simplifying assumptions. Let us assume the aforementioned processes repeat over and over, for decades and decades. It should be fairly intuitive how the feedback loop would continue to endorse monetary expansion, but what goes unnoticed is how the rate of expansion would change over time.

After many iterations of the described cycle, the amount of “excess money” created with each iteration will actually increase; in other words, less currency will go towards certifying economic productivity, and more will go towards consumption or asset inflation. The reasons are quite intuitive: there is simply an upper limit to growth and consumption. Companies can only grow so large, there is only so much infrastructure, there are only so many customers, there is only so much market share, etc. Perhaps the terms “diminishing marginal productivity” or “diminishing returns to scale” rings a bell.

Increasing the labor force—i.e. population—would be a perfectly adequate mitigating factor, as it would amplify the aggregate “currency absorption mechanisms”, but it appears the babies have gone on strike:

Source: Created by author using data from fred.stlouisfed.org

And for some additional perspective:

Source: Created by author using data from fred.stlouisfed.org

Furthermore, if a person is faced with conditions whereby they cannot work anymore than they already do, and they have purchased everything they want or need, the natural thing to do is allocate their excess currencies (read: retained economic contributions) toward capital assets. Compounding returns, after all, may exhibit diminishing marginal utility, but they do not exhibit diminishing returns to scale. In fact, it is quite the opposite. Ergo, with more excess to disperse, more inflation will be delivered to asset prices. All asset prices.

Consequences

Again, this is the expected and desired consequence—or so one thinks. You see, stocks, real estate, precious metals, collectibles, and just about every other major asset class have subjective valuations and heterogenous supply-demand function. The value placed on a given equity will depend on the growth and cash flow assumptions of the analyst; real estate will depend on demographics, replacement costs, and utility of residence; collectibles are a thinly-traded market with subjective price determinants.

But bonds? Bonds are an instrument of truth. Bonds have an objective pricing mechanism whereby one can know, absent default, the exact ex-ante return they will receive when held to maturity. In fact, for this reason it is possible to objectively determine if a bond is too cheap or too expensive, no assumptions needed. In fact, bonds are the only instrument that I am aware of that can definitively tell you, on an ex-ante basis, if the realized return will be negative.

Reread that statement, and understand I am not referring to negative expected future return. I am talking about the known realized return at the time of purchase. No other instrument can do this.

There is a popular narrative that stocks are priced correctly today because of how low bond yields are—either by comparing corporate equity D/P or E/P to bond yields, or using low government bond yields as an excuse to justify paltry discount rates. However, I believe this is a fundamental misinterpretation of what the bond market is saying. I have already outlined the absurdity of negative yields and why there is no reason those conditions should exist, yet those conditions do exist.

I also explained the circumstances that would propagate those conditions; based on the feedback loop I have outlined here, the most plausible of those three catalysts is the existence of too much currency.

Low Rates Don’t Justify High Prices

So, perhaps it is not correct to infer higher stock prices are justified as a function of low bond yields; perhaps everything is too expensive, and bonds are the only instrument capable of objectively and unambiguously transmitting that message.

That description sounds a lot like “the everything bubble”, which, while not inaccurate, is a term that tends to get ridiculed and dismissed as doom and gloom nonsense. And while it may be true if everything is too expensive everything is in a bubble, the bigger issue is the subtle rupture of monetary credibility.

You see, all things are an exchange rate– my labor for your cottage, my family’s grain for your cheese, my work at the factory in Boston for “their” currency and “their” currency for your automobile in Miami. If inflation of the currency base has failed to generate a proportionate impulse of economic output, the exchange rate of currency to retained economic contributions has been egregiously impaired; that is to say, currency has failed to retain its “moneyness”. By definition, a sanctioned currency fitting this description is no different than a valueless counterfeit.

Conclusion

Negative nominal yields do not imply negative inflation expectations, and negative yields do not imply your stocks are worth more. Sadly, negative yields imply your stocks are worthless.

What is the takeaway? I continue to remain bullish on precious metals, precious metal miners, and commodities. That is not to say I expect immediate, spectacular results, and that is not to say the “exchange rate” of Currency/Gold, Currency/Commodities, or Currency/Miners will not turn unfavorable in the short term.

However, looking out over a three-to-five year horizon, I expect those assets will reflect the conditions of currency dilution we have experienced and will continue to experience. I also think this is an excellent time to be short investment-grade corporate credit, as the medium-to-long term downside outweighs the upside in my view.

Author

Blackbeard Research is an independent investment professional with over 11 years of experience. My investment philosophy could be described as a benchmark-agnostic, hybrid global macro approach with a value investing bias. Research topics focus primarily on market and macro events I feel are misunderstood or underappreciated.