Holy cow, Los Angeles. The economy is gradually opening up. But the exodus has started hard and heavy. And the influx has stopped.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

A little anecdotal thingy before we get into the horrifying data: I was on a call with a guy from Google – they want my WOLF STREET media mogul empire to spend money advertising on Google. He was working from home, and since he no longer has to go to Google’s office in Redwood City, he moved home to his parents in St. Louis, Missouri. One more soul gone from the Bay Area housing market, and he still has a job.

Coastal California is an expensive place, and if you lose your job, and you’re not rich, and maybe your stock options didn’t pan out, why stick it out? And if you can work from home, why spend a fortune on housing when you can spend a lot less elsewhere? These are the questions bedeviling millions of workers and former workers.

A housing market as inflated as California’s needs a constant influx of people to keep it going. And when people leave – either because their jobs have evaporated or because they can do their work-from-home somewhere else – well, then the housing markets, both renting and buying, head into trouble.

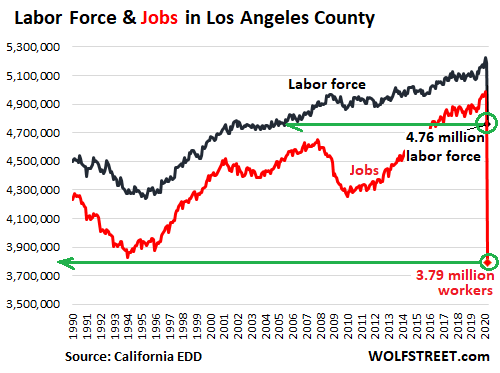

In Los Angeles County – with a population of 10 million – jobs fell off a cliff. This is where California’s largest and most intense outbreak of Covid-19 was threatening to spiral out of control, New-York-City-like. A lockdown and social distancing brought it under control and prevented a New-York-City-like tragedy. But the job market imploded.

The number of working people collapsed by 23%, or by 1.16 million people, counting from December last year, to just 3.79 million workers, the lowest number in the data series going back to 1990.

Until today, the lowest number of workers in the data series – released today by California’s Employment Development Department – was 3.83 million in January 1994, during Southern California’s Aerospace Crisis. Until today, the lowest this century was in January 2010, during the Financial Crisis, with 4.26 million workers. Back in December, there were still 4.95 million workers.

The labor force – and that’s particularly important for the housing market – plunged by 8.3%, or by nearly 400,000 people, to 4.76 million people, the lowest since 2003. The labor force plunged because people left the county, retired, or stopped looking for work. The unemployment rate shot up to 20%.

The chart shows the labor force (black line) and working people (red line). Note the Aerospace Crisis, the Dotcom Bust, and the Financial Crisis. In the prior downturns, the labor force only seriously shrank during the Aerospace Crisis, dropping by 480,000 people over a four-year period. During the Dotcom Bust and the Financial Crisis, there were some wobbles and dips, but no wholesale shrinkage in the labor force (the straight vertical red and black lines on the right are not the frame of the chart but the data lines):

Bay Area hit catastrophically, but less catastrophically than Los Angeles.

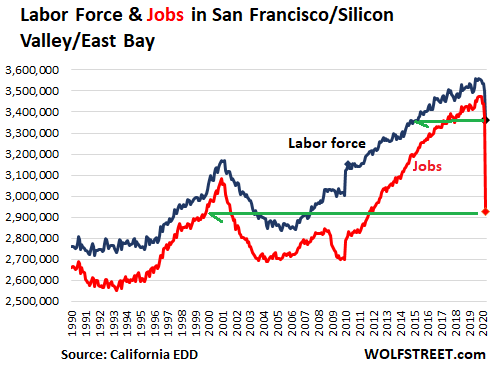

San Francisco, Silicon Valley (the counties of San Mateo and Santa Clara), and the East Bay (the counties of Alameda and Contra Costa) are the biggest drivers of employment in the Bay Area. Together, they’re somewhat smaller than Los Angeles County. They’re fused, with many people living in one county and working in another county.

The number of working people in those five counties combined (red line in the chart below) plunged by 13%, or by 545,000 people, to 2.93 million, taking it back to November 1999. It was the largest plunge in the data. The chart below shows the Dotcom Bubble and Bust, compared to which the Financial Crisis was puny. Then came the epic boom of the Everything Bubble, and now the most epic bust.

The labor force (black line) plunged by 192,000 people to 3.36 million, the lowest since August 2014. But labor force movements are slower than changes in jobs. During the Financial Crisis, the labor force barely dipped. During the Dotcom Bust, the labor force continued to drop for two more years after jobs had started to stabilize and tick up again:

Clearly and hopefully, many of these people that have been laid off will get their jobs back. But many won’t. The uncertainty is huge. The entire startup field has been disrupted. That started early last year, and has continued to get worse, with numerous layoffs and shutdowns taking place throughout last year and into this year. Then came Covid. No one knows for sure what’s left over once the dust settles. Many of these jobs will be gone permanently.

In the Bay Area, Big Tech has largely switched to work from home, and their employees have jobs, but it doesn’t matter where they do those jobs, and the exodus, particularly among the younger workers – like my counterpart at Google – has begun there too.

Other people who have been laid off cannot afford to live in the Bay Area for long. For them, the state unemployment compensation and the federal Pandemic Unemployment Assistance help but are not enough to fund the high costs of living. If they haven’t already left, and if they don’t get jobs soon, they will leave. This is precisely what happened during the Dotcom Bust. But it wasn’t all at once. It took years to play out. The average rent dropped 25% during those four years.

Mortgage forbearance and the refusal to pay rent – with evictions on hold – will slow down the process. People can stick it out as long as they don’t have to pay for housing. But this is not a permanent feature. And then the floodgates open.

And there is another driver of the housing market that has evaporated: The influx of people from other countries – in the Bay Area, that’s largely educated people from Asia – has stopped cold.

No one knows how all this will shake out, how many companies will survive this, and how many people they will retain, and how many of those people they retain can work from anywhere, even from St. Louis, and they don’t have to rent or buy a home in the Bay Area.

This will take a long time to sort out and get through – countable in years. The startup shakeout was already underway for a year before Covid had arrived on the scene, but Covid compressed this dynamic into the shortest possible amount of time.

This labor force and jobs data is based on household surveys collected by the Census Bureau in the middle of April. The next set, collected in mid-May to be released a month from now, will likely be even worse. But hopefully, it will stop getting worse after that.

California’s economy is now gradually opening up – the businesses that are still around to open up. Big Tech has continued to work throughout, shifting work to home. What’s left of the startups remains a mystery. Uber, a large employer in the Bay Area, has gone through round after round of layoffs before Covid and doubled down after Covid. Macy’s shut down its tech center in San Francisco early this year before Covid became an issue, and laid off 1,000 people. Charles Schwab announced last November to move its headquarters from San Francisco to Texas. This has been a litany for a while. But the turmoil now is cleaning house.