A curious phenomenon.

By Nick Corbishley, for WOLF STREET:

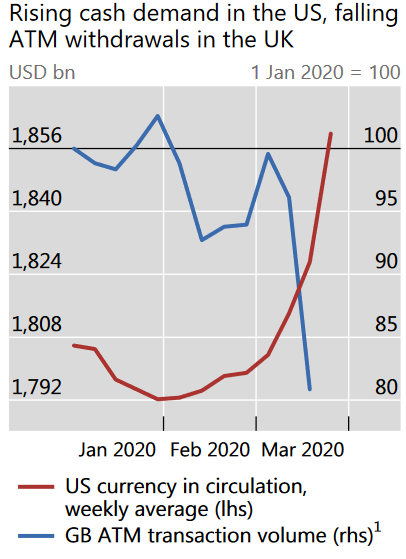

In the United States, as coronavirus concerns grew and state after state went into lockdown, and as consumption plunged and unemployment exploded at a previously unimaginable rate, the amount of physical dollars in circulation spiked to $1.89 trillion, as of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet on April 16, having jumped 9.1% compared to a year earlier.

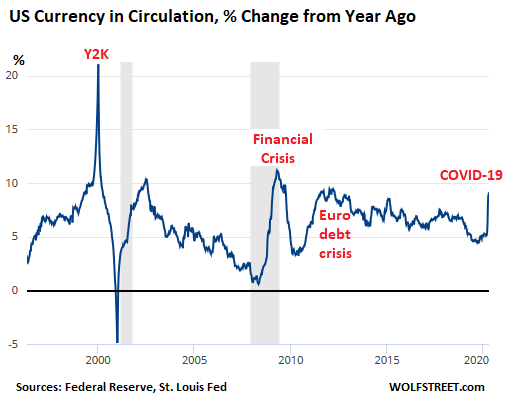

During the darkest days of the Financial Crisis, the demand for U.S. dollar banknotes spiked at year-over-year rates of over 8% for ten straight months and peaked at rate of 11%. But that was nothing compared to what happened during the Y2K craze, when fears that computer systems would malfunction when dates rolled over in the new millennium triggered a mad rush for US dollar banknotes. In December 1999 the total value of dollar bills in circulation spiked by 16.9% from a year earlier, the highest rate since the war-years of the 1940s:

The total value of euro banknotes in circulation in March, as countries across the Eurozone went into Covid-19 triggered lockdowns, increased by €36 billion from February, to €1.31 trillion, according to the ECB. It was the fastest monthly increase since October 2008. And it was up 8.1% from a year earlier. This all happened as consumption in the region slumped to unprecedented levels.

Bank notes denominated in US dollars and euros, the two biggest global reserve currencies, are stashed away in large quantities in other countries with unstable currencies, and they’re used to trade certain types or merchandise on the global black market. The euro is also used as currency in some areas that are not part of the Eurozone. And the dollar is used actively in countries that are either fully or partially dollarized. The Fed has estimated that around 70% of 100 dollar bills, which account for nearly 80% of the total value of U.S. currency, are held abroad.

But what triggered this spike wasn’t sudden demand overseas. The banking system must be able to provide sufficient currency even during spikes in demand at local ATMs and bank branches, and a sudden spike like this is a sign that local people are hoarding cash during times of uncertainty — with empty shelves at supermarkets having spooked people.

What makes the current dash for dollar and euro banknotes particularly interesting is that it is happening at the same time that the use of cash around the world is being heavily demonized for increasing the risk of Covid-19 infection. In early March, in response to a question about whether banknotes could spread the coronavirus, a WHO spokesperson said: “Yes it’s possible and it’s a good question. We know that money changes hands frequently and can pick up all sorts of bacteria and viruses … when possible it’s a good idea to use contactless payments.”

Around the world, media outlets and long-standing enemies of cash such as credit card companies and fintech start-ups seized on the WHO’s comments and magnified them, sparking fears over the safety of cash.

The WHO has since walked back its comments, arguing that it was not advocating for people to abandon the use of cash but rather that they should wash their hands after handling it, especially before handling or eating food. Central banks have also come out in force to try to dampen public fears about using cash.

But the damage may have already been done. In a report published last week, the Bank for International Settlements noted that “irrespective of whether concerns are justified or not, perceptions that cash could spread pathogens may change payment behaviour by users and firms.” Even in a traditionally cash-loving country like Spain, many retailers are urging people to use other payment methods.

In the UK, where the use of cashless payment cards was already rampant long before the virus crisis began, cash withdrawals at ATMs have fallen sharply in recent weeks (chart via BIS):

Central banks in the U.S., China, South Korea, Hungary, Kuwait and other countries have even begun “quarantining” or sterilizing banknotes, to ensure that cash leaving central bank currency centers does not carry pathogens. All of this is happening despite the fact that many digital payment methods that are being touted as safer, healthier alternatives to cash are just as likely, if not more so, to spread infection.

As the BIS notes, debit and credit card transactions generally require a signature or a PIN entry at a merchant-owned device for larger transactions. Given that the virus survives best on non-porous materials such as plastic or stainless steel, debit or credit card terminals or PIN pads could prove to be even worse vectors of the virus. To reduce that risk, authorities, banks and card networks in countries such as Austria, Germany, the Netherlands and the UK have set higher transaction limits for contactless payments.

The more that consumers get accustomed to the ease, convenience, and relative safety of contactless payment methods, the less likely they are to return to physical cash in the future. At least that’s what credit card companies, banks, tech giants and fintech startups are hoping. The BIS report concludes that the Covid-19 outbreak could lead to “both higher precautionary holdings” (i.e. hoarding) of cash by consumers and “a structural increase in the use of mobile, card and online payments.” By Nick Corbishley, for WOLF STREET.