Necessity is a magnet, and perhaps as what’s essential in our lives changes, social capital will start sprouting, even in the most unlikely places.

“Desert” has become a favored metaphor: food deserts describe neighborhoods with few places to buy fresh fruits and vegetables, democracy deserts describe political regions rigged by gerrymandering, and so on.

Many of us working our way forward to a more resilient, sustainable and healthier future talk about social capital–the intangible but very real network of connections and relationships that characterize social mammals such as humans.

We call this network of ties and trust “capital” because it takes time and effort to build and maintain, and it generates value.

The value generated by social capital has many forms, but the one most commonly cited is favors with an economic value. We say we’re “calling in favors” when we seek help in locating clients, contractors, mechanics, employees, etc., or ask for help in childcare, yardwork, picking someone up at the airport, etc.

The foundations of this form of social capital are 1) longstanding ties to families, schools, home towns or neighborhoods, etc., and 2) reciprocity, being generous with one’s connections, time, experience and expertise to one’s network.

This “investment” isn’t made with calculated returns in mind (though some people do offer help in the hopes of gaining something of far more value than they offered); the eventual value generated is unknown, but everything that’s given–especially the trust that you do what you say you’ll do– is like a savings account that adds value to your place in the network.

Put more bluntly, an unreliable person isn’t going to be valued as highly as a person who commits to a task and unfailingly gets it done on time and with minimal fuss / hassle.

Unlike other forms of capital, social capital doesn’t necessarily decay over time: long-dormant connections and favors can come alive in moments of necessity.

In China and other Asian nations, much of what is automatically labeled corruption in the West is in many cases better understood as social capital bleeding into the immense financial wealth generated by state-finance connections in Asian economies.

The old school/university or home-town ties that grease deals between politicians and developers is known as guanxi in Mandarin Chinese, a word that embodies a complex web of obligations, reciprocity, trust and value that are universal characteristics of human sociability and social capital.

Ancient trading networks stretching from the Roman Empire to India were built on networks of trusted contacts in Rome, Egypt (the entrepot of trade from Mediterranean ports to the Arabian Sea ports) and India. This wasn’t corruption, it was simply business–often based on family and near-family connections.

It’s long been observed that societies with low trust in strangers–that is, low levels of trust in the fairness and reach of the society’s legal, financial and political institutions–are economically stagnant, as enterprises cannot expand beyond the trusted network of families and family-like connections.

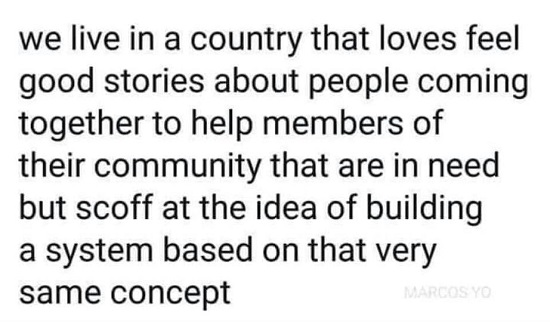

In modern industrial societies, social capital has lost value as people have come to rely on government and institutions for income, food, aid, child and elderly care, etc.–the resources and services that we once relied on social capital networks to provide.

Urban life tends to degrade social capital, which requires time, effort and caring that are often scarce in busy, over-committed lives. The frenetic pace limits the rewards of investing in social capital networks, as does the fast-revolving door of neighborhoods and workplaces: it’s difficult to establish friendships and meaningful ties when everyone is pressed for time and people move on in a few months or years.

Investing in people who are gone in a few months yields very little, so social capital dwindles to near-zero. Many urban dwellers don’t have any contact with their neighbors and only limited contact with people they work with.

The ties that exist are too contingent and weak to support much in the way of trust, reciprocity, sharing, obligation, etc.

In economic terms, if the government provides income and Corporate America provides the goods and services, the traditional need for social capital evaporates.

Humans are not just rational economic robots, and so the impoverishment of social capital deserts in which few know their neighbors, share anything with others, owe anything to anyone or trust anyone is also a desert of emotional well-being.

This has spawned a number of seminal books such as The Lonely Crowd: A Study of the Changing American Character, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community and The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in An Age of Diminishing Expectations, in which author Christopher Lasch sets aside the psychological definition of an individual’s narcissism (hedonistic egoism) to examine what he called “pathological narcissism.”

In my view, this systemic narcissism resulting from two dynamics:

1) Work/career demands so much of individuals now that they have little time or energy to build or maintain social capital networks.

2) Given the general dependence on the Savior State and corporations for life’s necessities, there is little motivation or need to maintain social capital beyond the immediate family circle.

In other words, the individual has no economic need to invest in social capital because all the essentials are provided by the state and corporations.

In traditional economies, producing goods and services in the home and sharing with a social network were essential to survival; there was no Savior State providing money to buy everything.

As for the emotional well-being value of social capital, the simulacra of social media and brand-identity fill the void, however imperfectly.

In my own experience, social capital develops organically and without extraordinary effort in the close-knit connections of shared community, family ties, faith, purpose and values. Some enterprises can foster social capital, but the demands to maximize profits every quarter make enterprises poor soil in which to grow social capital.

In an economy that optimizes time spent earning money and buying everything, very few people have much to share: they have very little free time, their career demands maintaining specialty skills over activities that generate surplus goods (hobbies, crafts, gardens, etc.) and the financial pressures to maximize income set the goals of life.

In other words, social capital deserts don’t just lack trust and connections; they lack tradable goods and services that have value in a society in which everything is store-bought.

For example, people who don’t have time or interest in preparing meals with raw ingedients will not value gifts of home-grown fresh fruit and vegetables, and so one of the fundamental forms of reciprocity throughout human history–exchanging home-grown food–has little value.

Which brings us to the last redoubt of social capital, family networks. These too have frayed as people have lost connections to any “home” locale and moved far from each other. Since there is no need for social capital to meet most of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, there is very little “necessity” glue to bind people together.

In Hawaii, the need to maintain home gardens and social capital has 100-year old roots in plantation communities in which the workers weren’t paid enough to buy everything they needed. Home gardens weren’t a luxury, they were essential because what little money that was available was needed to buy staples such as flour and rice.

Children went barefoot because there was no money for shoes or other “luxuries.”

What’s changed is what is essential. In today’s world, earning enough income to buy everything is what’s essential, and social capital is non-essential. In living memory, social capital and home food production were essential, ashaving enough money to buy everything was out of reach for the vast majority of households.

Social capital can’t be bought, it takes significant, sustained investments of time, energy and caring. In a society obsessed with financial measures of value, it’s little wonder social capital has atrophied to the point that it is a non-factor in many lives.

The value isn’t in being willing to accept something of value, it’s in creating and sharing something of value without calculating a financial return. The return isn’t financial, it’s far more valuable than that.

It’s an open question as to whether social capital deserts can be made to bloom. The soil may lack the requisite nutrients. For households hungry for sociability and social capital, it may be easier to move somewhere with fertile soil rather than to try to turn hardpan into a verdant garden.

That changes if a self-sustaining, self-organizing, like-minded group assembles around a value-purpose driven project. But that’s asking a lot of people stretched for time and energy, and of people like me who are joiners, not founders or leaders.

Necessity is a magnet, and perhaps as what’s essential in our lives changes, social capital will start sprouting, even in the most unlikely places.

This essay was first published as a weekly Musings Report sent exclusively to subscribers and patrons at the $5/month ($54/year) and higher level. Thank you, patrons and subscribers, for supporting my work and free website.