Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, http://www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

Kudos to the private equity firm. These things don’t happen overnight for companies. They happen overnight only for investors.

Golden Gate Capital – the private equity firm now infamous for asset-stripping its portfolio company Payless ShoeSource into bankruptcy and liquidation – strikes again with another of its portfolio companies, Clover Technologies, whose $693-million leveraged loan has suddenly gone to heck.

Slices of that leveraged loan are traded like securities. But because leveraged loans are loans, not securities, the SEC doesn’t regulate them. No one regulates them, though the Fed wrings its hands about them periodically. And there are $1.3 trillion of them.

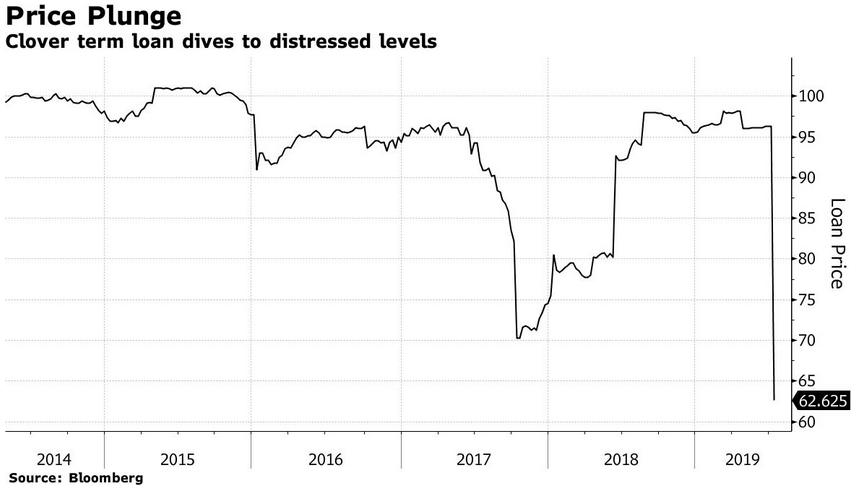

The market for them is very illiquid, even during good times, and before Clover disclosed some issues on July 9, the loan still traded at 97 cents on the dollar, according to Bloomberg. This was the day investors, such as leveraged loan mutual funds and institutional investors that held these slices, suddenly woke up with the foul odor of debt restructuring and bankruptcy in the air. Within just a few days, the price of the loan plunged 35% to 62.625 cents on the dollar.

The loan was “covenant-lite,” giving fewer protections to investors and allowing the company and its owners to get away with all kinds of things. This included the absence of certain disclosure requirements.

Not that we feel sorry for investors that suddenly got whacked: They knew that leverage loans are risky, that they’re issued by junk-rated over-leveraged companies with iffy cash-flows, often to fund their own leveraged buyout by a PE firm, and to fund special dividends back to the PE firm. Both factors apply to Clover’s leveraged loan. Investors don’t care. They’re chasing yield no matter what the risks, in a world where yield has been repressed by central-bank policies.

These slices are not liquid and they take a long time to trade, and trading is thin even in good times. But when investors want to unload, there are suddenly no buyers and the price just collapses (chart via Bloomberg, click to enlarge):

Clover Technologies, founded in 1996, is “the world’s largest collector and recycler of imaging supplies,” it says on its website, such as printer cartridges. It also recycles and refurbishes smartphones in facilities in the US, Mexico, Europe, and Asia for wireless carriers that then resell the refurbished phones to their customers.

So on July 9, Clover’s parent, 4L Holdings, disclosed to investors that Clover was losing two big unnamed customers. One was in its printer cartridge business. The other was a wireless carrier that was buying Clover’s refurbished smartphones, but has “decided to fulfill requirements for refurbished older units by purchasing them directly from the OEM,” such as Apple or Samsung. That customer remained unnamed, but “people” told the Wall Street Journal that it was AT&T.

In its disclosure to creditors, the company said that it had hired restructuring advisors, which is often an indication of a pending debt restructuring or bankruptcy filing. It invited creditors to organize and hire their own advisers. And it proposed a meeting for the week of July 22.

This was the moment investors woke up. When investors tried to sell their slices of the loan, they found that buyers at these prices had evaporated, and to sell the loan at all, they would have to take a big haircut.

When a highly leveraged company in an already tough business is threatened with the loss of revenues, there is no margin for error, as cash flow needed to service that debt can just dry up, and the results can be catastrophic for investors.

And even if the company can muddle through, at some point the debt matures and has to be refinanced, and when no new investors can be found to bail out the old investors, it’s over. This is what Clover is facing.

The $700 million leveraged loan is coming due in May 2020. Clover tried to refinance it last May, when it might have already known about the potential loss of customers, but had not yet disclosed it to investors.

It offered a juicy yield of nearly 9%, but investors balked and wanted a better price (higher yield), “people said,” according to the Wall Street Journal. Now, after the disclosures of the loss of customers, refinancing the loan is off the table altogether.

But Golden Gate, which had acquired Clover in a leveraged buyout in 2010, wasn’t shy about stripping assets out of Clover via $278 million in special dividends it extracted, according to Bloomberg: $100 million in 2013 and another $178 million in 2014.

That $178 million dividend was funded at the time by Clover issuing a new leveraged loan, the current one, whose proceeds were also used to pay off the prior loan (new investors bailing out old investors) and to fund an acquisition.

Golden Gate got its money out. Clover had more debt. Old creditors were bailed out by new creditors. The banks arranging the leveraged loan made a ton in fees. And everyone was happy. But now these new creditors – which include unwitting investors in those funds – ended up holding the bag.

On July 11, Moody’s chimed in with a devastating three-notch one-fell-swoop downgrade, to Caa3, just a couple of notches above default (here’s my plain-English cheat-sheet for the corporate credit rating scales by Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch).

“The downgrade reflects the likelihood of a default is high given the recent downward revision in earnings guidance following the loss of business and pricing pressure in both the imaging and wireless segments combined with the maturity of the first lien term loan in May 2020 that will put pressure on the business,” Moody’s said.

“The company’s hiring of restructuring advisors, request to meet with lenders in a few weeks, and challenges refinancing the term loan indicate a restructuring will occur soon,” Moody’s said.

“We also remain concerned about the longer-term business viability as a result of more limited visibility into forward financial performance and related uncertainties given the unexpected operating developments,” Moody’s said.

The near-default Caa3 rating reflects “the high balance sheet restructuring risk” along with the “near-term debt maturities,” and “the ongoing business and execution risk as management evaluates its strategic options,” Moody’s said.

These things don’t happen overnight for companies. They happen overnight only for investors.

The company had already suffered revenue declines and pricing pressures in its major businesses, according to Moody’s. Clover is also heavily dependent on just a few big customers, two of which are now leaving.

The secular downtrend in the printing sector and the competitive challenges in the smartphone-refurbishment sector, along with Clover’s high customer concentration were known to investors, but given the glory times we’re in, fundamentals no longer matter – until they suddenly do.

Moody’s also lambasted the company’s “aggressive financial policies, evidenced by its private equity ownership and history of shareholder distributions and large debt-funded acquisitions” — a reference to Golden Gate Capital.

Moody’s slash-and-burn downgrade, and the subsequent plunge of the loan deeper into distressed territory turned more institutional investors into forced sellers as they’re limited to what extent they can hold distressed debt. But it’s no biggie. It’s just other people’s money. And that loan is now a plaything for hedge funds specializing in distressed debt, and they’re hoping to make a killing. However this turns out, kudos to Golden Gate. They’ve done it again.