This article was written by Wolf Richter and originally published at Wolf Street

This came packaged into the middle of a speech by Federal Reserve Board Governor Lael Brainard, on “How Does Monetary Policy Affect Your Community?” It was under the subheading, “Some Issues to Explore.” And it would be a huge shift in how the next crisis will be handled.

During the next crisis when short-term interest rates are already at zero – for the Fed, that is still the lower bound – the Fed might not do the type of QE it did during and after the Financial Crisis when it set a target to buy a fixed amount of securities every month.

Instead, during the next crisis, when 0% short-term interest rates are no longer enough to stimulate the economy, the Fed might announce a target for slightly longer-dated interest rates, such as one-year rates, Brainard said. And it would buy just enough securities with those maturities, to bring the one-year yield down to the target range. And if more stimulus is needed, it might target two-year rates, she said:

Under this policy, the Federal Reserve would stand ready to use its balance sheet to hit the targeted interest rate, but unlike the asset purchases that were undertaken in the recent recession, there would be no specific commitments with regard to purchases of Treasury securities.

“Such an approach could help communicate publicly how long the Federal Reserve is planning to keep rates low,” she added.

It’s an “interest-rate peg”: been there, done that.

The Fed would announce that it wants the one-year yield to be at 1%, for example, and if the Fed is credible in its announcement, it might not have to buy many securities to get the one-year yield to target.

This was just one of the “ideas,” Brainard said, and “there may be other good ideas, and part of the process we are engaged in involves looking around for other ideas.” Nevertheless, the trial balloon is floating.

The Fed already implemented a rate peg before – to help provide cheap financing for the US war effort during World War II. The Fed recounts that episode:

The interest-rate peg became effective in July 1942 and lasted through June 1947. The Reserve Banks reduced their discount rate to 1 percent and created a preferential rate of one-half percent for loans secured by short-term government obligations, substantially below the 3 to 7 percent that had been common during the 1920s.

The Bank of Japan has a rate peg.

In many of the central-bank strategies to control or manipulate markets directly or indirectly, the Bank of Japan has been out on the forefront. The BOJ has been doing QE – though it didn’t call it that – long before the Fed kicked off its QE in late 2008. Then in 2016, the BOJ started its program of yield-curve targeting, which it monikered “yield curve control,” a program by which it tries to control the entire yield curve including 10-year yields.

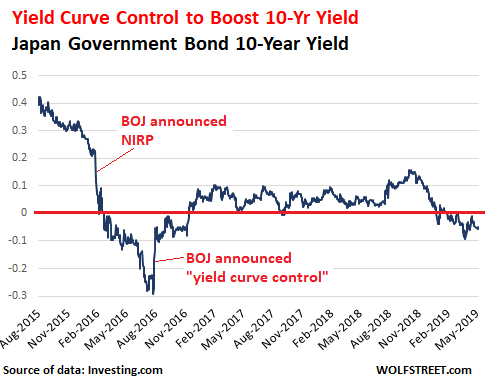

The Japanese yield curve became an issue in late December 2015 when the 10-year yield started tumbling on rumors that the BOJ would implement a negative-interest-rate policy. In February 2016, when the BOJ confirmed the rumors and announced its NIRP policy, the 10-year yield plunged further, broke through the zero line, and turned negative. And the already languishing Japanese banks were squealing.

In late July 2016, by which time the 10-year yield had dropped to -0.29%, the BOJ announced its program of “yield curve control”: it wanted the 10-year yield to be near but above 0%. The 10-year yield spiked from -0.29% to -0.08% and continued to head higher until it was above 0%. The BOJ accomplished this mostly by jawboning but also by carefully not-buying or perhaps even selling some long-dated securities. It was the reverse of the Fed’s Operation Twist.

This worked without drama until late 2018, when the BOJ – motivated by trade tensions, the global downturn in manufacturing, and the Fed’s “patience” – allowed the 10-year yield to drift slightly into the negative (data via Investing.com):

A rate peg has an “automatic exit”: Bernanke

There have been voices that have discussed a rate peg as an option, including Ben Bernanke in March 2016, after he was no longer Fed chairmen:

To illustrate how a peg could work, suppose that the overnight interest rate were at zero and the two-year Treasury rate were at 2 percent. The Fed could announce that it intends to hold the two-year rate at one percent or less and enforce this ceiling by standing ready to buy any Treasury security maturing up to two years at a price that corresponds to a return of one percent.

Since the price of a bond is inversely related to its yield, the Fed would effectively be offering to pay more than the initial market value. Think of it as price support for two-year government debt.

Timing details are important. Suppose the Fed announces on May 1, 2020 that it stands ready to buy any Treasury security that matures on May 1, 2022 or earlier at fixed prices corresponding to a yield of one percent. Note that, as time passes, the May 1, 2022, terminal date would not change (unless explicitly extended); thus, the maturities of the securities the Fed is committed to buy would decline over time, and the program would automatically end on the specified terminal date.

And here Bernanke explains how this form of QE would unwind automatically:

Moreover, any securities that the Fed bought under the program would mature by the terminal date, leaving no lasting effect on the Fed’s balance sheet. This “automatic exit” is an attractive aspect of the approach.

This rate-peg approach to QE would not be designed to inflate asset prices, unlike classic QE which was specifically designed to inflate all asset prices in order to create the “wealth effect.”

Instead, a rate peg of this type is designed to make borrowing cheaper along certain parts of the yield curve, while minimizing the amount of securities the Fed would have to buy to do this. And with the “automatic exit” feature, it would not cause the lingering issues classic QE is now causing. Wall Street hype artists and assorted QE-mongers that have been calling for QE for months would be deeply disappointed with this rate peg approach instead of proper tried-and-true QE.

The Fed shed $46 billion from its balance sheet in April, as total QE Unwind reached $580 billion, and its assets dropped to lowest level since Nov 2013. Read... Fed’s QE Unwind Continues at Full Speed in April