Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, http://www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

“In 30 years, I’ve never seen anything like this”: CEO of warehouse operator Pacific Mountain Logistics.

Sales at merchant wholesalers (except manufacturers’ sales branches and offices) fell 1% in December 2018, compared to November, to $497.2 billion on a seasonally adjusted basis, and inched up only 1% compared to December 2017, according to the Census Bureau estimates this morning.

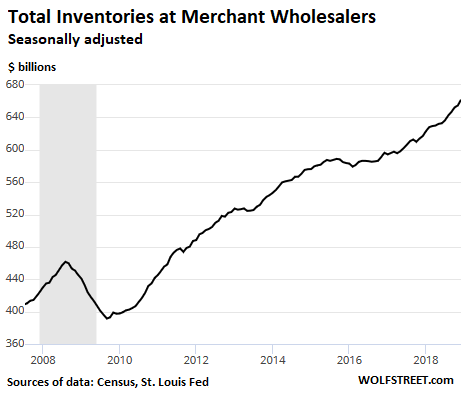

But inventories at these wholesalers rose 1.1% from November and jumped 7.3% from December 2017, to $661.8 billion. Over the two-year period through December, inventories have risen 11%. This includes inventories of durable and non-durable goods (we’ll look at them separately in a moment):

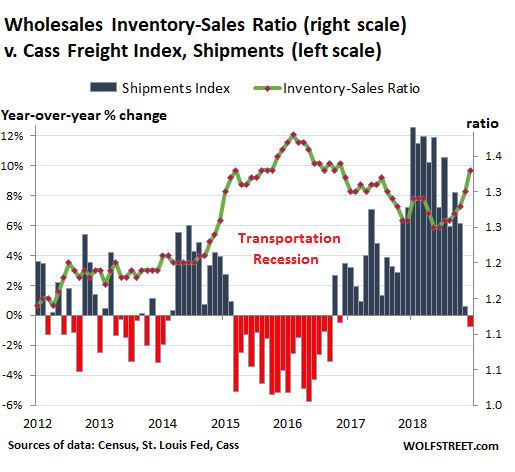

This surge of inventories on soft sales caused the inventory-to-sales ratio so spike to 1.33, up from 1.30 in November and up from 1.25 a year earlier.

This is a familiar pattern. As inventories are piling up, and as inventory carrying-costs rise, companies eventually react: They whittle down their inventories by cutting orders. As we have seen in 2015 and 2016, this hammers the goods-based sectors of the economy. In 2016, it dragged GDP growth down to just 1.6%, the worst growth rate since the Great Recession. The overall economy was barely kept out of a recession by the service sector.

The transportation sector tracked this perfectly as it fell into a steep recession in 2015 and 2016. Now a similar pattern is starting to form: A surging inventory-to-sales ratio as inventories are piling up, while shipment volume of goods, as tracked by the Cass Freight Index, have started to decline on a year-over-year basis.

The Cass Freight Index covers consumer and industrial goods shipped by all modes of transportation — truck, rail, barge, and air — but does not cover commodities such as grains.

I overlaid the two data sets: The Cass Freight Index for Shipments, expressed as percent change from the same month a year earlier (columns, left scale), and the inventory-to-sales ratio (green line, right scale):

Non-durable goods not helpful.

Sales of non-durable goods — food, gasoline, apparel, agricultural products, etc. – at wholesalers fell 1.4% year-over-year in December, even as inventories ticked up 2.2% to $251.2 billion.

The standout here is the category of petroleum and petroleum-products inventories. Inventories and sales are valued in dollars, and the sharp drop in crude oil prices since August caused the dollar amount of petroleum and petroleum-products inventories to drop 12% year-over-year in December. Between September and December, inventories plunged 21% in dollar terms to $20.4 billion.

The problem is in Durable Goods Inventories

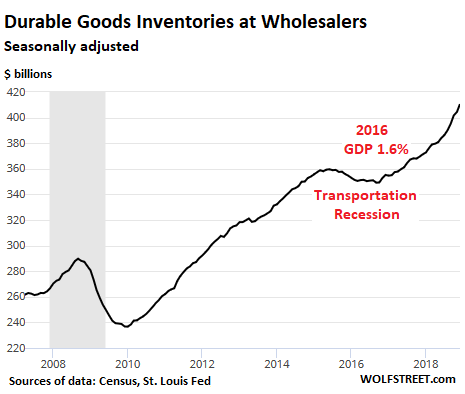

Sales of durable goods by wholesalers ticked up 3.5% year-over-year in December to $245.6 billion. But inventories of durable goods at wholesalers surged 10.6%, to $410 billion – the steepest increase since 2012, the period of inventory restocking coming out of the Great Recession:

Here are some standout categories, in terms of percent change in December 2018, compared to December 2017. Note the three categories with double-digit jumps, two of them relating to the construction sector:

- Furniture & Home Furnishings: +8.9%

- Motor Vehicle & Motor Vehicle Parts & Supplies: 7.3%

- Machinery, Equipment, & Supplies: 12.7%

- Hardware, Plumbing & Heating Equipment & Supplies: 12.1%

- Lumber & Other Construction Materials: 14.9%

- Household Appliances & Electrical and Electronic Goods: 6.5%.

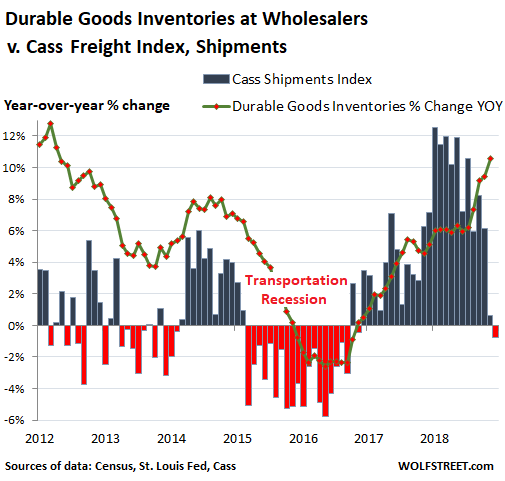

The chart below compares the year-over-year percent change in durable goods inventories at wholesalers to the year-over-year percent change in the Cass Shipments Index. Note the turning point in shipments late last year. Inventories follow with a lag.

This situation of ballooning inventories on soft sales is showing up in the warehousing industry – and it’s getting blamed on companies trying to front-run trade tariffs. The surge of imports ahead of the potential tariffs – coming on top of the usual increase of inventories ahead of the Chinese Lunar New Year – has left warehouses and shipping terminals in Southern California “overstuffed and distribution networks jammed,” the Wall Street Journalreported.

“That stacked-up inventory is straining logistics capacity around the neighboring ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, which together comprise the biggest U.S. trans-Pacific gateway,” the WSJ. It quoted BJ Patterson, CEO of warehouse operator Pacific Mountain Logistics in San Bernardino: “In 30 years, I’ve never seen anything like this,” he said.

Increasing inventories is counted as a business investment and is added to GDP growth; This is what has been happening much of last year. But conversely, the inevitable decline in inventories will be subtracted from GDP growth.

Apocalypse not now

The goods-based sectors comprise the smaller part of the economy. The services sectors dominate. The biggest of them are healthcare, finance, and housing (rents are services). In the US, you cannot get an overall recession with just the goods-based sector slowing down, as we have seen in 2016. It will pull down overall growth in the economy but won’t push the US into a recession. For a recession to happen in the US, the services sectors need to approach the zero-growth line, while the goods sectors are in decline – and that is not yet in sight.

Something has to give. Read… What Trucking & Freight Just Said About the Goods-Based Economy in the US