Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, http://www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

And so far, so good.

The Fed and other central banks have done an endlessly mind-boggling job in killing off any notion of risk – and therefore the pricing of risk – in the bond market, which just veers from curious to curiouser. All kinds of entities, metrics, bond-market watchers, and credit fretters have been warning about the pileup of corporate debt and record corporate leverage.

This is especially the case at the high-yield or “junk” end of the spectrum where cash flows tend to be negative, and where this leverage poses real credit risks. But no problem.

Every time another warning goes out, sure enough the bond gurus at Goldman Sachs and other investment banks that make a killing in fees off underwriting these bonds, and that have to sell these bonds to their clients, come out and soothe our jangled nerves. Don’t worry, be happy, they say; ignore the risks, this is a buying opportunity because this time it’s different.

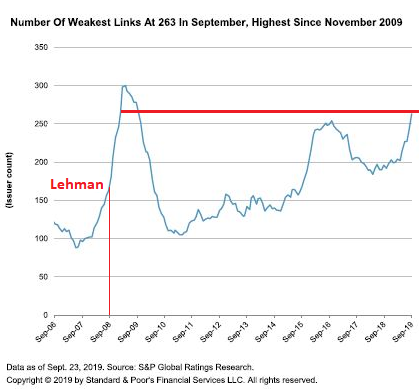

So here we go again. S&P Global Market Intelligence came out with some hair-raising metrics and warnings: “The number of ‘weakest links’ among debt issuers jumped to 263 in September, from 243 in August, marking the highest level since November 2009, when the global speculative-grade default rate was at a record high 10.5% amid the financial crisis.”

The number of “weakest links,” in normal times, would be a key metric. Their default rate is “nearly eight times greater” than that of the broader junk-bond market, S&P says. It defines “weakest links” as companies with a credit rating of “B-” or below, and with negative outlook or whose ratings are on CreditWatch with negative implications, meaning a possible downgrade.

B- is six notches into junk. One step below is “CCC+” which is deep junk, with a substantial risk of default. Two steps further down is CCC-, meaning a default is imminent (here is my plain-English cheat-sheet of corporate credit ratings by S&P, Moody’s, and Fitch).

“The rise in the weakest links tally may signify higher default rates ahead,” Sudeep Kesh, head of S&P Global Credit Markets Research, explained.

The number of weakest links is not at quite the same level as during the peak of the Financial Crisis, but getting nerve-wrackingly close, and is substantially higher than it had been during America’s Lehman Moment in September 2008 (chart via S&P Global Market Intelligence, red marks added):

The hump around 2016 is when credit began to freeze up for the energy sector amid numerous bankruptcies of oil-and-gas companies and coal miners, with fears of contagion spilling over into other sectors.

Five sectors account for 147 weakest links, or 56% of all weakest links (263):

- Consumer products: 52

- Oil and gas: 28

- Media & entertainment: 27

- Retail and restaurants: 22

- Health care: 18

OK, but a couple of days ago, the Wall Street Journal raked the ratings agencies over the coals for being too lenient with companies by not down-grading them when leverage ratios rise beyond a given point. This over-the-coal raking was about the lower end of investment-grade where a one-step or a two-step down grade could reduce those bonds to junk.

“It’s pretty eye-popping if you’ve been doing this for 20-plus years, to see how much more leverage a number of these companies can incur with the same credit rating,” Greg Haendel, a portfolio manager at Tortoise overseeing about $1 billion in corporate bonds, told the WSJ. “There’s definitely some ratings inflation.”

And so the WSJ – falling in line with all the other worry-warts, fretters, and warners about the corporate debt pile-up and record leverage – continued:

Years of rock-bottom interest rates have fueled a boom in borrowing, driving debt owed by U.S. companies excluding banks and other financial institutions to nearly $10 trillion – up about 60% from precrisis levels.

Leverage – how much debt a company owes relative to its earnings – hit a high in the second quarter of this year, according to JPMorgan Chase & Co. data on investment-grade bonds going back to 2004, which also excludes financial companies.

And the “ratings inflation” is likely impacting not only investment-grade bonds, as the WSJ pointed out, but also junk bonds, and the “weakest links.” In other words, reality, which already looks very sobering according to S&P, could look even more sobering. But no problem, not in this bond market where investors are convinced that the Fed has abolished risk and thrown the pricing of risk out the window.

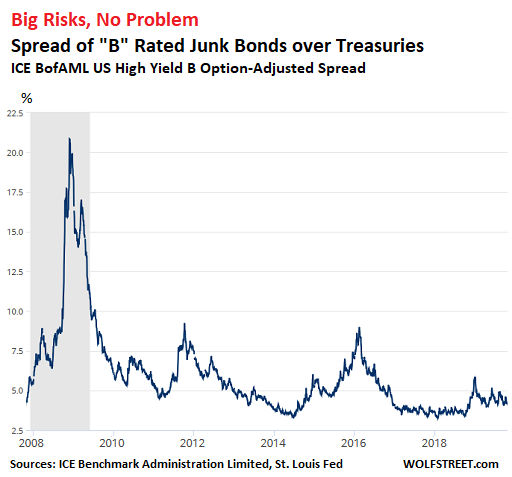

Investors in average B-rated junk bonds currently demand a credit-risk premium of only 4.17 percentage points above the equivalent US Treasury yield, according to the Option-Adjusted Spread of the ICE BofAML US Corporate B Index.

This is less than half the credit-risk premium investors demanded during the 2016 energy-bond credit-freeze (9 percentage points), though there were fewer “weakest links,” and it’s just a fraction of the risk premium investors demanded during the Financial Crisis which exceeded 20 percentage points in November 2008 after the Lehman Moment, and when there were about as many weakest links (chart via St. Louis Fed):

And so now we hear all the reasons why it’s different this time, why the “weakest links” suddenly don’t matter, given the wild yield-chasing these days, why low interest rates have reduced credit risk per-se. We hear that investors don’t have a choice if they want to beat inflation and make a little profit on top of it, and why they have to risk the farm to do so, and why it’s OK that investors are not being compensated for taking these risks.

And so far, so good. If a cashflow-negative company can continue to issue new debt because it has concocted a story that investors want to believe in, engulfed in an environment where central banks have abolished risks, then it can borrow new funds to pay off old investors, no matter what its cashflow is. And as long as the old investors have new yield-chasing investors coming in behind them, there is no problem. The problem arises when new investors wake up and refuse.

How cash-burn machines power the real economy, and what happens to the economy when investors refuse to have more of their cash burned. Read… Here’s What I’m Worried About with the Everything Bubble