It has been living off its real estate portfolio of “owned boxes” for years by selling them.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

Macy’s, the largest surviving department store in the US, and still clinging by its fingernails to the last rung of the top 10 ecommerce retailers in the US, down from 7th place in 2019, may never reopen many of its stores that it hadn’t already decided to shutter before the crisis.

In 2019, 26% of its $24.5 billion in sales were online sales, up from 23% a year earlier, according to its 10-K filing with the SEC. In the second quarter (February through April), as all its stores were closed on March 18, the percentage of digital sales to total sales will surge. But it won’t be enough.

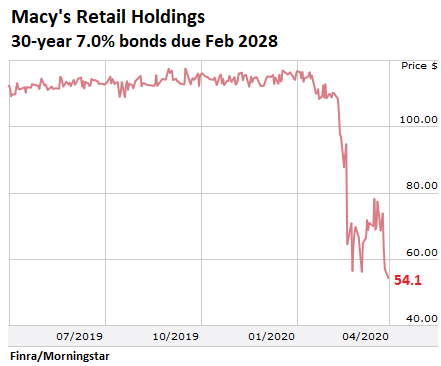

Investors have lost faith, demonstrated amply by the crash of its 7.0% senior unsecured 30-year bond due in February 2028. The bonds have been in deeply distressed territory since mid-March. Since February 14, they have collapsed by 53%, to a new low on Tuesday of 54.1 cents on the dollar, giving them a yield of 18.6% (chart via Finra-Morningstar):

Macy’s is not out of cash. At the end of its fiscal year on February 1, it had $685 million in cash and cash equivalents on hand. On March 20, it said that it drew its entire credit line of $1.5 billion as “proactive measure.” So that would be close to a total of $2.2 billion in cash. But part of the cash has already been burned.

The bond market believes that there is a decent chance these $2.2 billion and whatever else Macy’s may be able to pull out of its hat – more on that in a moment – will get it through the first part of 2021 without filing for bankruptcy. This is shown by its $500 million in senior unsecured 3.45% notes that are due on January 15, 2021. These notes traded at 92.5 cents on the dollar today. This indicates that the market still sees a decent chance of getting paid face value in January, 2021.

It’s never comforting for bondholders when the Chief Financial Officer of a company in distress suddenly departs. But that’s what happened on April 7, when Macy’s announced that CFO Paula Price would “voluntarily depart,” effective May 31. Macy’s is now scrambling to find a successor. After her departure, she will stay on as an advisor for six months to smoothen out the transition, for $510,000 in advisory fees and other benefits worked out in the agreement.

Ms. Price was likely instrumental in Macy’s decision to lay off “the majority” of its 123,000 employees after it had closed all its Macy’s, Bloomingdale’s and Bluemercury stores on March 18.

Macy’s vendors, if they’re worried about getting paid for their merchandise and want to obtain credit insurance, face a new challenge: Two of the largest credit insurance providers, Coface SA and Euler Hermes Group SAS, have stopped writing policies to cover Macy’s, said people with knowledge of the matter, according to Bloomberg today. This is a sign that insurers have lost faith in Macy’s ability to pay its vendors.

This whole thing is going to be a mess. If Macy’s stores reopen in the summer, the merchandise – the part it couldn’t sell online – will have been there for months. With some things, that’s OK. With other things, it’s not. But vendors might be getting skittish, now that credit insurance is harder to come by, or more expensive.

Vendors may begin to protect themselves, limiting their exposure and demanding shorter payment terms – the opposite of what Macy’s had announced in March, that it would be “extending payment terms” to stretch out its cash. This will make it even harder for Macy’s to restock its stores with appropriate fresh merchandise before they reopen.

To stay out of bankruptcy court, Macy’s is now trying to pull a big rabbit out of the hat: borrow up to $5 billion, secured by stores it owns and by merchandise, sources told CNBC and Bloomberg last week.

The sources said that $3 billion of the debt could be backed by inventories as collateral. And that $1 billion to $2 billion could be backed by real estate.

Macy’s owns 342 of 775 stores it still operated as of February 1. None of these “owned boxes,” as it calls them, were encumbered by a mortgage, it said in its 10-K. It also owns some other properties. For years already, Macy’s has been “monetizing,” as it calls it, this real estate portfolio through the sale of properties.

In one of the most expensive property markets in the US, San Francisco, Macy’s already sold three of its four stores:

- 2016: its 263,000 sq. ft. Men’s Store on Stockton St. (now being redeveloped into offices and mixed use) a couple of blocks from Union Square, for $275 million.

- 2017: its 280,000 sq. ft. store at the Stonestown Galleria (an aging mall with plans to redevelop it, including possibly into housing) for $41 million.

- 2019: its historic 250,000-square-foot I. Magnin building at Union Square for $250 million.

By now, the proceeds from those sales have been used up. Macy’s still owns its last remaining store in San Francisco, its flagship 700,000 square-foot store facing Union Square, the largest department store in the Bay Area.

Its other crown-jewel “owned box” is its Herald Square location in Manhattan. But the source that disclosed the efforts to raise up to $5 billion said that it would not be used as collateral. The remaining “owned boxes” are much less valuable, and some of them may have little value.

Macy’s has been living off its real-estate sales for years. But it still has significant resources in its property portfolio that it could leverage, including, if push comes to shove, its San Francisco Union Square store and its Manhattan Harold Square store.

This comes in an era when, according to Green Street Advisors, mall properties across the US have lost about 30% of their value since 2016, and 20% year-over-year in March. With the total brick-and-mortar meltdown now under way, and with the new uncertainties of the health crisis going forward, and with the current issues in the commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) market, selling retail properties is going to be tough; using them as collateral for new debt might be easier.

Macy’s might burn through $2 billion in cash this year. It has to refinance the $500 million bond in January 2021. It also has to refinance a $450 bond in January 2022. And it will continue to burn cash in 2021. So the cash proceeds from the $4 billion or $5 billion in new debt, if Macy’s succeeds in selling it, may get it through 2021. But then what?

It will be getting close to the end of its rope. For a while longer, it can continue to burn its furniture to stay warm, so to speak, and like Sears Holdings, ruin its brand and collapse into worthless debris.

If Macy’s can use a bankruptcy filing sooner rather than later to shed most of its stores, keep a few flagship stores, lighten its debt load, and concentrate its remaining resources on building its online brand and fulfillment infrastructure, it might have a better chance of staying relevant as an internet brand — and forget the department store.