Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, http://www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

Despite repeated speeches to the contrary.

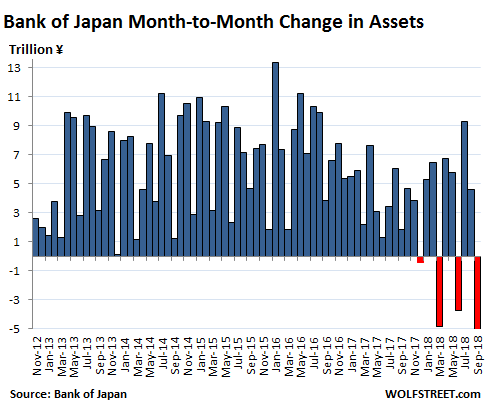

As of September 30, total assets on the Bank of Japan’s elephantine balance sheet dropped by ¥5.4 trillion ($33 billion) from a month earlier, to ¥537 trillion ($4.87 trillion). It was the fourth month-over-month decline in a series that started in December. This chart shows the month-to-month changes of the balance sheet. Despite all the volatility, the trend since mid-2016 is becoming clear:

Abenomics became the economic religion of Japan in later 2012, and “QQE” (Qualitative and Quantitative Easing) was an integral part of it. So has the “QQE Unwind” commenced? Are central bankers, even at the Bank of Japan, getting cold feet about the consequences?

At BOJ policy meetings, concerns have been voiced over the “sustainability” of the stimulus program, according to the minutes of the July meeting, released on September 25. So the BOJ staff “proposed measures to enhance the sustainability of the current monetary easing while taking into consideration, for example, their effects on financial markets.”

And “flexibility” has been proposed as solution to those concerns.

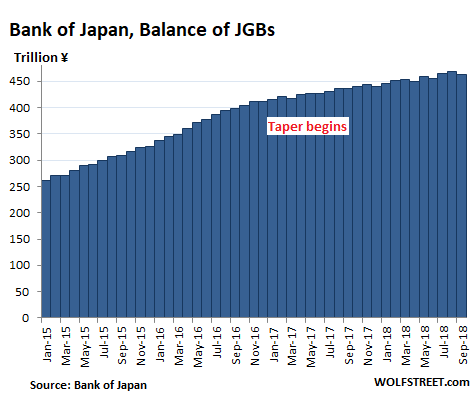

The minutes reiterated that the BOJ would continue to buy Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) in “a flexible manner” so that its holdings would increase by about ¥80 trillion a year.

But this is precisely what has not been happening, in line with this “flexibility.” Over the past 12 months, the BOJ’s holdings of JGBs rose by “only” ¥26.2 trillion – not ¥80 trillion. And they declined in September from the prior month (more in a moment).

Shortly after the minutes had been released, BOJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda, once the most reckless among the money printers, changed his tune and said in a speech that, “in continuing with powerful monetary easing, we now need to consider both its positive effects and side-effects in a balanced manner.”

The Fed has already whittled down its balance sheet by $285 billion since it started its QE unwind last October.

The ECB has tapered its QE from a peak of buying €85 billion a month to buying €15 billion currently and will end it altogether in December. The discussion has switched to raising rates and unwinding QE.

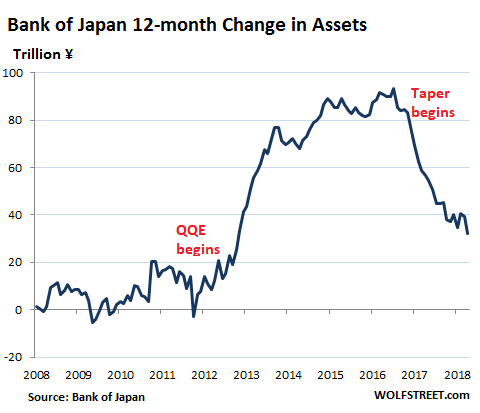

At the BOJ, during peak QQE, assets ballooned by ¥93.4 trillion in the 12-month period ended December 31, 2016. The recent ups and downs of its balance sheet had the effect that over the 12 months ended September 30, it added only ¥32.1 trillion to its balance sheet:

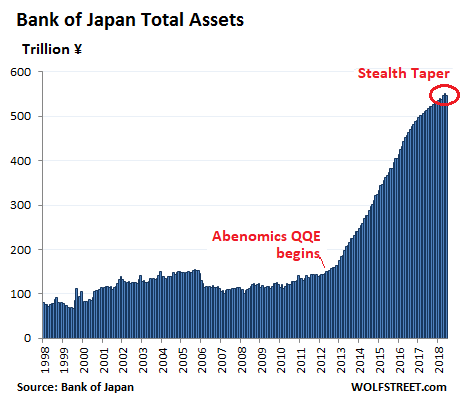

Total assets on the BOJ’s balance sheet have reached about 100% of Japan’s GDP (¥540 trillion), compared to the Fed’s balance sheet which at its peak in Q1 2015 amounted to about 25% of US GDP and has now dropped to 20.5%. Given the unimaginable magnitude of the pile, the BOJ’s tapering is barely noticeable:

The BOJ has been buying mostly Japanese government securities (JGBs and short-term bills), but also equity ETFs, Japanese REITs, and corporate bonds. Japanese government securities are the largest asset class on the balance sheet. By now, the BOJ has acquired about 50% of all outstanding Japanese government debt — up from about 14% in late 2012.

But the amount of these government securities on the BOJ’s balance sheet fell in September from the prior month, to ¥462.1 trillion.

For the 12-month period ended September 30, the BOJ added “only” ¥26.2 trillion of these securities, down from around ¥85 trillion during the QQE peak years, and a far cry from its assertions, most recently made in the meeting minutes released in September, that it would add ¥80 trillion a year. In fact, it has not added ¥80 trillion in a 12-month period since the 12-month period ended April 2017. So whatever the BOJ may proclaim, it has been tapering its asset purchases, but not in any consistent manner, to keep everyone guessing.

Japan, by far the most over-indebted country in the world in relationship to its economy, has decided that there will be no debt crisis. A debt crisis would force Japan to brutally cut its budget for social services and raise taxes by large amounts to make ends meet. Japan has decided that it would never come to that. Instead, there may be a currency crisis or an inflation crisis, or both, which would spread the pain more evenly.

Japan can weather this type of crisis better than other countries because it has a large trade surplus and a large pile of foreign exchange reserves, though it would whittle down the wealth and purchasing power of the people. So this type of crisis will be kicked down the road for as long as possible. And that could be quite a while.

What Japan will never have is a debt crisis since the government bond market is in total control of the BOJ. Given the extent of its control over the market, the BOJ can now ease up on buying these JGBs. But market forces will never be allowed mess with that market.