Here’s the story of two student housing REITs in the UK that crashed.

Wolf here: In recent years, student housing, a subcategory of Commercial Real Estate, became one of the hottest asset classes in the US, in the UK, and elsewhere. Big money piled in. Wall Street raked in the fees by securitizing the mortgages into commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS). Large firms spun off their portfolios of student housing buildings into publicly traded REITs. The article below is about two of those REITs in the UK, but the issues are the same in the US. This asset class is risky even in good times because students are not stable renters. Last fall, long before Covid-19 showed up, delinquencies and special servicing rates on US student housing CMBS already spiked. The pandemic has now been heaped on top of it.

By Nick Corbishley, for WOLF STREET:

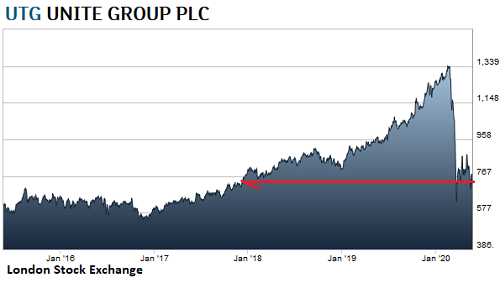

When it comes to over-priced acquisitions at peak hype, there is no worse time than just before a financial crisis. The UK’s largest student housing real estate investment trust (REIT) Unite Group fell into that trap. In November 2019, it spent £1.4 billion to buy up privately-owned student housing provider Liberty Living Group plc, from the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board. In the process, it more than doubled its net debt, from £856 million to £1.88 billion. The day after the deal was sealed, Unite’s CEO said the enlarged group would “be well positioned to meet the growing need for affordable, high quality student accommodation in university towns and cities where demand is strong.”

That need, instead of growing, has all but vanished. Since March 11, all UK university campuses have been closed due to the virus outbreak. Most students have gone back home.

In late April, Unite Group informed investors that it had been inundated with cancellation requests since offering to waive rents for students who did not plan to occupy their rooms in the final term. Based on requests received up to that point, between 43,000 and 46,000 students would not pay rent this semester, the company said. The total number of vacated beds is the equivalent of 65% of Unite’s portfolio.

As a result, the company said it expected a fall in income from the 2019/20 academic year of 16-20% on a Group share basis, or £125 million, which it said was an improvement on its previous forecasts. But that was before Cambridge University’s bombshell announcement last Thursday that it was cancelling all face-to-face lectures for the entire 2020-2021 academic year, fueling speculation that many students will stay away next year too.

“Given that it is likely that social distancing will continue to be required, the university has decided there will be no face-to-face lectures during the next academic year,” the university said in a statement. “Lectures will continue to be made available online and it may be possible to host smaller teaching groups in person, as long as this conforms to social distancing requirements.”

Given Cambridge University’s import and influence, the move is likely to trigger a cascade of similar announcements from other higher education institutions. If that happens, student life in the UK is set to be a more insular experience for the foreseeable future, dealing a massive blow not only to students, professors, lecturers and other university staff but also to the businesses and communities that have come to depend on the income they generate.

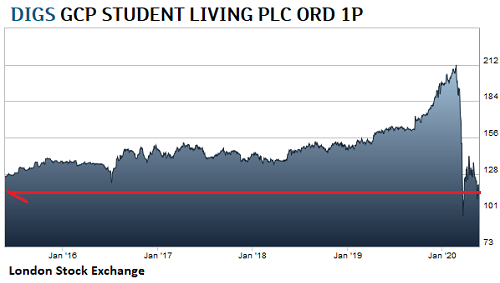

Those businesses include big corporate providers of student accommodation and private landlords, some of whom have continued to charge students for digs they no longer occupy. Many of these companies have enjoyed years of surging profits on the back of years of soaring student rents. One of the largest REITs, GCP Student Living, reported a 51% rise in profits in its last financial year alone. GCP was the first REIT invested exclusively in student housing when it came to the market in 2013, and since then has given its investors a return of 12.9% a year.

But that was before the arrival of Covid-19 and the UK government’s subsequent imposition of lockdown and social distancing measures put its entire business model on hold. The shares of both GCP and Unite Group have slumped by 47% in the past three months. GCP’s stock is now trading at the same price it was trading at in October 2014. In the case of Unite Group, some £2.5 billion has been wiped off its market cap since the coronavirus crisis began.

Unite has already had to come to terms with the likelihood that many foreign students — a key customer segment — will be staying away from the UK, at least for the next year, and is now focusing most of its marketing activities on UK-domiciled students. For British universities and the businesses that have sprouted up around them, overseas students have become a vital source of income. For a start, they pay twice as much or more in fees than UK students, who pay £9,250 a year.

China is the largest source of international students in the UK, with 115,014 study visas issued to Chinese students in 2019 – 45% of all such international visas. But according to a British Council survey of 11,000 Chinese students considering studying in the UK next year, 22% say they are likely or very likely to cancel their study plans. Another 39% say they are still undecided about whether to cancel.

It’s not just foreign students who are having second thoughts. A recent survey of UK-domiciled undergraduate applicants found that more than one in four students are willing to delay starting their courses if universities are not operating as normal due to the coronavirus pandemic. As such, if many universities follow Cambridge’s lead and cancel face-to-face classes and enforce strict social distancing, there would be 120,000 fewer students when the academic year begins in autumn.

That, coupled with the diminished numbers of overseas students, means British universities are now staring at a gaping hole in future revenues. To plug that hole, they’re already asking the UK government for a £2.2 billion rescue package, which the government has so far turned down. By Nick Corbishley, for WOLF STREET.