Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, http://www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

It’s a tough job, but someone’s doing it.

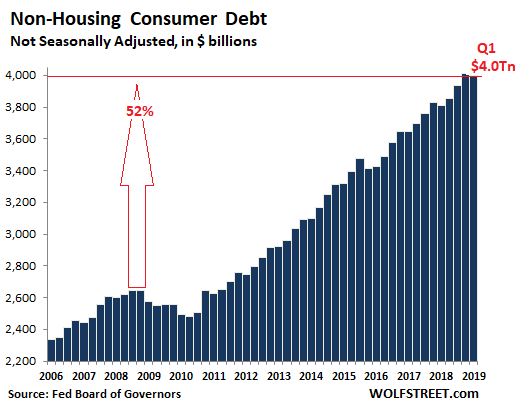

Consumer debt – or consumer “credit” more euphemistically – includes auto loans, student loans, credit-card debt, and personal loans, but it excludes housing related debt, such as mortgages and HELOCs. Growing consumer debt helps prop up the US economy because it means that consumers – they’re called “consumers” not “people” for a reason – spend money they don’t have. There is always a reckoning in the future, but to heck with the future, and so here we go.

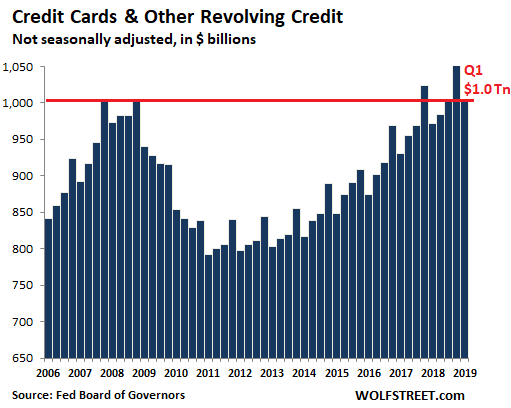

Revolving credit

Credit card debt and other revolving credit, such as personal lines of credit, in Q1 rose 3.4% compared to Q1 last year, to $1.0 trillion (not seasonally adjusted), according to the Federal Reserve Tuesday afternoon. This was a record for a first quarter, when consumers cut back while they try to dig themselves out from under their shopping season debts. But it wasn’t good enough. Credit card balances in Q1 were flat with Q4 2008, despite a decade of inflation, population growth, and economic growth. Our debt slaves are lackadaisical:

The thing is, over the same period, nominal GDP rose 5.1%. And in terms of GDP, credit card debts actually fell, which explains the soft-ish retail data in the first quarter. In a very un-American way, consumers were again lackadaisical in charging up their credit cards to the max.

Credit cards are a key element in the banking industry’s profits. At commercial banks, the average interest rate on credit-card plans is 15.1% and the average assessed interest rate is 16.9%, on $1 trillion in outstanding credit balances. This amounts to around $150 billion to $169 billion a year in interest income! These banks rely on consumers to spend money they don’t have. So why don’t they consume with sufficient energy? That’s a baffling question for economists.

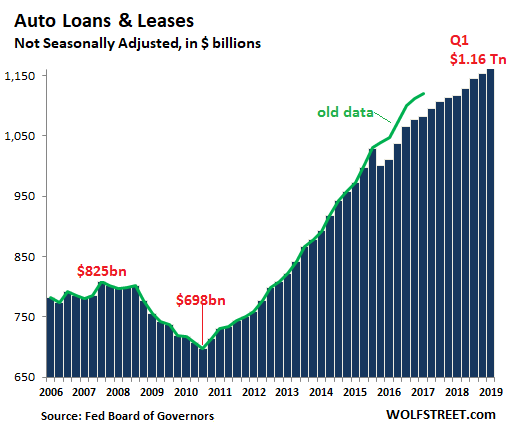

Auto loans and leases

Total auto loans and leases outstanding for new and used vehicles in Q1 rose by $44.5 billion from a year ago, or by 4.0%, to a record of $1.16 trillion, despite new-vehicle sales that declined in Q1 by 3.2%, though there was some strength in used vehicles sales. The increase in borrowing was due to higher transaction prices of new and used vehicles, the rising average loan-to-value ratio, and the lengthening average duration of loans:

The green line in the chart above is a reminder that this type of data gets revised as new data becomes available. In September 2017, the Federal Reserve adjusted its data of consumer credit back to Q3 2015, based on the new five-year Census survey, and auto loans got the bulk of the revisions. The green line shows that the car business didn’t collapse in Q3 2015 but that the drop in outstanding auto loans was due to a revision.

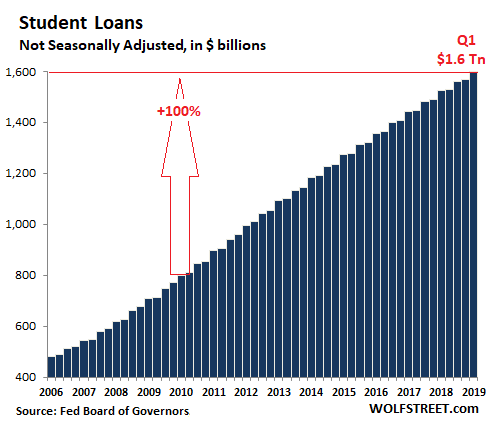

The student-loan economy

Student loans rose by 4.9% year-over-year in Q1, or by $74 billion, to a new record of $1.6 trillion (not seasonally adjusted). It has doubled since the beginning of 2010. Confusingly, enrollment in higher-education, based on the latest data available from the National Center for Education Statistics fell by 7% between 2010 and 2016.

In other words, fewer students are enrolled, but all combined they borrow more as tuition continues to rise, and as the entire industry feeds on those government-guaranteed student loans. This ranges from device makers, such as Apple, text-book publishers, concert-ticket sellers, and commercial real estate investors specializing in student housing. Every dime a student borrows is spent, and it props up Corporate America, the university financial complex (UFI, my term), and the US economy overall – with heck to pay later:

All three forms of non-housing consumer debt combined – revolving credit, auto loans, and student loans — rose by a respectable $191 billion in Q1 from a year ago to $4.0 trillion, carried by surging student loans and auto loans:

Every dime of this $191 billion in new debt was plowed into consumption, and therefore into GDP. This increase in consumer debt over the 12 months added nearly 1% to GDP, and that’s why consumers have to spend money they don’t have. It’s their job. Everyone depends on them. The other side of the coin is that these debt slaves now owe $4 trillion that they must pay interest and principal on for all times to come. And inflation won’t help them because rising inflation will cause these rates to rise, and our debt slaves will just have to work that much harder to deal with their debts.