Just how much lower can they go? To Zero. And the ECB’s negative interest rates are driving them closer to it.

By Nick Corbishley, for WOLF STREET:

Over the past three weeks, stocks in Europe have plunged by 22.5%, their worst decline since the collapse of Lehman Brothers. The sell-off has been across the board but the worst of it has been reserved for the banking sector, whose shares have been relentlessly crushed and re-crushed for 13 years.

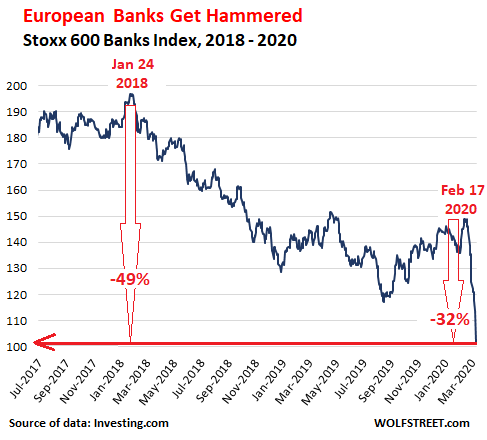

On Monday, the Stoxx 600 Banks index, which covers major European banks, plunged 13%. Today, after a knee-jerk bounce-back that then fizzled, the index closed essentially flat, back where it had been in March 2009. It has collapsed in a nearly straight line by 32% since February 17, when this latest Coronavirus-triggered sell-off began, and by 49% since January 24, 2018:

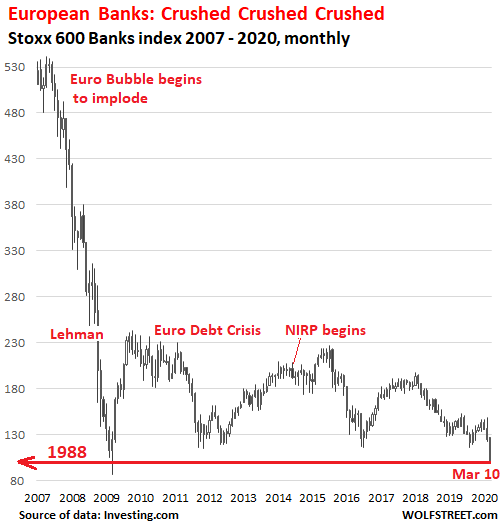

But it’s even worse: The Stoxx 600 bank index has collapsed by 82% since its peak in May 2007, after having quadrupled over the preceding 12 years. It was the frenzied height of the euro bubble and the sky was supposedly the limit for Europe’s biggest banks. Things got so crazy that for a brief moment in 2008, before it all come tumbling down, the Royal Bank of Scotland, now bailed-out and majority state-owned, was the world’s biggest bank by assets.

Here’s how far the shares of Europe’s largest publicly traded banks by assets fell on Monday (and in parentheses: at today’s close, since February 17):

- HSBC (UK): -4.82% (-17%)

- BNP Paribas (France): -12% (-33%)

- Credit Agricole (France): -16.9% (-42%)

- Deutsche Bank (Germany): -13.6% (-38%)

- Banco Santander (Spain): -12% (-30%)

- Barclays (UK): -9.81% (-32%)

- Société Générale (France): -17.65% (-41%)

- Lloyds Bank (UK): -8% (-24%)

- ING (Netherlands): -14% (-37%)

Today, banks in Northern Europe rebounded a tad from yesterday’s lows. But banks in Italy and Spain, having started the day in the green, closed with some big drops:

- Unicredit (Italy): -3.6% (down 10% from intraday high)

- Intesa (Italy): -2.5%

- Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena (Italy): -6.3%

- Banco Sabadell (Spain): -7.1%

- Santander (Spain): -1%

Three of the biggest sell-offs over the past three weeks were endured by France’s three largest lenders: BNP Paribas (-33%), Credit Agricole (-42%), and Société Générale (-41%).

These declines in share prices, while impressive for both their speed and size, represent just one more leg down in the relentless sell-off that began in May 2007 and has dragged the Stoxx 600 82% lower, to just below where it was in January 1988.

The ECB is primarily concerned with keeping the Eurozone glued together. Unlike the Fed, whose 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks are owned by the banks and bank stocks are hugely important to the Fed, the ECB couldn’t care less about bank stocks, as long as banks themselves don’t collapse. So it has thrown just about everything it has at the problem of keeping the Eurozone glue together, including €4.7 trillion ($5.2 trillion) of newly conjured money, but with largely undesirable consequences for banks and their shares:

Here’s the handy and continuously expanding WOLF STREET timeline of some of the events that helped annihilate European bank stocks:

- In mid-2007, the euro bank bubble begins to implode.

- In 2008, the Financial Crisis hits, lighting the spark to housing market collapses in Spain, Ireland, Portugal, Greece, et al.

- In 2009, the euro sovereign debt crisis along with the Southern European banking crisis starts.

- In June 2014, the ECB’s Negative Interest Policy (NIRP), designed to solve these problems, begins decimating banks’ interest margins while also wiping out savers.

- In 2015, the Italian banking crisis resurfaces with the slow-motion collapse of Monte dei Paschi, Veneto Banca and Banca Popolare di Vicenza, and their subsequent bailout/takeover over a year later.

- In June 2016, a majority of British voters check the Brexit box, which causes the Stoxx 600 Bank index to plunge 21% in two days, the worst two-day plunge ever.

- In mid-2017, mid-sized Spanish lender Banco Popular collapses under the weight of its huge bad loan-infested balance sheet, and is taken over by Banco Santander.

- In early 2018, Deutsche Bank and other banks recommence their downward spiral.

- By late 2018, even the ECB begins to acknowledge the harm that negative interest rates does to banks’ ability to turn a profit and the risks it poses to financial stability, by encouraging banks to engage in greater risk taking and less productive lending.

- In late February 2020, COVID-19 upends the global economy, and the risks are piling up in one of the euro area’s weakest links, the banks, and particularly Italy’s banking system.

Already home to one of the highest concentrations of bad bank debt in Europe, Italy can ill afford the current shutdown of its economy that could lead to a fresh surge in nonperforming loans. The country is already either on the verge of recession, or in the very midst of one. Italy’s banking lobby, ABI, has called for a state guarantee and a 6-12 month moratorium on new, stricter EU regulations on problem loans. This would offer small firms affected by the virus-crisis the opportunity to freeze repayments or lengthen the maturity of loans.

The government has also proposed passing an emergency law that would suspend mortgage repayments for bank customers for the duration of the shutdown. Another possibility is that the government, if given the green light from the EU, pays the interest costs on behalf of its citizens.

Such measures could prove to be a life-line for struggling businesses and households. But they will also cost a lot of money, and that is one thing in short supply for Italy’s government, whose total public debt load is now equivalent to almost 140% of GDP. Just two weeks ago, as COVID-19 was gaining a foothold in the country, the European Commission warned of the “high” risks Italy faces in trying to refinance its mountain of debt. “The need to roll over sizable amounts of debt, at around 20% of GDP per year, still exposes Italy’s public finances to sudden rises in financial markets’ risk aversion,” the commission said.

Italian bond yields are already beginning to rise, albeit from an absurdly low level. The spread between the country’s ten-year bond and that of Germany’s blew out to more than 200 basis points for the first time since August. That is bad news not only for Italy’s government but also for the shaky banks in Italy and beyond that have bought huge chunks of its ostensibly risk-free debt. If the yields on that debt suddenly begin to spike as bond prices drop, it could significantly erode lenders’ capital buffers. And that is when investors begin to worry, prompting them to intensify their sell-off of bank shares.

To try to stop that from happening, the ECB may be tempted to take deposit rates, already at -0.5%, even lower. But while that may provide fiscally challenged governments with a little extra breathing space to support their stalling economies, it will also heap further pressure on banks, effectively destroying their basic business model, as bank CEOs have been loudly bemoaning. To mitigate this problem, the ECB may come up with some other magic solution, such as buying the banks’ bonds, but as with NIRP and QE-forever, the remedy will probably be worse than the disease. By Nick Corbishley, for WOLF STREET.