The ECB promised “to monitor markets closely.” Then it came out with a new bond buying binge.

By Nick Corbishley, for WOLF STREET:

Bank stocks in Europe plumbed fresh mutli-decade lows despite the release of a hurriedly improvised one-paragraph announcement by the ECB pledging to do just about whatever it could take to keep the banking system in tact. The ECB will continue “to monitor markets closely”, the message read, and is “ready to adjust all of its measures, as appropriate, should this be needed to safeguard liquidity conditions in the banking system.” In other words, the ECB is willing to throw what remains of the kitchen sink at the problem.

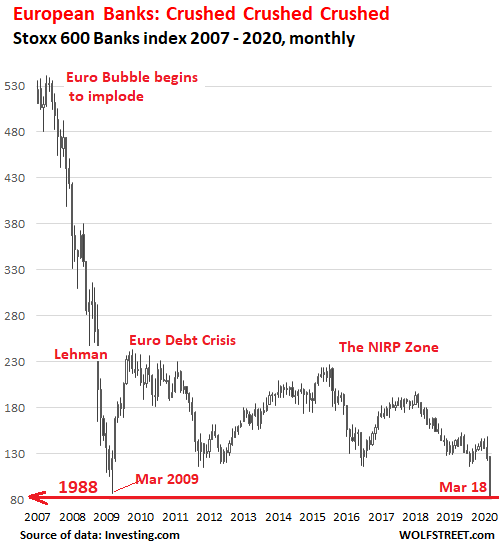

The message may have been intended to reassure investors, calm market jitters, and stop the sell-off of sovereign bonds and bank shares but if anything, it had the opposite effect. The Stoxx 600 Banks index, which covers major European banks, fell 3.7% to close at 83, below even the multi-decade low of 87 in March 2009, at the bottom of the first Financial Crisis this century. Today’s close was the lowest since February 1988, during the sell-off that followed Black Monday in October 1987. The index has collapsed by 85% since its peak in May 2007, after having quadrupled over the preceding 12 years:

The almost vertical collapse of those shares over the past four weeks is but the latest episode in a 13-year story of decline. The Stoxx 600 bank index has slumped by 85% since its peak in May 2007,

But what is the ECB going to do to rescue bank shareholders? Not much. The ECB is primarily concerned with keeping the Eurozone duct-taped together. Unlike the Fed, whose 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks are owned by the banks in their districts, and to whom bank stocks are therefore hugely important, the ECB couldn’t care less about bank stocks, as long as the banks themselves don’t collapse. So it has thrown just about everything it has at the problem of keeping the Eurozone in tact, including conjuring up €4.7 trillion ($5.2 trillion) of fresh money, and pushing its policy rates and many bond yields into the negative, but with largely undesirable consequences for banks and their shares.

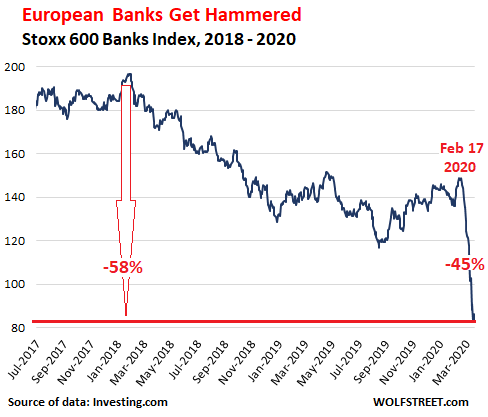

On top of it comes the impact of the coronavirus. The Stoxx 600 Banks Index has plunged 45% since February 17, going to heck in a (nearly) straight line, and is down by 58% since January 2018:

By all appearances, we are headed into yet another full-blown financial crisis, triggered not by the banks this time but by the response to the coronavirus, which is now reverberating throughout the system and hitting the already weak banks. So far, neither the Fed nor the ECB have managed to get a grip on this new crisis, which is moving far faster than the last one.

Bank bonds are selling off, particularly the “senior non-preferred bonds,” a new creature road-tested three years ago by France’s biggest bank. These bonds lured many investors with the promise of a slightly positive yield. It’s “bail-in-able” debt. In return for the tiniest of returns (say, a yield of 2%), you basically get to hold debt that can be turned into worthless equity or be cancelled the moment a bank begins to wobble. Not surprisingly, investors are trying to offload them as quickly as they can, reports the FT.

Today, the ECB, in a bid to reassure investors, said that it is directly intervening in sovereign debt markets with a €750 billion bond-buying binge for the rest of 2020, including Greek bonds for the first time, and Italian bonds, whose yields have spiked sharply in recent days. Italian bonds are held in huge numbers by banks all over the continent, particularly Italian and French ones. The more they fall, the weaker the banks’ capital buffers get. Despite the ECB’s intervention, the yield on the ten-year bond still rose by over 5% today to 2.43%, its highest level since last last June.

The ECB also walked back prior remarks by Austrian central-bank governor Robert Holzmann that suggested that the ECB would take little further action beyond cutting interest rates even further into negative territory, which has been decimating banks’ interest margins for years, and providing emergency liquidity lines for the same banks that are being slowly killed by the negative interest rates.

No publicly listed lender, big or small, has been spared by the latest rout. Below, in descending order, is a list of the worst-hit large publicly traded banks in Europe. The first percentage is the amount by which the bank’s shares have fallen since February 17, when the Coronavirus began spreading like wildfire through northern Italy, causing everything to go to heck. In parentheses is the amount by which they have fallen since Jan 1, 2018. We’ll leave it up to your imagination what the percent-drop from the peak in May 2007 would look like:

- Société Générale (France): -56% (-67%)

- ING (Netherlands): -54% (-73%)

- Credit Agricole (France): -53% (-57%)

- Santander (Spain): -52% (-64%)

- Barclays (UK): -53% (59%)

- BNP Paribas (France): -52% (-58%)

- Unicredit (Italy): -51% (-57%)

- Deutsche Bank (Germany) -50% (-68%)

- Credit Suisse (Switzerland): -49% (-62%)

- RBS (UK, majority state-owned): -39% (-54%)

These ten banks are Europe’s financial flag carriers. Though some of them have been shrinking in size, complexity, and risk, including Deutsche Bank. Nonetheless, they are still recognized as global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) due to the size, scope and inter-connectedness of their assets. If any one of them collapses it will set off a shock wave throughout the global financial system.

Many of Europe’s second-tier banks, whose collapse would have significant repercussions at the regional level, at the very least, have also seen their shares plunge in the past four weeks. Spain’s BBVA is down 52% (and 64% since Jan 2018), Germany’s Commerzbank, in which the state still holds are big share from the last bailout, is down 54% (and -75%). Italy’s Intesa Sanpaolo is down 44% (and 50%).

While the recent share collapse of seventh and eighth-placed Unicredit and Deutsche Bank has been slightly less pronounced than many of the region’s other large banks, their overall decline since the global financial crisis has been far greater than any of their other peers. Deutsche Bank has lost more than 95% of its market value since 2007 and Unicredit more than 98%. By Nick Corbishley, for WOLF STREET.