Fed shed MBS. Loans to “SPVs” flat for fifth week. Repos in disuse. Fed still hasn’t bought junk bonds, stocks, or ETFs. But it sure sent Wall Street dreaming.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

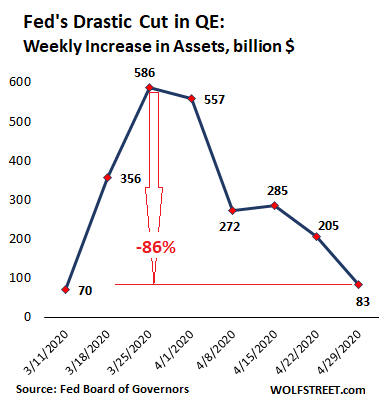

Total assets on the Fed’s balance sheet rose by only $83 billion during the week ending April 29, to $6.656 trillion. That $83 billion was the smallest weekly increase since this show started on March 15, and down by 86% from peak-bailout in the week ended March 25. This chart shows the weekly increases of total assets on Fed’s balance sheet:

The Fed is thereby following its playbook laid out over the past two years in various Fed-head talks that it would front-load the bailout-QE during the next crisis, and that, after the initial blast, it would then cut back these asset purchases when no longer needed, rather than let them drag out for years.

On January 1, the balance sheet stopped expanding as the Fed’s repo market bailout had ended. However, in late February, all heck was breaking loose, and the Fed first increased its repo offerings and then on March 15, started massively throwing freshly created money at the markets, peaking with $586 billion in the single week ended March 25.

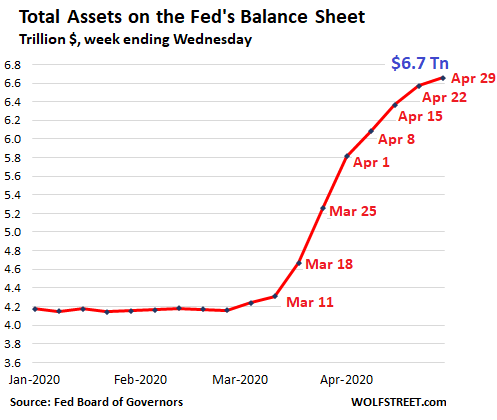

But since then, the Fed has slashed its weekly increases in assets, which shows up in the flattening curve of the Fed’s total assets in 2020:

The Fed cut its purchases of Treasury securities. The balance of its mortgage-backed securities (MBS) actually fell. Repurchase agreements (repos) have fallen into disuse. Lending to Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) has not gone anywhere in five weeks. And foreign central bank liquidity swaps, after spiking in the first two weeks, only rose modestly, with most of the increase coming from the Bank of Japan, which is by far the largest user of those swaps.

Purchases of Treasury securities get slashed.

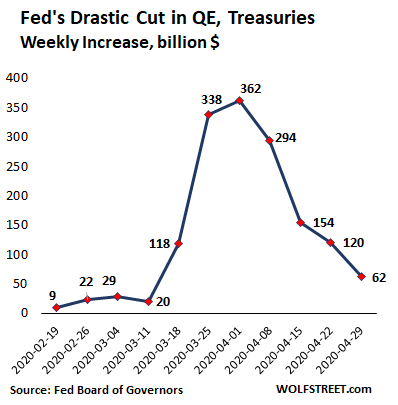

The Fed added only $62 billion of Treasury securities to its balance sheet during the week, the smallest amount since this show began, down 83% from the $362 billion during peak-Wall-Street-helicopter-money. This chart shows the weekly increases of Treasury securities on the Fed’s balance sheet:

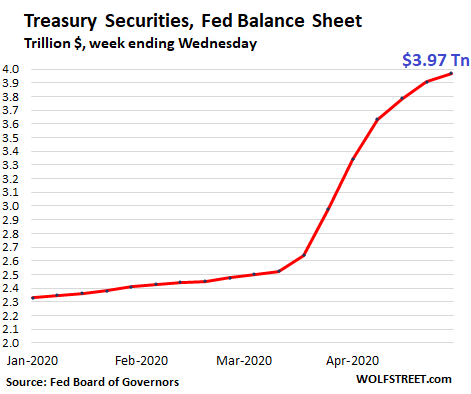

The chart below shows this effect: The curve of Treasury securities has been flattening over the past few weeks, after the massive frontloading of purchases in March. The total is now $3.97 trillion:

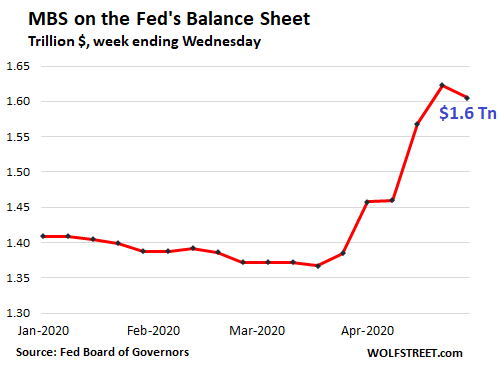

MBS purchases and balances fell.

The Fed has drastically cut its purchases of mortgage-backed securities over the past five weeks, as reported by the New York Fed transaction summary (net purchases, for the weeks ended):

- $157 billion (Mar 25)

- $145 billion (Apr 1)

- $109 billion (Apr 8)

- $58 billion (Apr 15)

- $56 billion (Apr 22)

- $38.5 billion (Apr 29)

MBS trades take weeks to settle. All of the $38.5 billion in MBS the Fed bought this week will settle in May. Since the Fed books the MBS trades only after they settle, the balance sheet lags by some time the actual trades.

In addition, if the Fed buys no MBS at all, the MBS on its balance sheet will decline due to the pass-through principal payments that all holders of MBS receive as the underlying mortgages are paid down or are paid off. There is currently a boom in mortgage refinancing underway, which creates a torrent of these pass-through principal payments. Just to keep its MBS at a steady level, the Fed would need to buy a significant amount of MBS.

This combination of drastically lower purchases, the erratic settlement dates, and the torrent of pass-through principal payments caused the balance of MBS on the Fed’s balance sheet to fall by $18 billion, to $1.6 trillion:

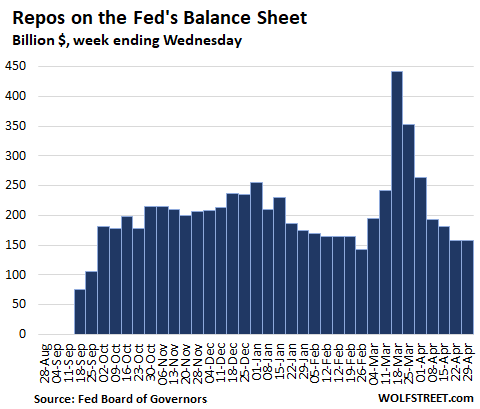

Repos fall into disuse.

In recent weeks, there has been no demand for the repurchase agreements the Fed offers in the repo market. The repo market itself is running as it normally does, a multi-trillion-dollar affair on a daily basis. But the Fed’s repos are only being nibbled on every now and then. What’s left on the Fed’s balance sheet are several term-repos from weeks ago. Repos are in-and-out transactions. When repos mature, the Fed gets its cash back, the counterparty gets its securities back, and the repo balance for that entry goes to zero.

There are $158 billion in repos left on the balance sheet. I’ve dug up most of them. Over the next two months, they will all mature and roll off the balance sheet:

- From April 29: $2.0 billion, 1-day

- From April 13: $14.5 billion, 28-day

- From April 6: $6.3 billion, 28-day

- From April 3: $1 billion, 84-day

- From March 20: $31.2 billion, 84-day

- From March 13: $17.0 billion, 84-day

- From March 12: $78.4 billion, 84 day

Total repo balance, at $158 million, is down 64% from the peak ($442 billion):

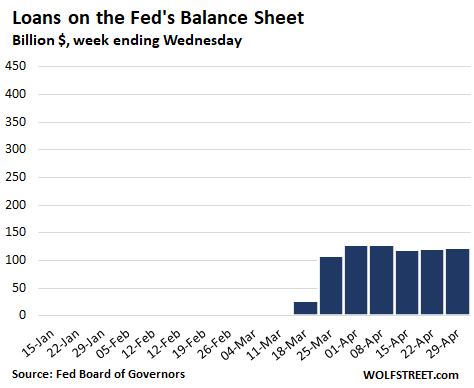

“Loans” to SPVs & Primary Dealers went nowhere in five weeks.

The Fed’s alphabet soup of bailout programs are in effect loans to Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) that the Fed has set up in conjunction with the US Treasury Department, and to its Primary Dealers (the big broker-dealers and banks the Fed does business with). The Fed in essence lends to them, and they can buy whatever the Fed directs them to buy or lend to entities the Fed directs them to lend to.

This scheme is a way to get around the limits imposed on the Fed by the Federal Reserve Act. Congress could stop these schemes but applauds them.

When the Fed announced the first batch of its alphabet soup of bailout programs, “loans” on its balance sheet ballooned. But over the five weeks since then, they have remained essentially flat at around $122 billion:

The Fed shows these loans by category:

Primary credit: fell to $32 billion, from $34 billion last week and from $43 billion three weeks ago. This SPV was expanded to be able to buy some “fallen angel” junk bonds. But the balance has dropped since the expansion and the Fed hasn’t bought any fallen-angel junk bonds. Some of the positions have unwound, and the SPV paid the associated loans back to the Fed.

Secondary credit: $0. Designed to purchase corporate bonds, bond ETFs, and even junk-bond ETFs. None were purchased.

Seasonal credit: $0

Primary Dealer Credit Facility: fell to $25 billion, from $36 billion two weeks earlier. Amounts the Fed lent to primary dealers to buy stuff with. After the initial burst, some of the positions have been unwound, and the loans were paid back.

Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility: fell to $46 billion, from $49 billion last week, and from $53 billion three weeks ago. This SPV bought corporate paper and other short-term assets to bail out money-market funds. After the initial burst, the positions have started to unwind, and the SPV paid back some of the loans.

Paycheck Protection Program Liquidity Facility: Jumped to $19 billion from $8 billion. This is where the Fed lends to the SPV to buy from the banks the government-guaranteed loans they have issued to “small businesses” (hahahaha) under the PPP program. This SPV does nothing for small businesses. It just takes some loans off the books of the banks after they’ve extracted their fees for processing the PPP loans.

These loans show that the Fed has not done any of the things with SPVs and Primary Dealers over the past five weeks that the markets were drooling and raving about – they didn’t buy junk bonds, ETFs, or stocks. The markets just haven’t figured it out yet.

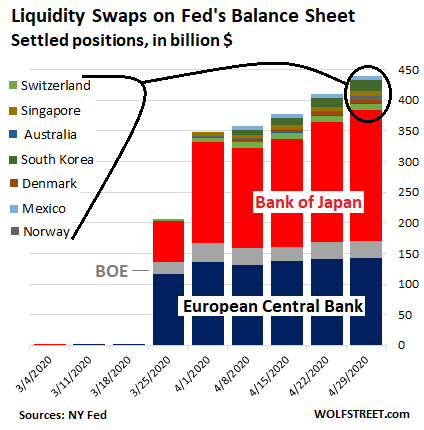

Central Bank Liquidity Swaps.

The Bank of Japan is by far the biggest user of the Fed’s “dollar liquidity swap lines.” Swaps with the BOJ surged by $18 billion from the prior week to $214 billion and now account for 49% of the total swaps on the Fed’s balance sheet.

The ECB is the second largest user of the swap lines, with balance of $142 billion, 32% of the total. The Bank of England is far behind with $28 billion.

The Fed also has opened swap lines with the central banks of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Switzerland, Singapore, South Korea, Brazil, and Mexico. There are no swaps with the central banks of Canada, Brazil, New Zealand, and Sweden. And the remaining central banks are small fry (see chart below).

With these swaps – maturities of either 7 days or 84 days – the Fed lends newly created dollars to another central bank, against domestic currency posted at the Fed as collateral. The exchange rate is the market rate at the time of the contract. When the swaps mature, the Fed gets its dollars back, and the other central bank gets its own currency back.

The combined amount of those swaps – the country data is released by the New York Fed – increased by $29 billion from the prior week to $439 billion.

If…

Since March 11, the Fed has printed $2.34 trillion to inflate asset prices, restart the chase for yield to where investors would lend to companies with deep-junk credit ratings, already too much debt, and business models that have run aground. It did so to bail out asset holders and Wall Street.

If the Fed had spread that $2.34 trillion equally over the 130 million households in the US, each household would have received $18,031. For many households, this would have gone a long way to helping them through the crisis. But this was helicopter money for Wall Street.