Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, http://www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

Today’s rate hike by the central bank of Sweden ends an absurdity. ECB and other central banks with negative rates are getting ready to follow.

The central bank of Sweden, the Riksbank, has thrown in the towel on negative interest rates, and has become the first central bank in history to do so. At its meeting on October 24, it said that it would “probably” do so, after already suggesting at its September meeting that it would do so. And today, it did so. It announced that it raised its “repo” rate to 0%.

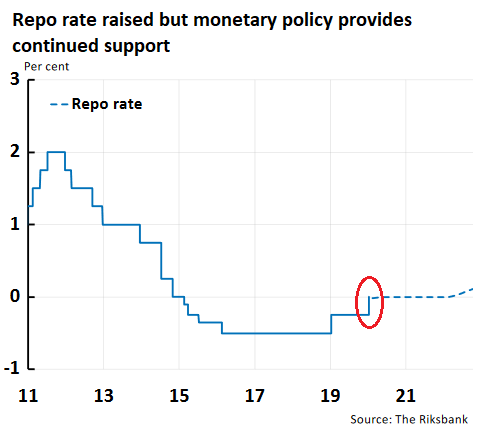

It wasn’t exactly a heroic move, but it was the first time in history that a central bank that had gone full NIRP, and had done so before most others in early 2015, has exited it. The new repo rate will be effective January 8. Chart via the Riksbank’s presentation materials. I circled today’s decision:

All options are on the table: “Improved prospects would justify a higher interest rate. But if the economy were instead to develop more weakly than forecast, the Executive Board could both cut the repo rate and take other measures to make monetary policy more expansionary.”

But it’s not getting out of NIRP because the economy is running red-hot. On the contrary. The statement:

Similar to economies abroad, the Swedish economy has entered a phase with lower growth. However, the slowdown is occurring after several years of high growth and strong developments on the labor market, and overall it means that the Swedish economy is going from a stronger-than-normal cycle to a more normal situation.

Inflation has been close to 2 per cent since the beginning of 2017. After an expected decline over the summer, it has once again risen to just under 2 per cent.

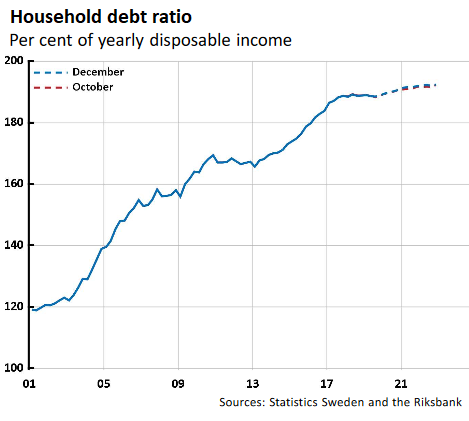

One of the motives for raising its repo rate out of the negative is visible in its warning about household indebtedness which is among the highest in the world – with household debt exceeding 190% of disposable income — in part due to the low and negative interest rate environment that caused Swedes, as would be expected, to borrow with reckless abandon. The chart (via the Riksbank) includes the Riksbank’s forecast that household indebtedness will continue to rise, though it has started to dip just a tiny little bit:

The Riksbank suggested the government should take measures to tamp down on this reckless abandon and its impact on the inflated housing market:

Swedish households are heavily indebted and thereby sensitive to changes in economic conditions. In order to reduce the risks linked to household indebtedness and address the structural problems on the Swedish housing market, measures within housing and tax policy and appropriate macroprudential policy are required.

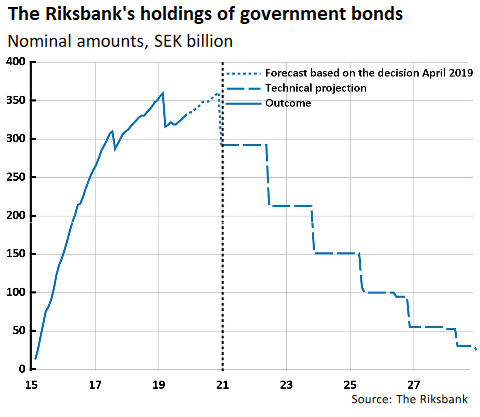

QE continues but at a fraction of its former rate. The Riksbank forecasts that it would end QE entirely in 2020 and start unwinding its positions and reduce its balance sheet in 2021 until all its QE government bond holdings have disappeared from it by around 2030. The chart below shows the “forecast” through 2000, and at the beginning of 2021, at the dotted vertical line, its forecast turns into a “technical projection”:

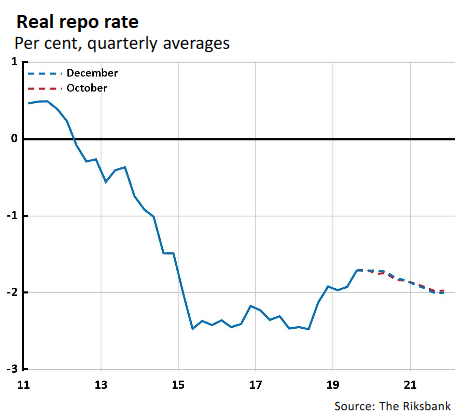

And it also pointed out the “real repo rate” – the repo rate minus the inflation rate as measured by CPI – was still steeply negative at near -2.0% and would remain so, brutal financial repression still being the rule:

The Riksbank isn’t exactly the largest central bank with negative interest rates; those are the ECB and the Bank of Japan. The ECB is now undertaking a “policy review,” to determine how it wants to move forward. It is facing a wall of resistance against negative interest rates among the finance ministers of Eurozone member states because of the damage negative interest rates do to the banking system and pension funds, and because of the housing bubbles they’re now creating. Among ECB governors, the wave of resistance against negative interest rates has already boiled over the top when Draghi was still running the show. And the ECB’s policy review will likely produce a NIRP-exit strategy. But little Sweden has led the way.

Canada’s “high household debt load is the most important risk facing the financial system,” said the governor of the Bank of Canada. But it’s complicated. Read… The State of the Canadian Debt Slaves, How They Compare to American Debt Slaves, and the Bank of Canada’s Response