Banks are trying, but demand just isn’t there.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

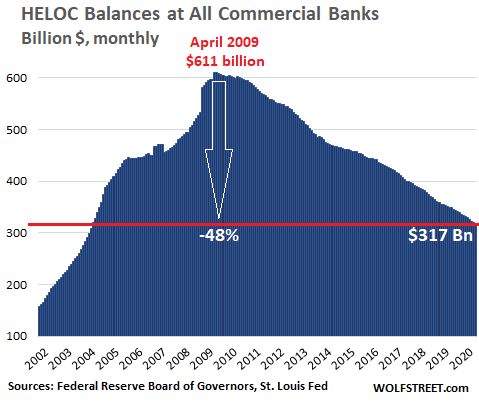

At the end of January, outstanding balances of homeowner lines of credit (HELOC) at all commercial banks in the US – not including nonbanks, or “shadow banks,” we’ll get to those in a moment – fell to $317 billion, according to the data released on Friday by the Federal Reserve Board of Governors. They’ve plunged 48% from the peak in April 2009 and are now back where they’d been in April 2004. These are the balances that are actually outstanding and do not include the unused portion of the credit line:

Banks and nonbanks have been trying to get homeowners to take out HELOCs, which are credit lines secured by the home, and risks for lenders are lower than with credit cards because in case of a default, they can go after the home. Credit cards are unsecured.

For homeowners, HELOCs fill a similar function as a credit card, but borrowing costs are lower. And like a credit card, the rate is usually variable. HELOCs played a role during the mortgage crisis that triggered the Global Financial Crisis. But things are different now, and banks and shadow banks want Americans to borrow in this manner and spend the money on vacations or home improvements or a new car, or whatever. Google them and see how they’re trying.

And the Fed, which tracks these HELOC balances at the commercial banks it regulates, wants homeowners to borrow against the rising values of their homes and splurge with this money and thereby convert inflated home prices into retail sales and consumer spending and thereby into GDP growth, and into additional interest income.

When William Dudley was still president of the New York Fed, he addressed this refusal by households to do so. In a speech, he lamented this “change in household behavior” – that households have refused to turn home equity into retail sales and GDP growth, after getting burned during the mortgage crisis for having done the same. And the situation, from the Fed’s point of view, has gotten more dire.

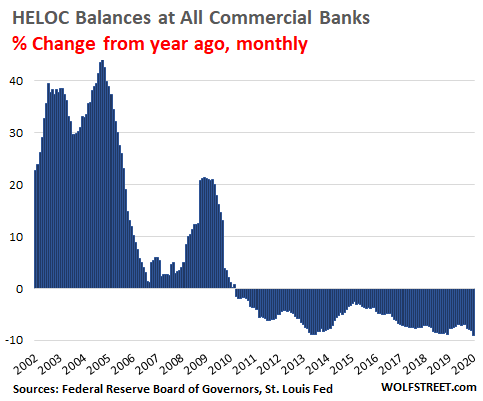

In January, HELOC balances at all commercial banks dropped 9% from January last year, the steepest year-over-year percentage decline since 2013. This chart shows the relentless year-over-year declines of HELOC balances:

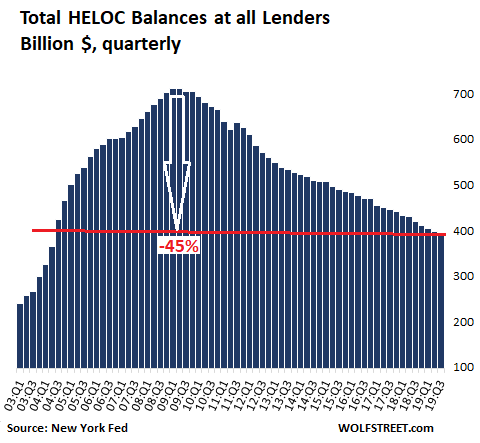

These are the HELOC balances at all commercial banks, tracked by the Fed’s Board of Governors, but do not include the balances at nonbanks, which are not regulated by the Fed. On the other hand, the New York Fed releases data on total household credit balances at all lenders, including nonbanks, on a quarterly basis. Its latest release (for Q3) shows a similar trend.

Total HELOC balances at all lenders, including nonbanks, plunged 45% from $714 billion in Q1 2009 to $396 billion in Q3 2019:

So what is going on here?

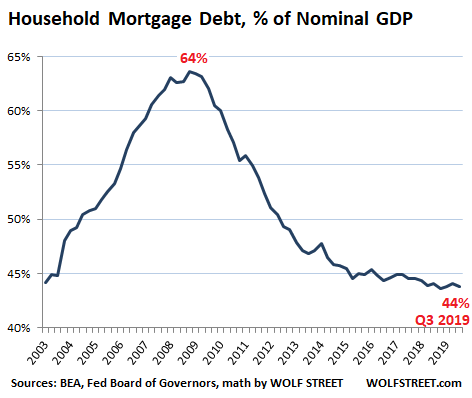

Housing-related debt fell off sharply during and after the mortgage crisis as foreclosures made their way through the system: Total housing debt had peaked at $9.99 trillion in Q3 2008, and then dropped by 16% to $8.4 trillion. In Q3 2019, it almost got back to where it had been in 2008, to $9.83 trillion.

But there are now 128.6 million households, up 9% from the 116.8 million households in 2008. Everything has grown over the 11 years, the economy, the population, incomes, consumer prices, and home prices. So the current housing debt in aggregate, compared the overall economy, has fallen from 64% of nominal GDP at the peak, to 44% in Q3 2019.

So “in aggregate,” this looks good. But this aggregate is composed of several opposing factors, including these four:

- Many homeowners have paid off their mortgages and own their homes free and clear, which has become a more attractive option for households in expensive housing markets, as the mortgage interest deduction has been further reduced, and as “risk-free” returns (Treasury securities, FDIC insured CDs, etc.) have been miserably low.

- Many other homeowners are pushing the envelope in terms of their mortgage debt and mortgage payments, struggling to make ends meet on a monthly basis. If one of the earners loses their job, the entire math gets in trouble.

- Cash-out refis have become popular again, and the risks associated with them are increasing to where regulators are trying to put some limits on them, but in terms of the mortgage debt “in aggregate,” they have not moved the needle much.

- The homeownership rate has declined from 69% in 2005-2006 to 65.1% currently, after hitting a multi-decade low of 62.9% in 2016. This means fewer mortgages and fewer HELOCs and more renters.

HELOCs are viable credit tools for homeowners, if used prudently. If not used prudently, they can contribute to a mortgage meltdown and foreclosure.

Since HELOCs are secured by the home, a default on the HELOC can trigger a foreclosure. With credit cards, this cannot happen, though the bank can sue and try to recover its loss that way.

The unused portion of a HELOC may not necessarily be there when you need it the most as the bank can freeze the HELOC when the price of the home drops, and not allow you to dip into it further. Suddenly, your credit line that you relied on is gone.

During the past housing bust, HELOCs were big contributors to homeowners being underwater with their mortgages. When homeowners could no longer make the payment, they then found out that they couldn’t sell the home either, and that foreclosure was at the end of that tunnel. And this experience is still in the collective memory of homeowners.