Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, http://www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

Inflation runs hot in housing, medical services, health insurance, other items that are not imported.

The consumer price inflation data released today by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which corroborates prior inflation data, says that, yes, prices are rising, but they’re rising sharply in services that are not impacted by imports and tariffs, such as rents and other housing costs, healthcare, education, and other services, and also in restaurants (where customers pay mostly for labor and rent). But inflation in durable goods, such as electronics, cars, and the like – where the tariffs would show up – was very low.

Inflation as measure by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose 0.3% in July from June and 1.8% over the 12-month period. This was largely held down by a decline in energy costs (-2.0% due to the ongoing oil bust) and by a very slow rise in the costs of durable goods.

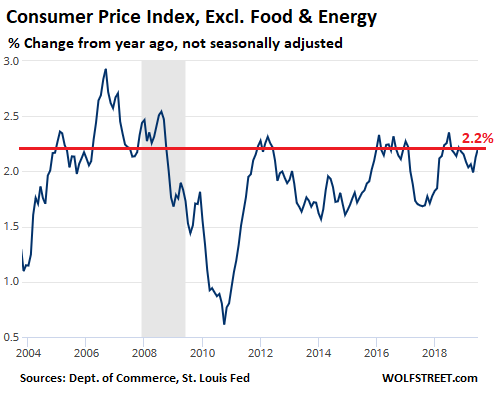

Food and energy prices are very volatile, dancing to the tune of oil busts, droughts, floods, diseases in animals, and other factors. Together, they weigh about 21% in the overall CPI. A less volatile measure is the CPI without food and energy, or “core CPI,” which rose 2.2% over the 12-month period, at the high end of the 10-year range:

Where does this inflation come from?

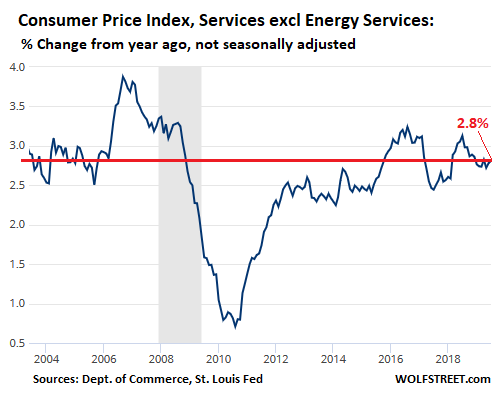

Primarily Services: Services include the biggies that consumers spend most of their money on: housing costs, healthcare, financial services, telecommunications services, education, etc. Services without energy services (such as utilities) weigh about 60% in the overall CPI. These services have nothing to do with imports or tariffs, and over the 12-month period, their prices jumped 2.8%:

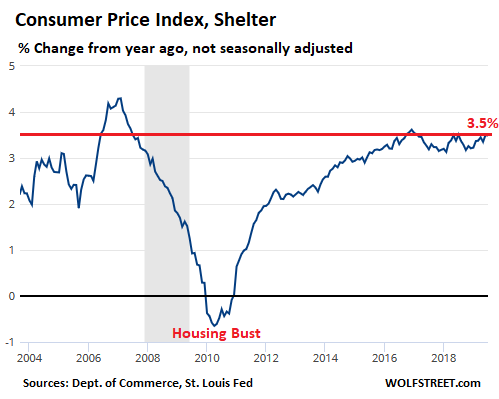

“Shelter,” the biggie, accounts for 33% of the overall CPI. “Shelter” is a group of services that includes housing costs, such as rents and “owner’s equivalent of rent” (what it would cost a homeowner to rent the home), plus hotels, and the like. Shelter has nothing to do with imports or tariffs, and it jumped 3.5% over the 12-month period, at the very top of the 10-year range:

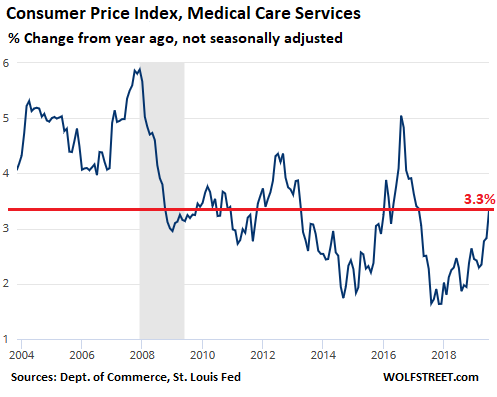

Medical care services, the second largest group in services, account for about 7% of total CPI. This does not include pharmaceutical products, but includes hospital services, dental services, and the like. And it includes health insurance, which – as we guessed with our grin-and-bear-it grimace – soared 15.9% over the 12-month period, driving prices of total medical services up by 3.3%:

Where does this inflation not come from?

Durable Goods – products like cars, furniture, appliances, TVs, smartphones, computers, tools, lawnmowers, etc. A lot of products in this category are imported, or even if the products are “made” in the US, their components are imported. This is where tariffs would hit the hardest.

A reminder what inflation is and is not. Inflation is a price increase of the same item with the same qualities and features, and the same quantity or size. If new cars get better – improved safety features, performance, electronics, etc. – this cost of the improvements shows up in a higher price of the car, but is removed from the inflation data. Same with smartphones, and other products. A $800 laptop today is a thousand times more powerful and feature-laden than a laptop in 1995 that cost $2,400.

Many durable goods are far better than they were, but cost less, such as laptops. Other products cost more, but you’re getting a better product. Your cost of living goes up because you buy those improved products, and because you buy products that didn’t exist before, such as smartphones. In return, you’re presumably safer and more comfortable and better connected and get better quality of life of whatever. That’s the theory. Inflation is when the same thing with the same qualities gets more expensive.

By this measure, deflation in durable goods has long been common. As manufacturing (automation) and transportation get more efficient, the same products should cost less. Globalization of manufacturing has contributed to that, as US companies offshored production to cheap countries.

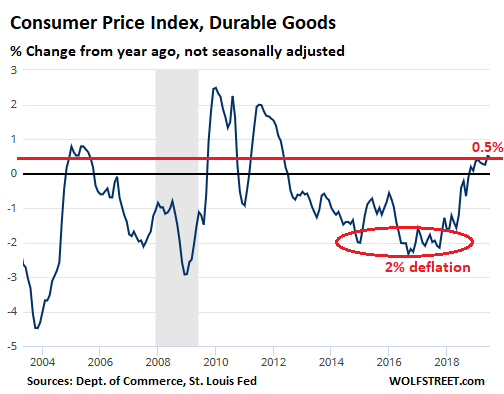

The Consumer Price Index for durable goods inched up 0.5% in July, compared to a year ago (and a slightly slower rate than the year-over-year increase in June). In the Fed’s eyes, while an improvement over the -2% range (deflation) in 2016 and 2017, it was still insufferably low inflation. Some upward pressure in prices of durable goods – tariffs or no tariffs – would bring the Fed to its goal, and it can get off its “low inflation” bandwagon. But we’re not there yet:

Corporate America, focused on offshoring production, hates tariffs. Foreign companies, focused on sending their goods to the US, also hate tariffs. They’re first in line to pay for the tariffs. Their hope is that they can pass them on to consumers. But they’re having trouble doing so.

Consumer prices in the US are not set by companies but by the market (unless there is a monopoly or a screwed-up situation as in healthcare where there is no market). Walmart might want to raise the prices of its Chinese stuff, but consumers can buy this stuff elsewhere, and they can dig up the lowest price on the internet. This causes Walmart to lose a sale. Price increases in goods that can be comparison-shopped over the internet have had a very hard time sticking.

Corporate America just received a large income-tax cut. And companies didn’t pass those tax cuts on to consumers. Tariffs are the opposite, but on a smaller scale: They’re a tax increase on corporations, both US importers and foreign companies exporting to the US. But they impact profit margins on sales, rather than taxable income.

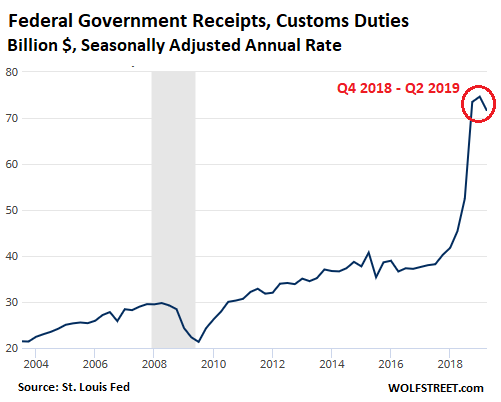

If in the future foreign and US companies are finally able to raise prices on durable goods – tariffs or no tariffs – and make them stick, it might finally cause the Fed to get off its “low inflation” bandwagon and declare that long-sought-after “victory” of having met or exceeded its target. Meanwhile, these tariffs bring in big revenues to the US government, having doubled from prior years to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of over $70 billion, and the government sure needs that moolah:

In the US alone, “Financial Repression” impacts nearly $40 trillion — with consequences for the real economy. Read… The Giant Sucking Sound of Financial Repression