Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, http://www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

“Sell first, ask questions later.”

The $1.2-trillion US leveraged loan market is starting to get downgrade-indigestion. So far this year through October 11, of the 1,460 leveraged loans in the S&P/LSTA Index, 282 issues were downgraded, already exceeding the 244 downgrades for the entire year of 2018, and blowing past the 33 downgrades in 2017, according to LCD of S&P Global Market Intelligence.

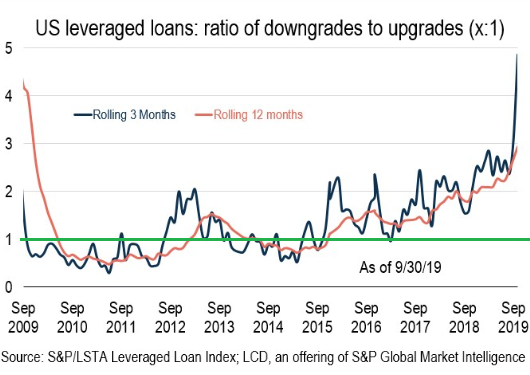

On a rolling three-month basis, the ratio of downgrades-to-upgrades spiked to 4.9, by far the highest ratio since the Financial Crisis. In the chart below via LCD, a value greater than 1 (horizontal green line) means downgrades exceed upgrades. A value blow 1 means upgrades exceed downgrades.

Collateralized Loan Obligations get cold feet.

The hot-button issue at the moment with leveraged loans is a one-step downgrade from B-, or a 2-step downgrade from B (“highly speculative”), to triple-C (“substantial risk,” see my cheat sheet for corporate bond and loan credit ratings by ratings agency).

It’s a hot-button issue because managers of Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLOs) currently purchase about three-quarters of the leveraged loans that banks are syndicating and hold about 55% to 60% of all leveraged loans outstanding, according to LCD. But CLOs have limits as to how much in CCC-or-below-rated loans they can hold.

The majority of CLOs limit their holdings of triple-C or below rated loans to 7.5% of their portfolio. According to LCD, the median share of these loans within US CLOs is currently 4.1%, meaning half of the CLO’s already have over 4.1% of these loans in their portfolio, and they need to keep some room available when their single-B rated loans get downgraded to triple-C.

So when loans are downgraded to triple-C, and the CLO buckets for loans with this rating are full, then suddenly buyers are difficult to find, and funding threatens to dry up for these companies, which can push them into bankruptcy. In addition, banks can get stuck with leveraged loans. Both of which are already happening.

Leveraged loans are typically junk-rated loans issued by companies that have too much debt and not enough cash flow. Banks have no intention of hanging on to these loans. Instead, they plan to offload them to CLOs, loan funds, and other investors.

But some banks are getting stuck with the loans.

Investment banks – including Jeffries, UBS, Barclays, Deutsche Bank – have recently gotten stuck holding at least seven leveraged loans, totaling about $2 billion, sources told Bloomberg. These loans were used to fund acquisitions, including the leveraged buyout of Shutterfly by private-equity firm Apollo Global Management.

The banks could not off-load these loans for now and remain on the hook. While the amount is still relatively small, given the size of the leveraged loan market, this – and the stress showing up with single-B rated loans – is happening when yield-starved investors are otherwise still exuberant. Bloomberg:

Worries over a potential downturn have reduced demand for lower-rated loans at risk of downgrades, especially from collateralized loan obligations, which face limits on the amount of debt rated in the weakest CCC tier that they can own.

So CLOs are crucial in getting these loans off the banks’ books. Now all eyes are on the single-B category (B+, B, B-) that makes up 56% of all US leveraged loans outstanding. Loans rated B- account for about 13% of US leveraged loans outstanding, nearly double from early 2017. They’re just one notch away from CCC+.

This limit of 7.5% for triple-C or below rated loans is not a hard limit. Various factors allow a CLO to hold up to 12% of its portfolio in these loans, according estimates by Wells Fargo analysts cited by LCD.

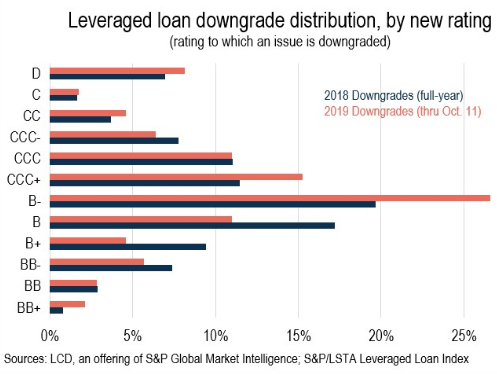

Of the 282 downgrades this year so far, 27% were downgraded to B- and 15% were downgraded to CCC+. The chart below shows the distribution of downgrades in 2019 so far (orange bars) and in all of 2018 (blue bars). “D” stands for “default.” BB+ is one step below investment grade. Note this year’s surge in downgrades to B- and CCC+ compared to last year:

“Sell first, ask questions later,” that’s the current attitude in the market about loans rated B-, LCD says:

CLO managers, however, are not waiting for rating agencies to act. Instead, they’re looking to get out in front of any earnings miss, especially as managers find liquidity disappearing quickly on a number of names.

Double-B rated loans “remain well bid,” according to LCD. The loans that are held by CLOs and that selling off are single-B, and they’re selling off out of fear of a downgrade to triple-C:

- The portion of these loans that are trading for less than 90 cents on the dollar has reached 9.5% of all loans held by CLOs, up from 6.5% in August.

- The portion of these loans trading for 80 cents on the dollar has doubled to 4%, from 2% in August.

For example, Deluxe Entertainment Services Group’s $782-million leveraged loan was trading at around 90 cents on the dollar in July. In August, a proposed spinoff and equity infusion didn’t pan out as planned, which led S&P to down grade the loan from B- to CCC-. The loan plunged to a range between 36 and 40 cents on the dollar, according to LCD. Then this happened:

The credit is held by a number of CLO managers, many of whom were unwilling to participate in additional financing for the company following the downgrade, as they were hesitant to double down on additional CCC exposure at this stage.

As these existing investors – the CLO managers – were not able or willing to provide additional financing needed to keep the company afloat, Deluxe filed for a pre-packaged Chapter 11 bankruptcy and then obtained a Debtor in Possession (DIP) loan. Its $782-million leveraged loan last traded at about 5 cents on the dollar, according to LCD.

That’s how a downgrade from single-B to triple-C can push a company over the edge because it can get cut off from funding.

The industry is now wondering, with CLOs being limited as to the amount of triple-C loans they are able or are willing to buy, who will buy them? There will be buyers, including funds set up specifically to buy distressed credits – if the price is low enough. But that price may be so low – and the yield so high – that it effectively cuts off the company from any funding and pushes it into bankruptcy court.