This is the moment when yield-chasing turns into a massacre.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET:

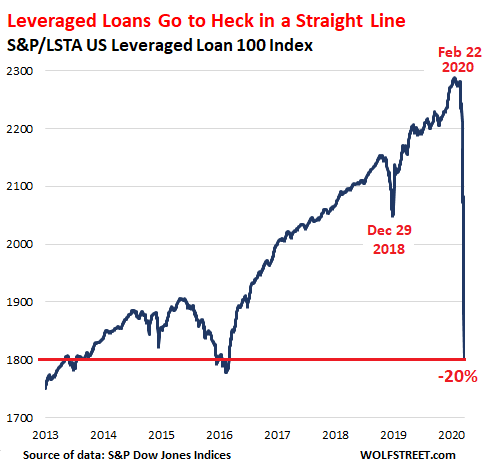

Leveraged loans – they’re issued by junk-rated overleveraged companies with insufficient cash flows – are part of the gigantic pile of risky corporate debt that is now being brutally repriced as concerns over credit risk (the risk of default) are finally bubbling to the surface. Since February 22, the S&P/LSTA US Leveraged Loan 100 Index, which tracks the prices of the largest leveraged loans, has plunged 20%:

The index is another example of how in these crazy times, when the most splendid Everything Bubble collided with the coronavirus, ever more financial metrics are violating the WOLF STREET beer mug dictum that “Nothing Goes to Heck in a Straight Line.”

Leveraged loans are risky and murky. And they’re a big pile: about $1.2 trillion of US-originated leveraged loans, up 50% from $800 billion in 2015. These loans are traded in slices like securities or are packaged into highly rated Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLOs). But for years, investors had the hots for them, driven by their relentless chase for yield, in a world of interest rate repression.

These companies are often owned by private equity firms that had acquired them through leveraged buyouts, during the process of which they loaded up the companies with debt. In addition, PE firms extracted special dividends from their companies, funded by leveraged loans, which is a form of asset stripping. This leaves the company more leveraged and more precarious and more likely to topple. But who cares? Those were the good times and the chase for yield was on.

The Fed, the Bank of England, the ECB, the Bank of Japan, etc., they have all warned about leveraged loans. But they don’t regulate them because central banks are not securities regulators. And securities regulators, such as the SEC, consider them loans and not securities, and they don’t regulate them either. And no one knows into whose balance sheets leveraged loans can blow holes. But now they’re blowing holes into balance sheets.

Leveraged loans that trade below 80 cents on the dollar are considered “distressed” – and now 38% of the leveraged loans trade below that distressed level, up from 10% on March 13, and up from 2% a year ago, according to LCD by S&P Global:

During the peak of the 2008-2009 Financial Crisis, 81% of loans were priced below the 80 level. At the current rate of progress, the leveraged loan market will soon catch up with it. But as LCD notes, the magnitude is different:

Back then, there were only $583 billion of leveraged loans outstanding; with 81% of them trading at distressed levels, there were $472 billion in distressed loans.

Now, there are about $1.2 trillion in leveraged loans outstanding; with 38% of them trading at distressed levels, there are $446 billion in distressed loans – nearly the same as during Financial Crisis 1, but we’re just a few weeks into it.

And LCD reported that the average bid of the S&P/LSTA Leveraged Loan Index had plunged to just 78.36 cents on the dollar at Friday’s close.

These are the 10 most distressed sectors by the percentage of loans that trade below 80 cents on the dollar as of Friday at the close – and given the current mess, there are not a lot of surprises on this list:

- Air transport (98%)

- Oil and gas (81%)

- Brick & mortar retailers (75%)

- Aerospace and defense (69%)

- Leisure (68%)

- Hotels, motels, casinos (68%)

- Nonferrous metals and minerals (62%)

- Automotive (58%)

- Chemicals, plastics (44%)

- Beverage and tobacco (43%)

And over the five trading days ended March 18, these were the top losers by sector, in terms of price drops of their leveraged loans, according to LCD:

- Air transport: -15.4%

- Oil & Gas: -15.2%

- Lodging & casinos -14.5%

- Movies, Leisure goods, activities: -14.2%

- Nonferrous metals and minerals: -14.2%

Companies whose loans trade at distressed levels have a very difficult time borrowing new money to meet their cash flow needs, pay interest, and pay off maturing debts. But these companies have cash flows that are not adequate to service their debts – which is one of the reasons they’re junk-rated in the first place.

And when corporate debt blows up, it has an immediate impact on the real economy: At that point, these companies have to restructure their debts either in bankruptcy court or outside of it, which nearly always leads to layoffs, cost cuts, and slashed capital expenditures, which then ripple through the rest of the economy, thereby acerbating the downturn.

The Fed has pointed out this risk in its financial stability reports. But instead of tamping down on rampant yield chasing and on the corporate debt bubble by raising short-term rates to something like two percentage points above the rate of inflation by 2015 and unloading the pile of securities on its balance sheet to bring up long-term rates, the Fed further encouraged it all with its loosey-goosey monetary policies. So now here we go again.