Authored by Andrew Sheets, chief cross-asset strategist at Morgan Stanley

Over recent weeks, you’ve heard us discussing why we think investors should fade the optimism from the recent G20. Why we think bad data should be feared rather than cheered because it will bring more central bank easing. Why we think the market is too optimistic on 2019 earnings and is underestimating the pressure from inventories, labour costs and trade uncertainty.

The time has come to put our money where our mouth is. In light of these concerns and others, we are downgrading our allocation to global equities from equal-weight to underweight.

The most straightforward reason for this shift is simple – we project poor returns: Over the next 12 months, there is now just 1% average upside to Morgan Stanley’s price targets for the S&P 500, MSCI Europe, MSCI EM and Topix Japan (including dividends and equally weighted). If we ignore those targets and estimate returns for those same regions based on current valuations, adjusting for whether returns tend to be better or worse given current economic data, the upside is very similar (3%). There comes a point for every analyst where you need to change your forecast or change your view. We’re doing the latter.

Why are those return estimates so low, especially in light of possible central bank easing? Our economists, after all, are calling for the Federal Reserve to lower rates later this month, and the ECB to embark on a new round of quantitative easing.

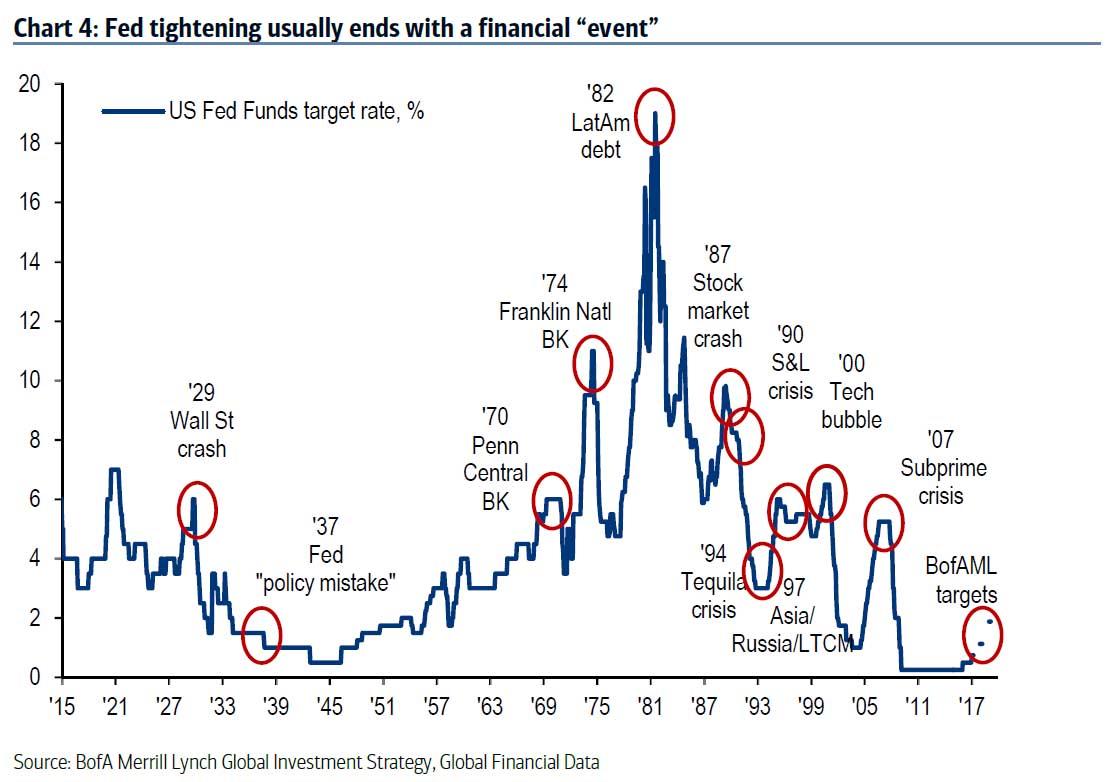

Our concern is that the positives of easier policy will be offset by the negatives of weaker growth: We think a repeated lesson for stocks over the last 30 years has been that when easier policy collides with weaker growth, the latter usually matters more for returns. Easing has worked best when accompanied by improving data. If you don’t believe us, we have some European stocks from April 2015, shortly after the ECB’s first QE programme was announced, that we’d like to sell you.

As markets have rallied over the last month, global trade and PMI data have continued to worsen. Global inflation expectations, commodity prices and long-end yields suggest little optimism about a growth recovery. On the back of the G20, our economists downgraded their global growth forecasts. We forecast an aggressive Fed and ECB action because we think growth concerns are material.

Given our disagreement on how much policy easing will help, it’s reasonable to ask: Why not make this change in August, after the Fed cuts? Because we do see two potential nearer-term catalysts: 2Q earnings season and the drop in summer liquidity.

On earnings, we think the market is underpricing the risk that companies lower full-year guidance. Just think about how much has changed since 1Q reporting in mid-April:

- A US-China trade deal that was widely expected to be resolved led instead to a new round of tariffs.

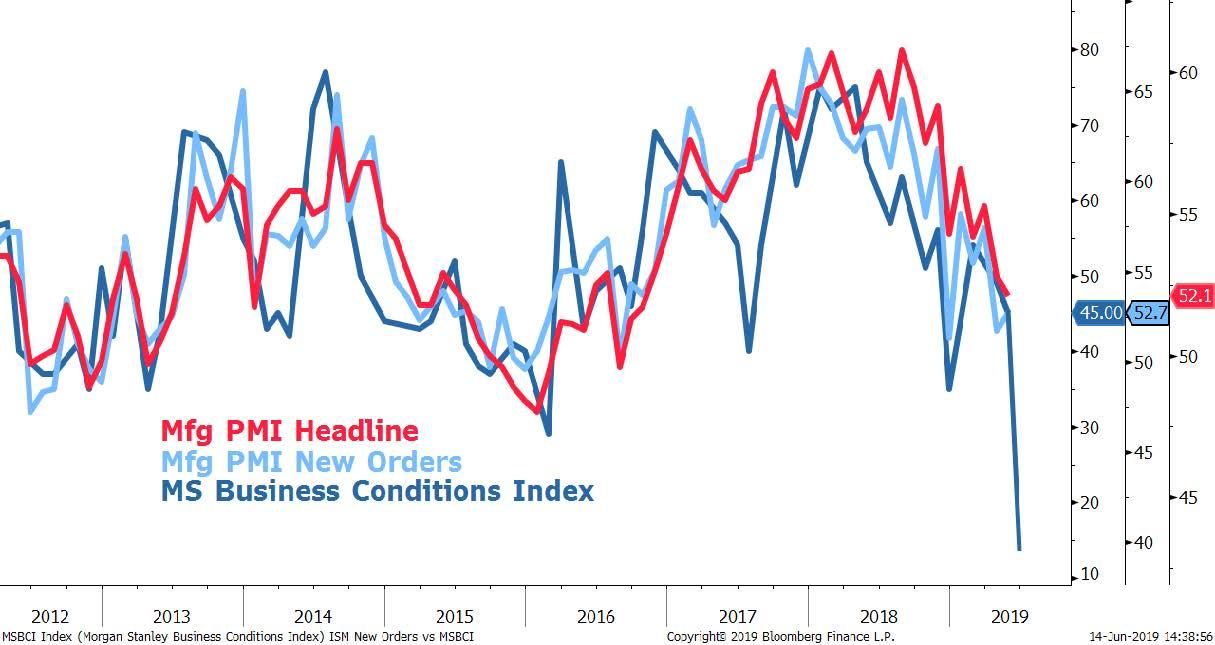

- Global PMIs have continued to fall.

- And Morgan Stanley’s Business Conditions Index, a survey of how our equity analysts feel about their companies, suffered its largest one-month decline ever in June. We believe all this signals risk to equities.

Meanwhile, we’re mindful of the drop in both liquidity and average returns starting in late July. For trivia fans out there, July 13-October 12 has historically been the worst 90-day period for equity returns since 1990, possibly because liquidity and risk appetite tend to worsen after 2Q results. And given high expectations of central bank easing, and a number of geopolitical uncertainties, the risk that poor liquidity magnifies bad news seems credible.

What about ‘TINA’ and the lack of investor euphoria? The idea that ‘there is no alternative’ to stocks, given richness in other asset classes, is one of the most frequently cited reasons to be positive (along with central bank support). Meanwhile, it’s equally fair to say that measures of investor sentiment don’t look excessive.

Relative to bonds, stocks do offer a historically elevated equity risk premium (ERP). But we think it’s dangerous to be too sanguine about both these supports. ERP is a valuation measure, and like all such measures it is much better as a multi-year guide than a near-term indicator, being easily swamped by more pressing concerns. Stocks have looked cheap to bonds for almost the entire post-crisis period. That didn’t prevent a number of meaningful drawdowns.

If investors really believe in the power of ‘cheapness to bonds’ they have an odd way of showing it. Europe, Japan, Value and Cyclicals are the segments of the market cheapest to fixed income. They are also the least-loved. Indeed, while investor positioning may not be particularly extended overall, it looks relatively concentrated in the US, Growth, Quality and Defensives.

This bull market, which started in 2009, has repeatedly defied all manner of doubts. There are many ways we could be wrong, but the greatest risk, in our view, is that the growth data bounce but central banks still follow through with aggressive easing. Such a scenario would likely see a bear steepening of the yield curve, higher inflation expectations and higher commodity prices. We’ll watch for those as signs that we need to make a change.

For now, we’re putting our money where our mouth is. Following these changes, we are underweight both equities and credit, equal-weight government bonds and overweight cash. Our most preferred asset class remains emerging market fixed income.