Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, http://www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

During the selloff in December, the BOJ shed $31 billion, but in January it piled on.

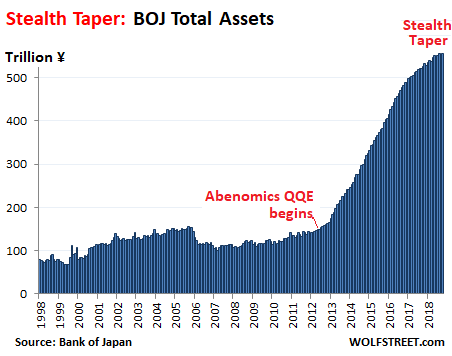

Total assets on the Bank of Japan’s mammoth balance sheet, after a drop of ¥3.4 trillion ($31 billion) in December, rose by ¥4.8 trillion ($44 billion) in January, to ¥557 trillion ($5.1 trillion), the BOJ reported this morning. This shows two things:

One: The balance sheet is now 101.5% of Japan’s nominal GDP (¥549 trillion, not adjusted for inflation), which makes it over five times as large in terms of the economy as the Fed’s $4-trillion balance sheet, amounting to 19.6% of US nominal GDP ($20.6 trillion). This is how crazy the situation at the BOJ has become:

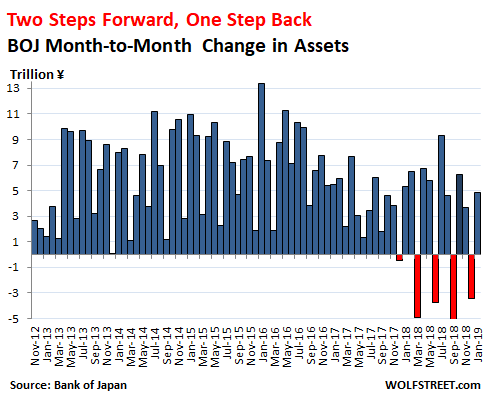

Two: The BOJ is now proceeding with its QQE – “quantitative and qualitative easing,” as it calls this monster – in a special sort of dance: Two steps forward, one step back – increasing its balance sheet two months in a row, then in the third month unwinding about one-third of the increase of the prior two months.

This dance series started in December 2017. December 2018 had been the fifth step back. And January was the next step forward. Among QE-besotted central banks, this dance is unique. This chart shows the month-to-month changes of the balance sheet. Note that the December “step back” was maintained despite the selloff in the markets:

The above chart shows that last December, the BOJ cut its balance sheet by ¥3.4 trillion ($31 billion), a larger cut than the Fed’s QE unwind in December($28 billion). In September, the BOJ chopped its balance sheet by ¥5.4 trillion ($49 billion), larger than the Fed’s QE unwind in September ($34 billion). The prior two balance sheet cuts (March and June) were also larger than the Fed’s QE unwind during those months.

And each of the BOJ’s reductions undid between 30% (June 2018) and 42% (March 2018) of the prior two months’ increases.

The switch from regular QQE to the two-steps-forward-one-step-back QQE came without any announcement from the BOJ, which continues to say that “QQE with yield curve control” – the BOJ is targeting the entire yield curve, not just short-term yields – will be maintained for as long as needed to achieve 2% inflation.

It did add a couple of rubbery terms in its minutes of the July 2018 meeting: “sustainability” and “flexibility” of QQE. According to the minutes, the BOJ’s staff “proposed measures to enhance the sustainability of the current monetary easing” given, “for example, their effects on financial markets.” And the minutes also said that the BOJ would buy Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) in “a flexible manner.”

But the minutes reiterated that the BOJ would increase its holdings of JGBs by about ¥80 trillion a year, which the BOJ has not come anywhere near since 2016, as we’ll see in a moment.

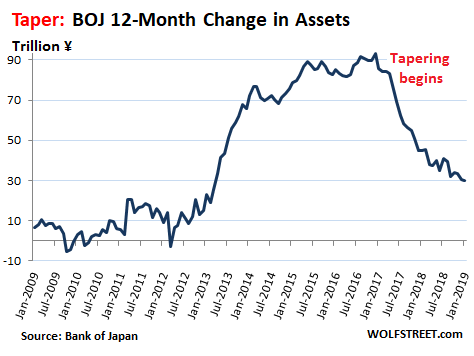

QQE started in December 2012 as part of Abenomics. During peak QQE, in the 12-month period ended December 31, 2016, the BOJ’s assets ballooned by ¥93.4 trillion. Over the most recent 12-month period ended January 31, 2019, the BOJ added only ¥30.2 trillion to its balance sheet, the smallest such gain since March 2013:

In percentage terms, the BOJ increased its balance sheet by 5.7% over the 12-month period ended January 31, the smallest percentage increase since May 2012, before QQE had even begun.

The BOJ has been buying mostly Japanese government securities (JGBs and short-term bills). But it also buys some equity ETFs, Japanese REITs, and corporate bonds. Japanese government securities are the largest asset class on the balance sheet. The amount of these securities rose in January by ¥3.9 trillion from the prior month, to ¥471.5 trillion.

This amounts to nearly 50% of all outstanding Japanese government debt – up from about 14% in late 2012.

For the 12-month period ended January 31, the BOJ added “only” ¥25.4 trillion of JGBs and bills, a far cry from its assertions that it would add ¥80 trillion a year. It has not added ¥80 trillion of government debt since the 12-month period ended April 2017.

Clearly, the “QQE Taper” is well underway, despite whatever the BOJ may proclaim to keep everyone guessing.

The Fed has already reduced its balance sheet by over $400 billion since the start of its QE unwind in October 2017 and for now continues to run its QE unwind on automatic pilot.

The ECB tapered its massive QE to zero as of December 2018 and is currently only planning to replace securities when they mature to keep its balance sheet roughly level.

And in 2019, markets are facing a situation for the first time in a decade where the big three QE’ers – the Fed, the BOJ, and the ECB – will on net whittle down ever so slowly the assets on their combined balance sheets, with the BOJ continuing to add a smidgen, with the ECB maintaining what it has, and with the Fed continuing its roll-off.