Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, http://www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

A vicious cycle, kicked off by cheap debt that’s suddenly not cheap, after 8 years of experimental monetary policies.

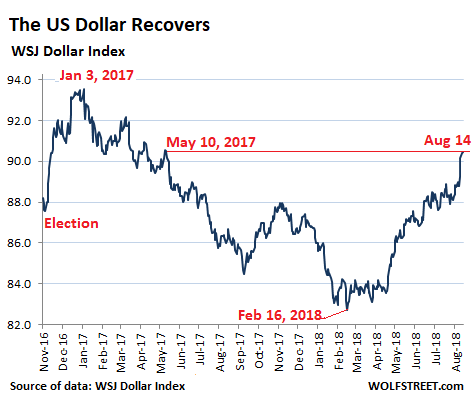

The dollar has risen nearly 2% since Thursday last week. Since April 17, when this move started, the dollar has surged over 8%, based on the WSJ Dollar Index, which tracks the dollar against the currencies of 16 key trading partners, including Mexico and China. From its low on February 16, the dollar has now risen 9.3% to the highest level since May 10, 2017:

The narrower Dollar Index (DXY), which tracks the dollar against six other currencies but not the Mexican peso and the renminbi, rose to 96.73, the highest since June 2017.

Not included in the two dollar indices are the Turkish lira and the Argentine peso, both of which have collapsed, with the lira down 43% and the peso down 33% against the dollar since April.

That recent surge in the dollar makes dollar-denominated debt across the emerging economies harder to service. After the collapse of the Turkish lira and the Argentine peso, this is particularly the case for dollar-debt and other foreign-currency debt in those countries.

Over $200 billion of USD-denominated bonds and loans, issued by emerging market governments and companies will come due during the remainder of 2018, according to the Wall Street Journal. About $500 billion will come due in 2019. They will need to be paid off or refinanced.

When financial conditions in the emerging markets get tight, some economies will find it difficult to pay off or refinance that debt because dollar investors are going to be leery and would want to be compensated for large risks – a consideration that was absent as little as a year ago, when Argentina was able to sell 100-year dollar-bonds. As far as these bondholders and creditors are concerned, it will take either an IMF-bailout to make them whole, or a default. Argentina has already made a deal with the IMF to bail out its bondholders.

Through 2025, emerging market governments and companies face $2.7 trillion in USD-denominated bonds and loans that will come due and have to be paid off or refinanced. This does not include euro and yen-denominated debt, of which these countries also have a pile.

For example, in April this year, the Mexican government was able to sell ¥135 billion ($1.26 billion) in “samurai bonds” with maturities of five, seven, 10 and 20 years, at what the Ministry of Finance termed “a historically low cost.”

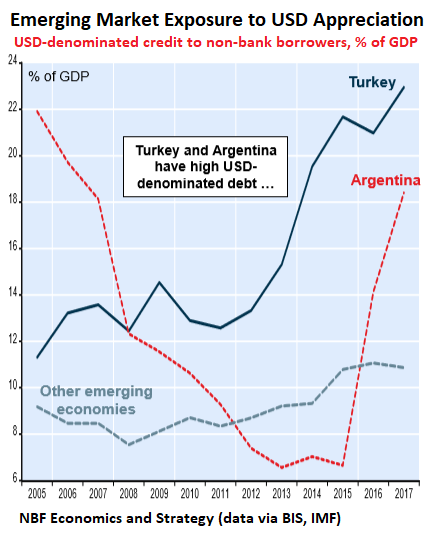

In terms of the USD-denominated debt as percent of GDP – not including other foreign currency debt – Turkey is on the forefront, followed by Argentina, according to a report by Krishen Rangasamy, Senior Economist at Economics and Strategy at NBF. These two countries have gotten hit not only by the USD-appreciation but more importantly by the separate collapse of their own currencies. Citing data by the Bank for International Settlements, he writes that in Turkey, USD-denominated debt by non-bank borrowers “hit a record $195 billion at the end of 2017, or a stunning 23% of GDP.”

Turkey also has a heavy load of euro-denominated debt, and its total foreign-currency debt now amounts to over 50% of GDP.

Total foreign-currency denominated debt also amounts to over 50% of GDP in Argentina, Hungary, Poland, and Chile, according to the Wall Street Journal, citing Deutsche Bank.

A country like Turkey can destroy its own currency and thus diminish the burden of its local-currency debt. But it cannot do this with foreign-currency debt. Instead the reverse is true: Foreign-currency debt becomes more burdensome. And this creates a vicious cycle; as this debt becomes more difficult to service, the default risk rises, and foreign currency investors are then even more inclined to stay away, leading to more capital outflows, and making it nearly impossible to refinance and service that debt – thus speeding up the trip to a default.

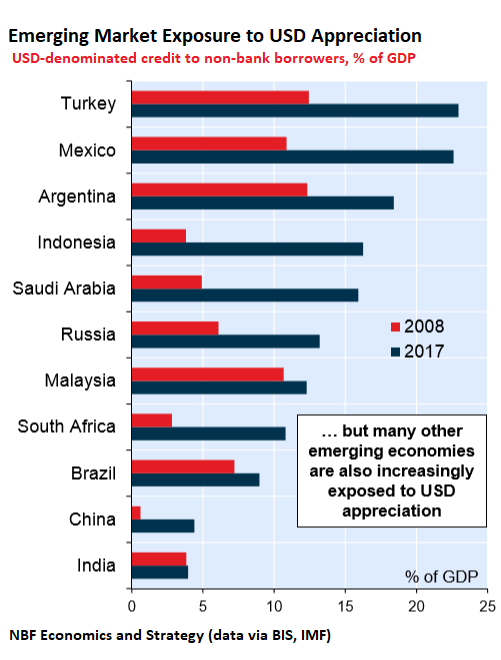

The chart below shows the increase in USD-denominated debt for the top emerging market economies from 2008 (red) to 2017 (blue) as a percent of GDP. Note how that USD-denominated debt has surged as a percent of GDP since 2008:

Mexico is right up there, and it’s vulnerable, but compared to Turkey and Argentina, it has better current-account balances and higher foreign exchange reserves. And Indonesia has seriously arrived on the risk scene over the past few years.

This period between 2008 and 2017, during which this surge in foreign-currency debt occurred in the emerging markets, happens to be the era of experimental monetary policies in the US, Europe, and Japan that entailed an enormous amount of money-printing to artificially repress interest rates – in other words, cheap debt. These experimental monetary policies had the express purpose of encouraging a debt-fueled binge of consumption and investment. That is now in the past, and what remains is the hangover – the debt that these countries cannot control or inflate away.