Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

The Fed will keep tightening until these junk bonds buckle.

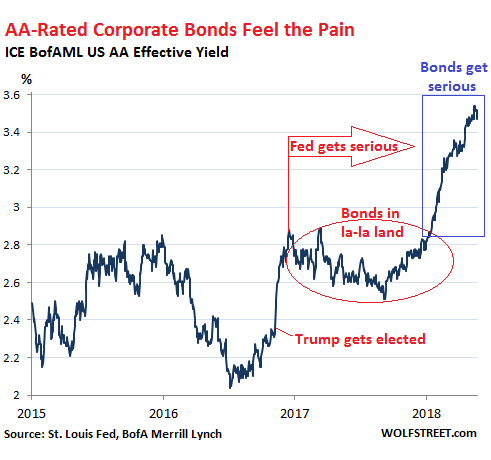

High-grade corporate bonds have had a hard time. Yields have surged as prices have fallen. The S&P bond index for AA-rated corporate bonds is down 3.2% so far this year. Losses are concentrated on bonds with maturities of 15 years and over. They’re down 7%, according to Bloomberg. As prices have declined, yields have surged, with the average AA yield now at 3.47%, up from around 2.2% in mid to late-2016:

In the chart above of the ICE BofAML US AA Effective Yield Index, I marked some key events, in terms of the bond yield:

- The election in November 2016, after which the yield spiked.

- In December 2016, the Fed’s second rate hike in this cycle. This was when the Fed got serious and added an increasingly more hawkish – or less dovish – tone. But the market blew it off, yield fell again, and bonds returned to la-la-land.

- In September 2017, the Fed announced details of its QE unwind, and yields began to rise again and then started spiking in late-2017. This was when the bond market got serious.

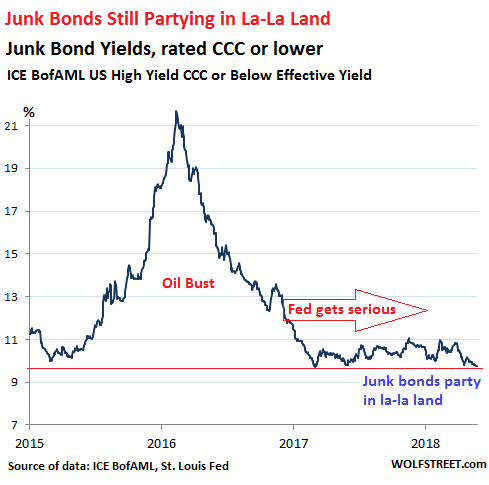

But at the riskiest end of the spectrum, with corporate bonds rated CCC or below (deep into junk), there is no such pain. In fact, the S&P bond index for CCC rated bonds is up 4.3% so far this year. They’ve had a blistering 82%-run since February 2016, when Wall Street decided that the oil bust was over and plowed new money into junk-rated energy companies.

The average yield of bonds rated CCC or lower is now at 9.78%, down from 12.5% in December 2016, when the Fed got serious, and down from 22% during the peak of the oil bust:

Before we get to one of the causes of this divergence between suffering high-grade corporate bonds and low-grade junk bonds partying blissfully in la-la land, here is another piece of the puzzle.

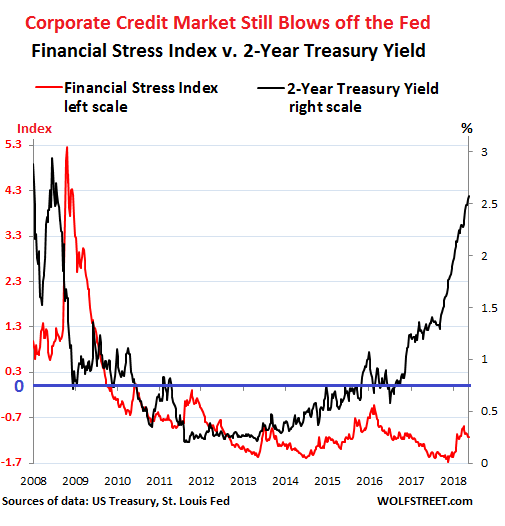

The US Treasury two-year yield has surged since late 2016 and closed today at 2.53%. This end of the market is responding to the Fed’s tightening cycle. By raising rates and unwinding QE, the Fed wants to tighten financial conditions. In other words, it wants to make it a harder and more expensive to raise funds, and it wants investors to become more risk averse. This is the mechanism by which it transmits its monetary policy to the markets. But financial conditions haven’t tightened yet.

These “financial conditions” show up in the FOMC minutes. In yesterday’s release, they showed up a dozen times: in summary, financial conditions tightened “a little” but remain “accommodative,” and this accommodation is what the Fed wants to remove.

This is reflected in the St. Louis Fed Financial Stress Index, released today for the week ended May 15. It is designed to track financial conditions that companies face in the markets. It reached record lows last November, with extraordinarily little “financial stress” in the markets after years of ultra-easy monetary policies. Not exactly the moment that sends investors scrambling to top off their precious metals storage. The index has since zigzagged higher but remains way below historical “normal.”

The chart below shows the Financial Stress Index (red line, left scale) and the two-year yield (black line, right scale). The index has a value of zero under “normal” financial conditions (blue horizontal line). When financial conditions are tighter than normal, the index has a positive value. When conditions are easier than normal, the index has a negative value:

In the past, the two-year yield led, and the Financial Stress Index followed with a lag of half a year to a year. As the above chart shows, the lag is now wrapping up its second year. But eventually, financial stress will rise to catch up with the surging two-year yield. That’s when financial conditions get tighter and junk bonds get driven out of la-la land.

There are a number of reasons behind this divergence between the pain of high-grade corporate bonds, and the bliss of CCC-rated junk bonds. One reason – a powerful one – is the new tax law.

The new tax law encourages corporations with “overseas cash” to “repatriate” it under advantageous tax rules. But this “overseas cash” is neither overseas nor cash. It has been invested in all kinds of US securities, particularly Treasuries, often short-term Treasury bills to provide liquidity when needed, and high-grade corporate bonds.

Now companies are repatriating this “cash” to buy their own shares. Share buybacks surged in the first quarter to more than $180 billion. To fund these share buybacks, companies are selling their bond holdings. This is a zero-sum game. Share buybacks in this quantity seriously prop up the stock market, but at the same time, they pull the rug out from under the bond market.

Apple has promised a $100 billion share buyback program, the largest in world history. It has already embarked on it, and the once voluminous buyer of bonds has become a net seller. Other big companies have also piled into the game of selling their bond holdings to raise the cash to buy back their own shares. There is not a lot of liquidity in the corporate bond market. So this selling has an impact, which explains part of the pain in the high-grade bond market.

And junk bonds? Companies don’t want to risk their “cash and cash equivalent” on risky financial investments. They tend to be conservative. Their risk-taking is focused on operational risks, such as developing new products that might flop or building new plants that might not be needed. So they don’t invest in risky securities, such as CCC-rated bonds. But now that they’re selling their holdings, there are no CCC-rated bonds to sell, and they can’t put pressure on the low end of the junk bond market from that direction. And that’s one of the reasons low-end junk bonds are still waiting to be driven from la-la land.