Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, http://www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

Wages rose with inflation, but not nearly enough to pay for “quality improvements,” which is why working people feel increasingly impoverished.

There are two ways to answer the thorny question: One way, as measured by the official CPI for new vehicles. And the other way, as measured by retail prices. So here are the retail prices, as measured by base MSRP, for one of the bestselling four-door sedans in the US, the Toyota Camry LE, going back to 1990. And in a moment, we’re going to compare this to the official CPI for new vehicles.

The base MSRP for the Camry LE jumped nearly 70% in 30 Years.

You already knew this: New vehicles have gotten a lot more expensive over the years, regardless of what CPI says. In 1990, the base Camry LE with a four-cylinder engine and automatic transmission came with an MSRP of $14,658. The just-arriving 2020 base Camry LE with a four-cylinder engine and automatic transmission comes with an MSRP of $24,840, up 69.5% from 1990:

The $1,080 jump (+4.7%) in price from the 2017 model year to the 2018 model year was the result of a redesign of the 2018 Camry that included appearance, dimensions (longer, lower, wider), aerodynamics (the sculpted face), and performance (the 2.5 liter 4-cylinder engine was boosted to 203 horsepower and 186 lb-ft of torque).

The purpose of a redesign is multi-fold: To catch up with or leapfrog the competition; to improve sales or keep them from collapsing further; and most importantly, to be able to charge a higher price. The latter doesn’t always work because competition is fierce, but it certainly happened in 2018.

Why use MSRP?

We all know that no one pays MSRP. Automaker heap on rebates and incentives, and dealers give discounts. But this was also the case in 1990. So that’s a constant.

MSRP and dealer “invoice” are set by the automaker at the beginning of the model year and don’t change for the model year. What changes are the incentives, rebates, and discounts, depending on market conditions. If dealers drown in inventory, and sales get bogged down, discounts and incentives are increased to move the iron. This can change from one day to the next. But MSRP is fixed for the model year. Nothing is perfect, but using MSRP allows us to approximate price changes.

We also know that once we add an option to the base LE trim package, the MSRP jumps. For example, in 2020, the “starting at” MSRP is $24,840. But the most common models listed on dealer inventories are priced higher because they have more equipment. But that was the case in 1990 as well. Apples to apples, as close as possible: We compare base MSRP of the LE over the years.

How did I get this data?

Erik Senko, a former hedge fund manager and now Adjunct Professor at the Business Dept. of Santa Monica College who teaches investment and personal finance, sent me some amazing new-vehicle pricing data going back decades from a research project that one of his students, Jisoo Kim, submitted. The goal of her project was different from my goal: it was focused on the three top-selling four-door sedans in each model year and included models from GM, Ford, Honda, Nissan, and other brands.

My goal is to show price changes over the years, within the same model, regardless of best-seller status. I focus on the Camry LE because her data set was the most complete over the years for this model, and I only needed to dig up the data for a few years that were missing in her data set when the Camry wasn’t in the top three. I contacted Jisoo Kim to confirm how she’d obtained the data – she’d used various sources available on the internet. This was a lot of digging. Kudos to her.

Price increases are small until suddenly they aren’t.

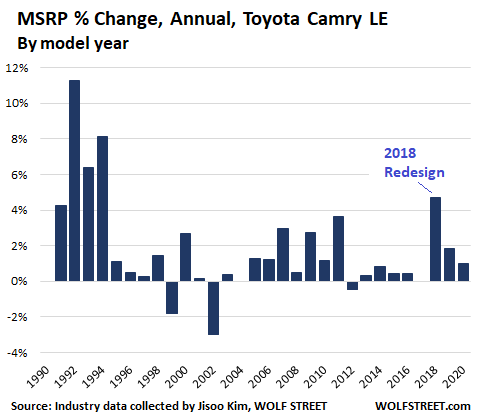

The chart below shows the year-over-year percent change in the base MSRP of the Camry LE by model year. Note the 4.8% jump in 2018, following the redesign. The years before the redesign, prices were nearly flat. The chart also shows that price increases can be carried too far, causing resistance in the market, whereupon the automaker decides to adjust the MSRP the following year.

Oh no, not CPI!

Another way of looking at new-vehicle price increases over the years – this tends to cause a lot of hollering for good reason – is the official Consumer Price Index for new vehicles, released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which uses “hedonic quality adjustments.” The CPI does not attempt to show how costs of living rise. It attempts to show how the price of the same thing or service changes over time, to measure the loss of purchasing power of the dollar.

The Camry LE came with a five speed automatic transmission in 1990 and today it comes with an electronically regulated, silky-smooth, shiftable, eight-speed automatic transmission. This is an “improvement” of the product, and the costs of this improvement are removed from the CPI in increments as these costs develop over the years – from five-speed to six-speed to seven-speed to eight-speed – the “hedonic quality adjustments.”

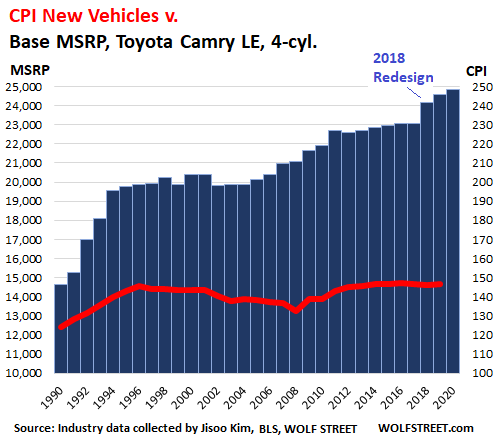

Which leads to the discrepancy: The base MSRP of a Camry LE today has soared by nearly 70% since 1990, while the CPI for new vehicles has risen only 22% over the same period, and has been flat since 1997.

The chart below shows the MSRP by model year for the Camry LE (blue bars, left scale) and the CPI for new vehicles (red line, right scale). To show the relative changes in a comparable manner, I put them on the same scale, with only a difference in decimals: the MSRP scale runs from 10,000 to 25,000 and the CPI-new-vehicles scale runs from 100 to 250:

If you buy a Camry today, you’re likely to pay around 70% more than in 1990, but according to this data, the dollar with regards to new vehicles has lost only 20% of its value over the time, and the rest of the price increases are attributable to quality improvements.

It could very well be that the costs of the quality improvements have been over-estimated, and as these over-estimated costs are then removed from CPI, it would understate CPI.

But the quality improvements have been enormous over the three decades. Many of the features were unheard-of in 1990 and are now standard across the industry. Since I used the example of the Camry LE, I’ll stick with it.

The Camry LE went from two airbags in 1990 to 10 airbags today. Other safety features include tire-pressure monitoring system, front and rear crumple zones, side-impact bars, energy-absorbing collapsible steering column, stability control system that coordinates antilock brakes and traction control systems to keep the car from flipping, spinning out, and doing other crazy things. Stability control systems were unheard of in 1990, when basic antilock brakes were all the rage.

Power has improved. There is distance pacing cruise control, and myriad other things, many of them unheard-of in 1990, but now nearly standard, including an exterior parking camera at the back of the car that turns on automatically when you put the vehicle in reverse and shows on a screen in the dashboard that you’re about to run over your cat sleeping right behind the car.

As these systems are added to the vehicle over time, their incremental costs are removed from CPI since CPI attempts to measure what the “same thing costs over time.”

However, this leaves the economy – and people – with a problem: While wages have grown in nominal terms, “real” wages adjusted for CPI have been flat for men since the 1970s, and have grown only for women, but from a much lower base. In terms of our time frame here since 1990, “real” household incomes have only grown 22% since 1990, but the cost of a Camry LE has soared 70%.

This is the difference between “inflation” and “cost of living.” Things get better but they get more expensive. But the problem in the logic is that you cannot buy a new 1990 Camry anymore, even if you don’t want all the improvements, and you just want a cheaper car. In other words, wages rose with inflation, but the increase was not sufficient to pay for the quality improvements of everything around us, which makes a big part of the population feel increasingly impoverished.