via nakedcapitalism:

I find it hard to get excited about stock market risks unless defaults on the borrowings can damage the banking/payments system, as they did in the Great Crash. This is one reason the China perma-bears have a point: even though the Chinese government has managed to do enough in the way of rescues and warnings to keep its large shadow banking system from going “boom,” the Chinese stock markets permit much higher level of borrowings than those in the West, which could make them the detonator for knock-on defaults.

The US dot-com bubble featured a high level of margin borrowing, but because the US adopted rules so that margin accounts that get underwater are closed and liquidated pronto, limiting damage to the broker-dealer, a stock market panic in the US should not have the potential to produce a credit crisis.

But if stock market bubble has been big enough, a stock market meltdown can hit the real economy, as we saw in the early 2000s recession. Recall that Greenspan, who saw the stock market as part of the Fed’s mission, dropped interest rates and kept them low for a then unprecedented nine quarters, breaking the central bank’s historical pattern of reducing rates only briefly.

Greenspan, as did the Bank of Japan in the late 1980s, believed that the robust stock market prices produced a wealth effect and stimulated consumer spending. It isn’t hard to see that even if this were true, it’s a very inefficient way to try to spur growth, since the affluent don’t have anything approach the marginal propensity to spend of poor and middle class households. Subsequent research has confirmed that the wealth effect of higher equity prices is modest; home prices have a stronger wealth effect.

A second reason for seeing stock prices as potentially significant right now be is that the rally since Trump won the election is important to many of his voters. I have yet to see any polls probe this issue in particular, but in some focus groups, when Trump supporters are asked why they are back him, some give rise in their portfolios as the first reason for approving of him. They see him as having directly improved their net worth.1

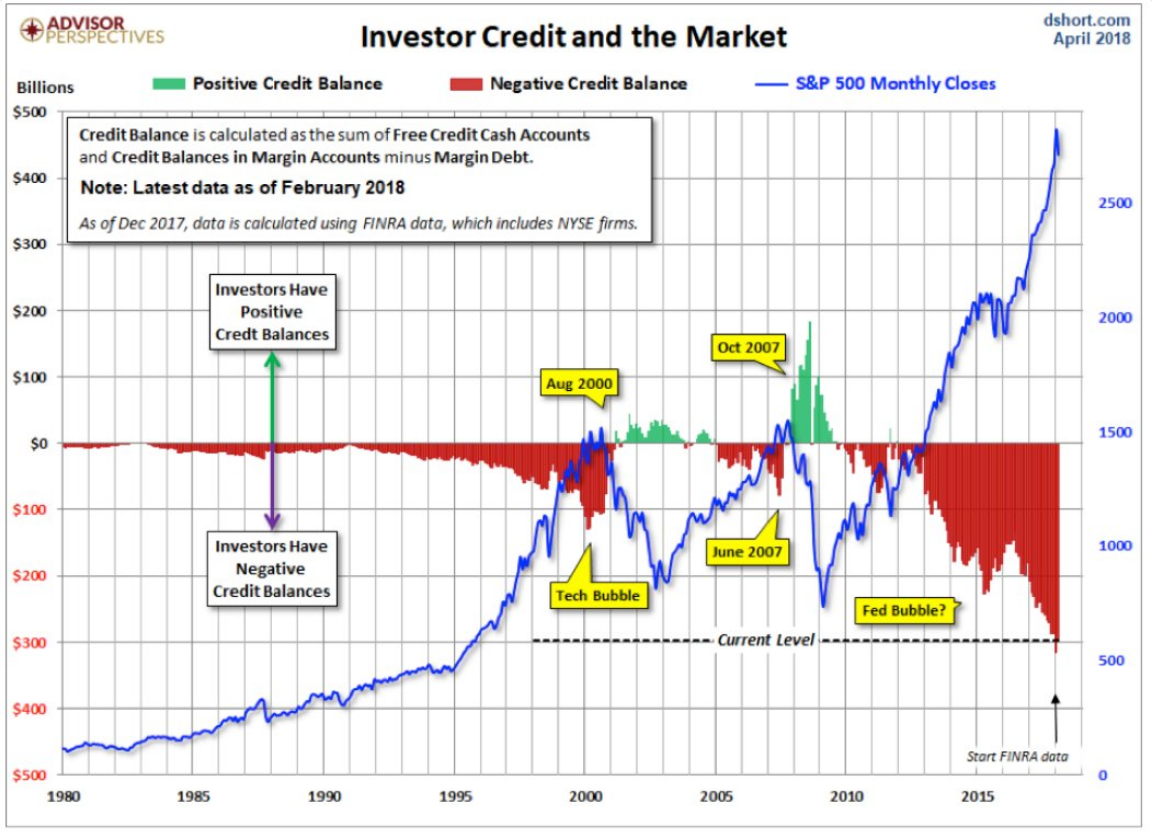

With that long-winded introduction, this chart, from Brad Lamensdorf, a portfolio manager at Ranger Alternative Management, via Business Insider, in many ways speaks for itself:

One implication is obvious: highly levered equity markets are subject to more violent downdrafts as margin calls lead to forced sales.

But Lamensdorf makes a second point: the 1% (and I would assume not the 0.1%) are borrowing against stocks: “Among those with the most at stake are the top one percenters, who’ve borrowed to buy stocks and used their portfolios as collateral for other lines of credit…”

The propensity to borrow is a big difference between the affluent classes of yore and their modern-day counterparts. A colleague, after making a nine-figure fortune in real estate, went on to establish what became one of two largest lenders against art. The idea that a rich person would have personal property in hock would have been unthinkable in say, the 1960s. The widespread financialization of the economy has completely destigmatized the use of credit….as long as you don’t get into the crosshairs of debt collectors….as did Annie Liebowitz, who had pledged her entire photography portfolio plus several houses as collateral for a loan from Art Capital. She allegedly refused to sell her back catalogue as promised to retire the borrowings. Art Capital sued, threatening to put her into bankruptcy and seize the pledged assets. A new lender came in, paying off Art Capital, in return for becoming Liebowitz’s sole creditor (as in presumably getting the rights to the collateral) and as I read Liebowitz’s comment to the Guardian, for an interest in her new work.2