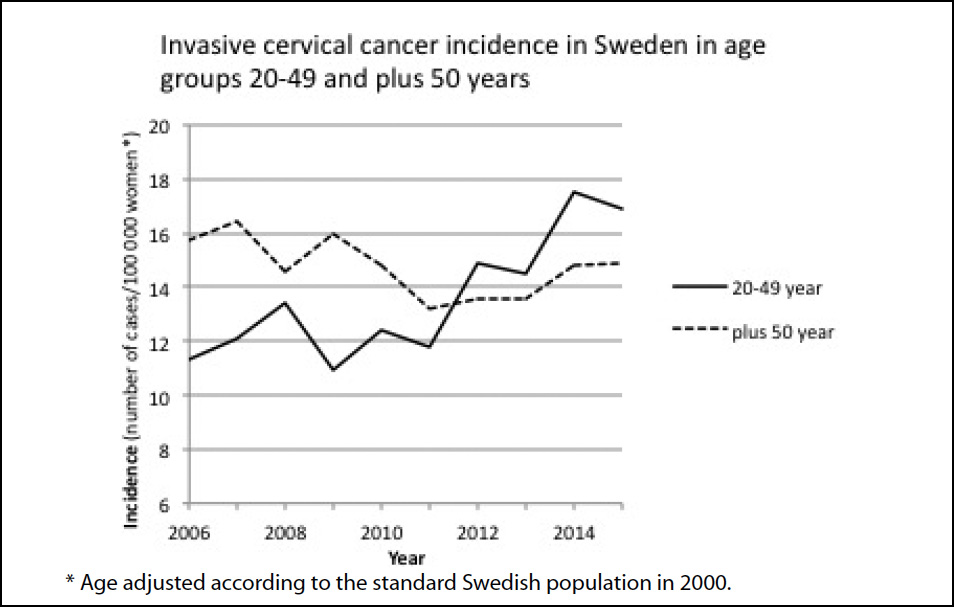

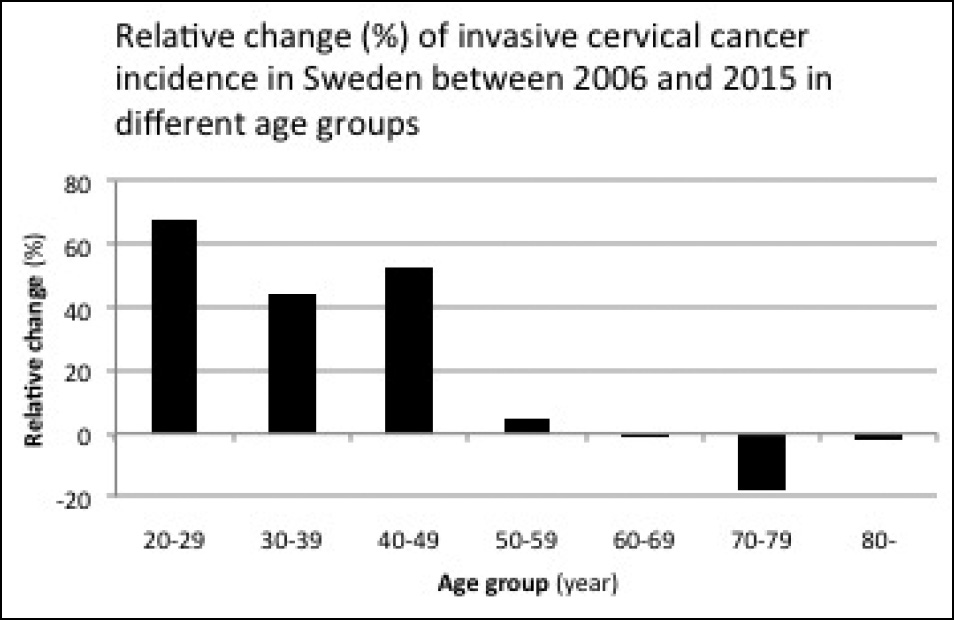

A new study published in the Indian Journal of Medical Ethics examined cervical cancer rates among women in Sweden and discovered a link between increased cervical cancer rates among women aged 20-49 during a two-year period between 2014 and 2015, corresponding to increased HPV vaccination rates in this population group, years earlier, when mass HPV vaccinations started in Sweden.

Women above the age of 50, during this two-year period, saw no significant cervical cancer increase and were likely too old to have been vaccinated with the HPV vaccine.

Since the study casts doubt on the efficacy of the HPV vaccine, and, in fact, links the vaccine to increased cancer rates, it is highly unlikely you will read about this in the U.S. corporate-sponsored media, where nothing negative about the blockbuster HPV Gardasil vaccine is allowed.

via ijme.in:

Discussion

I discuss below some possible explanations for the increase in the incidence of cervical cancer among young women in Sweden.

A change in the routine or other technical or methodological changes during the study period may affect the reported incidence of cervical cancer due to changes in the sensitivity of the diagnostic tools. The reported change in the incidence among younger women and the fact that the increase was noted in most counties in Sweden argue against this explanation. Neither was such an explanation given by the NKCx in its annual report of 2017, with data up to 2016 (1). Recently, when the Swedish media discussed the increase in the incidence of cervical cancer, the health authorities were unable to explain the increase.

Another possibility is that HPV vaccination could play a role in the increase in the incidence of cervical cancer. About 25% of cervical cancers have a rapid onset of about 3 years including progression from normal cells to cancer (3, 4). Therefore, an increase may be seen within a short period of time. Gardasil was approved in Sweden in 2006. In 2010, the vaccination of a substantial number of girls started. In 2010, about 80% of the 12-year-old girls were vaccinated. Combined with 59% of the 13–18-year-old girls vaccinated through the catch-up programme in the same period, one can say that most girls were vaccinated. Thus, the oldest girls in the programme were 23 years old in 2015; and this is well within the younger age group shown in Fig. 1. For the older age group represented in Fig. 1, data on exposure to vaccinations is not available. In 2012–2013, most young girls were vaccinated.

The vaccine does not need to initiate the cancer process. There is a possibility of the vaccine acting as a facilitator in an ongoing cancer process. I discuss below some possible mechanisms of how the vaccine might influence the incidence of cervical cancer.

The efficacy of HPV-vaccines has been evaluated by studying premalignant cell changes in the cervix called CIN2/3 and cervical adenocarcinoma in situ or worse (5). The efficacy was calculated for individuals who have not been exposed to HPV 16 and 18. These individuals are called naïve. The vaccine is efficacious only in individuals not previously exposed to HPV 16 and 18 (naïve individuals). If an individual has already been exposed to HPV 16 and 18, no new antibodies are made. Therefore, the vaccine will not work for non-naïve individuals. HPV 16 and 18 are responsible for about 70% of all cervical cancers (5). It is therefore crucial to give the vaccine to naïve individuals. During their review of Gardasil by the FDA, the efficacy of the vaccine was also evaluated on individuals who were exposed to the oncogenic HPV strains before vaccination since individuals who are non-naïve will also receive the vaccination. A concern was raised for disease enhancement (increase in CIN 2/3, cervical adenocarcinoma in situ or worse) in this subgroup (5). In these individuals, the efficacy was -25.8% (95% CI: -76.4, 10.1%) (5). Thus, vaccination with Gardasil of non-naïve individuals who had HPV 16/18 oncogenes before vaccination showed a higher level of premalignant cell changes than did placebo. The FDA statisticians could not draw any firm conclusions. In their analysis, the FDA included only cases with HPV 16/18. If cases with oncogenes other than HPV 16/18 had been included in the analysis, the efficacy of data could have been even more unfavourable.

The increase in premalignant cell changes in non-naïve individuals, as suggested by the FDA, is consistent with the knowledge that vaccination can cause reactivation of both target and non-target viruses (6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12). For Gardasil, the HPV types 16 and 18 are called target HPVs since the vaccine contains antigens for these two HPV types. Other HPV types for which the vaccine does not contain any antigens are called non-target HPVs. For individuals exposed to Gardasil, evidence of a selective and significant reactivation of the oncogenic non-target HPV types 52 and 56 was reported in the genital tract for all women (13). This article studied women 13–22 and 23–40 years of age from 2008 to 2013. The target HPVs 16 and 18 decreased only in the younger age group but oncogenic non-target HPVs increased in both the groups, 20%–40% and 8%–30%, respectively. The increase in the total burden of non-target oncogenic HPVs for vaccinated individuals may be consistent with the findings in the FDA report where the efficacy of the HPV vaccine was less favourable for non-naïve women compared with those on placebo. A possible mechanism to explain the increased incidence of cervical cancer may therefore be virus reactivation as described above.

In the evaluation of Gardasil by the FDA, it was found that about 25% of all individuals were non-naïve in the pivotal trial (5). There are more than 200 types of HPVs, of which 12 are currently classified as high-risk cancer types (14). HPV may be found in non-sexually active girls (15). It may be transmitted through non-sexual means, either by way of mother to child, from contact with infected items, from self-inoculation or hospital-acquired infection (16), or via blood (17, 18). The virus can lie latent in any tissue and escape detection by standard techniques (19). It can also be redistributed systemically during the lytic cycle into previous virus-free tissues (auto-inoculation), for example infecting an earlier virus-free cervix.

Recently, it was shown that previously HPV-positive women with normal cytology remained at increased risk of pre-neoplasia (CIN3) despite two follow-up HPV-negative tests (20). “Proving that HPV is absolutely gone is, of course, impossible,” state Brown and Weaver in an editorial in 2013 (21). Therefore, non-naïve-individuals can be seen among females at all ages. Sometimes these individuals have measurable HPV and sometimes not. When taking these results into account, the proportion of non-naïve individuals may be underestimated in the studies.

Since the vaccine is recommended for up to 45 years in the European Economic Area, it is possible that the vaccination has facilitated the development of new or existing cervical cancer among women who were non-naïve at the time of vaccination. Vaccination against HPV has started in Sweden during the study period. Gardasil, the vaccine mostly used in Sweden, was approved in September 2006. There are no statistics for the overall use of Gardasil in Sweden. For young girls (12–13 years of age) there are special programmes for vaccination. About 75%–80% of all girls are vaccinated in this age group (22). For older girls there are catch-up programmes. For older girls/women who will be vaccinated on-demand, data on frequency of vaccination are missing. The increase in the incidence of cervical cancer between 2006 and 2015 was 50% (corresponding to 115 absolute cases). Therefore, the vaccination coverage of the Swedish population does not need to be very high to explain a role for the vaccine. The findings could be consistent with on-demand vaccination of women above 18. In Sweden there were 702,946 cervical cell screenings performed on women aged 23–60 years in 2016 (1).

Could the HPV vaccination cause an increase in invasive cervical cancer instead of preventing it among already infected females and thereby explain the increase in the incidence of cancer reported by the NKCx in Sweden? The increased incidence among young females, the possibility of virus reactivation after vaccination, the increase in premalignant cell changes shown by the FDA for women who were already exposed to oncogenic HPV types and the time relationship between the start of vaccination and the increase in cervical cancer in Sweden could support this view. The answer to this question is vital for correctly estimating the benefit-risk of this vaccine. More studies focused on already HPV-infected individuals are needed to solve this question.

h/t SuperCharged2000