Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, http://www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

Supply chains begin to shift back to US suppliers, “due to tariffs.”

Two US manufacturing reports were released this morning, one showing the fastest decline since June 2009, and the other showing an increase in growth, and given the bad numbers recently, the fastest growth in five months. So get ready for mild whiplash.

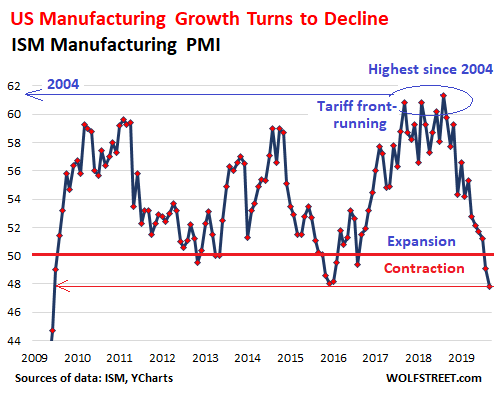

The bad news came from the Institute of Supply Management (ISM), whose Manufacturing Report on Business for September fell to 47.8. In this diffusion-type index, a value above 50 means growth and a value below 50 means decline. Today’s reading was the second month in a row in decline mode (below 50), and the fastest decline since June 2009.

This decline followed a huge surge peaking in 2018 with the fastest expansion since 2004. This surge was the result of efforts by US and foreign industries in 2017 and 2018 to front-run any tariffs. They over-ordered and over-produced and over-stuffed their warehouses with inventory, and those excesses are now being wrung out of the system (data via YCharts):

These types of indices are based on how a panel of executives of manufacturing companies – names are not disclosed – see their own businesses. In terms of the ISM Manufacturing report:

Demand contracted, driven by export orders: New orders translate into future production, and so this is not indicating a bottom just yet:

- New Orders contracted in September (47.3) at about the same rate as in August (47.2), dragged down by New Export Orders.

- New Export Orders plunged in September (41.0), after a sharp contraction in August (43.3)

Production contracted faster in September (47.3) than in August (49.5).

Backlog of Orders fell faster in September (45.1) than in August (46.3), as production is now clearing the backlog.

Employment contracted faster in September (46.3) than in August (47.4).

Supplier Deliveries expanded in September (51.1) more slowly than in August (51.4)

Inventories contracted in September (46.9), as companies were trying to whittle them down, from the inflated levels after the front-run efforts in 2017 and 2018. Customers’ Inventories also contracted in September (45.5), from previously elevated levels to “about right,” as the report said.

Prices declined a tiny bit in September, near the flat line (49.7) compared to the steeper decline in August (46.0).

The report summarizes: “Global trade remains the most significant issue, as demonstrated by the contraction in new export orders that began in July 2019. Overall, sentiment this month remains cautious regarding near-term growth.”

Of the 18 manufacturing industries, 15 reported declines and only three reported growth: Miscellaneous Manufacturing; Food, Beverage & Tobacco Products; and Chemical Products.

The comments that panelists provided, reflected “a continuing decrease in business confidence.”

A second opinion.

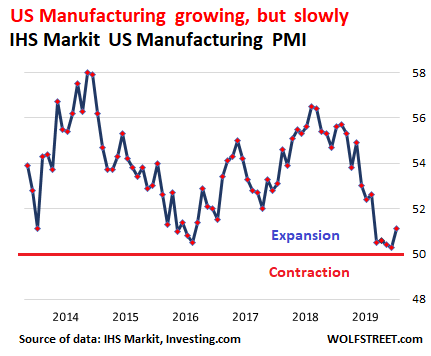

The IHS Markit U.S. Manufacturing PMI, also released this morning, was in expansion mode for September (51.1), after four months of being near-flat:

“September PMI data indicated a marginally faster rate of improvement in the health of US manufacturing, though the overall picture remained one of a struggling goods-producing sector that has suffered its worst quarter since 2009,” the report said.

This expansion of the headline PMI was largely driven by the upturn in production – while modest, it was the fastest since April, based on “slightly stronger client demand and efforts to clear backlogs.”

New orders expanded, driven by an increase in domestic client demand, but weighted down by export orders that fell the second-fastest in nearly five years.

Employment expanded “marginally,” as firms were encouraged by rising new orders and production.

Input prices rose due to the “impact of tariffs,” but wait, “a drop in demand for inputs kept cost rises relatively muted.”

Output prices also rose “modestly,” as firms “sought to pass on higher costs, while maintaining efforts to be competitive.”

In terms of their output expectations for the next 12 months, “firms expressed a greater degree of confidence”; and “the level of optimism” reaching “a three-month high but remained relatively subdued overall.”

Shifting production back to the US:

The report included a fascinating observation on how some supply chains were shifting back to the US to avoid the tariffs, but this isn’t easy to do quickly, and so “supplier performance deteriorated further as firms increasingly reported a change to domestic suppliers, due to tariffs, with vendors struggling to deliver goods to manufacturers amid capacity issues.”

Despite the improvement in the PMI for September, the very weak July and August readings produced the weakest quarterly reading since 2009. The report added:

“It’s also far from clear that the trend will improve in the fourth quarter. Inflows of new work remain worryingly subdued, to the extent that current production growth is having to be supported by firms increasingly eating into order book backlogs.”

And reminiscing about the happy times of front-running the tariffs: “The current situation contrasts markedly with earlier in the year, when companies were struggling to keep up with demand. Now, spare capacity appears to be developing, which is causing firms to curb their hiring compared to earlier in 2019 and become more cautious about costs and spending.”

In summary, Manufacturing is either in a mild recession and perhaps coming out of it, or sinking deeper into a not-so-mild recession, depending who does the counting.

How important is manufacturing to the US economy?

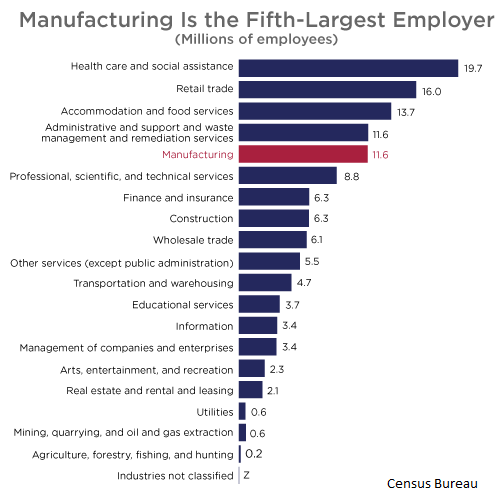

In terms of employment, manufacturing is the fifth-largest sector with 11.6 million workers. And it pays well, with an average annual payroll of $57,266 per employee, according to the Census Bureau today:

These manufacturing jobs are not what they used to be, as automation and the challenges it brings have taken over. “These workers are not only highly skilled, but extremely well-educated,” the Census Bureau says. Based on its 2016 Current Population Survey, nearly 30% of manufacturing employees age 26 or older had a bachelor degree or higher.

So manufacturing is important. A decline in manufacturing puts a damper on the US economy. And relying more on suppliers in the US — the first signs are now being reported — would boost the economy.

But services dominate the US economy. In the US, the biggest service sectors in terms of dollars are finance, insurance, and health care. According to the World Bank, services account for 77.4% of the US economy as measured by GDP, behind only Macau, Hong Kong, and Luxembourg. In Japan, services account for 69.1% of GDP, in Germany 61.5%; and in China 52.2%.

In the US, services provide 79.1% of the employment. In Japan, 72.1%, in Germany 71.6%, in China 44.6%.

In other words, the manufacturing recession that has spread around the world is impacting other economies far more than the US economy. It might pull Germany into an overall recession even if services hang in there. But in the financialized US economy, services would have to slow, meaning finance, insurance, and healthcare, which dominate services, would have to slow. But so far – industry insiders are being heard knocking on wood – this hasn’t happened yet.

Services are Hopping. And the #1 Biggie is Hopping the Fastest. Read… The Financialization of the US Economy