via Kyler Hasson

- Some portion of tax cuts will be passed along to consumers.

- Prior evidence shows that companies don’t see big benefits from tax cuts, on aggregate.

- High valuations mean low prospective returns for equity investors going forward.

- Tax cuts could lead to higher interest rates, which would hurt equity valuations.

- With similar earnings and higher interest rates, tax cuts counterintuitively hurt long-term equity returns.

US stocks have performed exceptionally well since the market bottomed in early 2009, returning ~350%. This rally has continued over the past year even as stocks have looked increasingly expensive to many investors. Part of the recent gains can certainly be attributed to the recent tax bill that has sent corporate tax rates to 21% from the previous rate of 35%.

If stocks go up in anticipation of tax reform, investors are implicitly expecting that tax cuts will flow through into businesses’ income. It is important for investors to understand just how much of the tax cuts will be captured by businesses and how much will be captured by consumers in the form of lower prices. It seems that most investors are assuming that businesses (or at least the businesses they own) will capture all of the decreases in taxes in the form of higher after-tax profits. However, Econ 101 tells us that the benefit will be shared among businesses and consumers, depending on how competitive the industry is.

Let’s take a look at two industries to see how lower corporate taxes might either flow through to consumers or to the businesses.

First, think about the trucking industry. Trucking is intensively price-competitive – freight brokers call up different trucking companies and give the business to whoever offers to do it at the lowest price, and there are often no other considerations besides price. If every trucking company’s cost goes down by 5% due to tax cuts, then you can be sure that they will bid 5% less to move the freight: if they bid the same price, then another company will bid lower and win the business while still being profitable. In this hypercompetitive market, we would expect the tax cuts to almost entirely accrue to customers in the form of lower trucking prices.

Next, let’s think about aftermarket aerospace parts. Due to FAA safety regulations, there is often only one company that can fill an order if a cargo wench on a Boeing (NYSE:BA) 737 needs replacement. If this company’s costs go down 10% (or 20%), then there is no competition that means that it needs to bid 10% less for the business. If it keeps its price quote constant, then it will win the business (since it’s the only company that can supply the product) and will retain the whole benefit of the tax cuts.

In reality, many industries fall somewhere between these two extremes. Investors in individual companies need to understand fundamental industry dynamics in order to determine how much benefit they will see from the tax cuts. To the extent that companies compete solely based on price and operate in competitive industries, investors will see little benefit due to lower taxes. To the extent that a company’s brand, network effects, or excellent service (as opposed to price) convince buyers to choose their product over those of competitors, investors will see benefits.

Investors in broad index funds, or at least those with a diversified stock portfolio, need to ask a different question – how do after-tax earnings react to changes in tax rates over time? Will tax cuts lead to higher corporate earnings over the long run, or will the cuts be passed on to consumers? Will equity investors enjoy higher earnings and returns as a result?

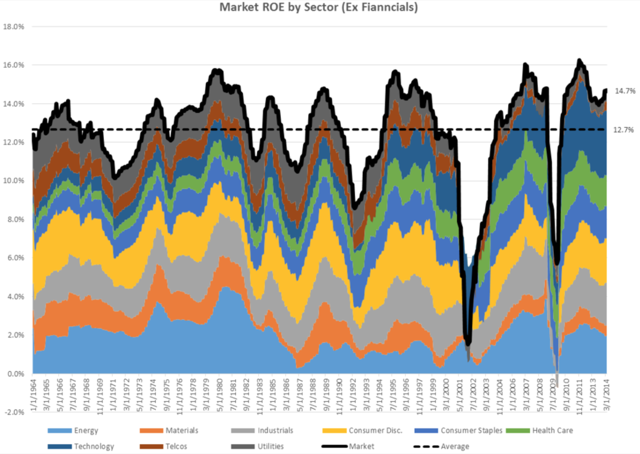

To answer these questions, we will look at after-tax returns on equity for large US businesses. This is the most important measure of profitability – how much money does $1 of investment generate after tax? If this number trends up (possibly because of increased market power of US businesses signaling low competition) or shows clear jumps when the corporate tax rate is changed, we can assume that tax cuts will have a large effect on corporate earnings. On the other hand, if returns stay the same over time no matter what, we can conclude that US businesses are very competitive and that tax cuts won’t lead to markedly higher earnings. Here’s the chart of ROE since the mid-1960s (from Investor Field Guide):

Even with your naked eye, you can see that earnings as a percentage of book value have been remarkably constant throughout economic cycles since the mid-1960s. The return in any year jumps around based on how the economy is doing in the short term, but the average remains at 12.7% over time.

What does this data tell us? On aggregate, US companies viciously compete against each other, driving after-tax returns on their investments to around 12.7% through economic cycles. Competition in the marketplace matters more than the tax rate or whoever is in political office. For reference, corporate tax rates were between 46-50% up until 1986 and have been around 35% since – in the face of lower taxes, the average after-tax ROE has remained the same. There’s no reason to expect that US business won’t earn around 12.7% on their equity over the next 10-20 years. When you look at the data, all you can see is the result of competition; tax rates and every other factor fall by the wayside.

This obviously means that any run-up in stocks because of the expectation of tax reform has been unwarranted. However, that doesn’t mean that stocks are a bad investment. Perhaps they were undervalued before their recent run-up and still provide a good value today.

I prefer not to try to value the stock market precisely or give price targets. Instead, I use the methodology that Buffett uses in his famous Fortune article How Inflation Swindles the Equity Investor. If return on equity is constant over time, and if you know book value and reinvestment rates, then you can roughly compute the gains in intrinsic value for stocks over time. Let’s use his process with some updated numbers for the S&P 500 (all data furnished from the “Index Earnings” sheet found under additional info on S&P’s website):

Book Value: $798.64

Average ROE: 12.7%

Reinvestment Rate: 40%

Price (SPY): $2,716

Using this information, we can compute growth in equity and earnings at 5% annually ([$798.64*.127*.4]/$798.64) and shareholder payouts (dividends and share repurchases) of $76.20 (.127*.6*$798.64), which gives us a yield of 2.8% on the price of $2,716.

Using this rough framework, we estimate that a holder of US stocks could expect earnings power to increase by around 7.8%/year, owing to 5% growth in book value (and therefore earnings at constant ROE) and a 2.8% yield. Returns over time would equal this gain in earnings power after adjusting for any changes in valuation. While I think it’s dangerous to try to guess valuation changes, I will note that the market’s price/book ratio is higher than at pretty much any time other than during the tech bubble. Low interest rates currently support these high valuations, as a 7.8% potential return in stocks looks decent compared to a 2.4% yield on ten-year treasuries.

This leads us to one important factor that hasn’t been discussed in great detail: all else equal and assuming a decently strong economy, tax cuts will lead to higher interest rates. Higher interest rates have huge effects on stock values, as Buffett’s article attests; he was calling stocks expensive at book value because interest rates were at 12%. Stocks currently trade at 3.4x book. If tax cuts do bring about interest rate increases, and there are indications that that is already happening, that will have a hugely negative effect on stock values, since a 7.8% potential return in stocks isn’t attractive compared to a 4-5% yield on treasuries. In this scenario, prices would almost certainly drop in order to keep the expected return on stocks much higher than that of treasuries.

Because of these reasons, an investment in the broad stock market does not currently look appealing to me. Investors are risking large drawdowns, as they always are, but at this point, they can only expect 7-8% returns over time at most. If interest rates return to higher levels of 4% or so, equity returns would probably be much lower than 7%, even over a long period – 7.8% growth but a revaluation to a more normal P/B ratio of 2.7x (a 20% contraction from 3.4x) would lead to only 5.4% returns over ten years. I don’t like expected mid-single digit returns in exchange for prospects of a 50% drawdown. I would rather make some select investments while keeping some extra cash and waiting for better prices.