By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

The Dallas Fed’s Forth Quarter Energy Survey, released today, portrays an industry that is turning increasingly somber. The data is based on responses of executives (names are not disclosed) of 170 energy companies – 111 exploration and production (E&P) companies; and 59 oil field services companies – located or headquartered in the Dallas Fed’s district, which covers Texas, northern Louisiana, and southern New Mexico and includes the most prolific shale oil-and-gas field in the US, the Permian Basin.

This time, there were additional questions, including on the reasons for “flaring” of natural gas in the Permian Basin. Natural gas is so abundant in the hydrocarbon mix produced at these wells (“associated” natural gas), and natural-gas pipeline takeaway capacity is so insufficient, that the surge in production led to the collapse of the price of natural gas in the area, reportedly dropping below zero on occasion. And it led to a record amount of natural gas getting flared in 2019.

Flaring large amounts of gas is a waste of natural resources, a source of air pollution, and a big financial drag for the already struggling oil-and-gas companies, investors, and banks.

To get a better handle on this, the Dallas Fed asked what the executives thought “the main reasons for the increase” in flaring in 2019 were (multiple choice, with the option to “check all that apply”):

- 73%: insufficient pipeline take-away capacity for gas

- 49%: lack of gathering and processing capacity for gas

- 45%: processing and transportation fees for gas that exceed the value of the gas

- 15%: temporary outages/issues with gas infrastructure

Among the comments on flaring, which ranged across the spectrum, there was one that I think is particularly interesting, in part because it was a suggestion on how to solve this issue:

“As a small independent producer, I would like to see the Texas Railroad Commission [the state regulator of the oil and gas industry] do its job and prevent waste of resources. Flaring should be allowed only for a short time to test and clean wells up after they have been hydraulically fracked. Once this has occurred, if the operator cannot find gathering/pipeline options for its natural gas production, the well should be shut-in until takeaway capacity is available.

“This would not only prevent waste, but would also slow the pace of drilling, decrease field production and drive natural gas prices up to a reasonable level. Low production wells are going to be prematurely plugged, with the resource lost, if natural gas prices do not improve soon. With industry support, this would also be seen as a good-faith effort to reduce air pollution from this waste of resources.”

And if takeaway capacity can finally be built out, gas production in the Permian, at least in one executive’s vision, will have a big impact on the global LNG market: “Permian associated natural gas is a still-emerging story that will change the Western Hemisphere liquefied natural gas market once infrastructure can catch up with natural gas production.”

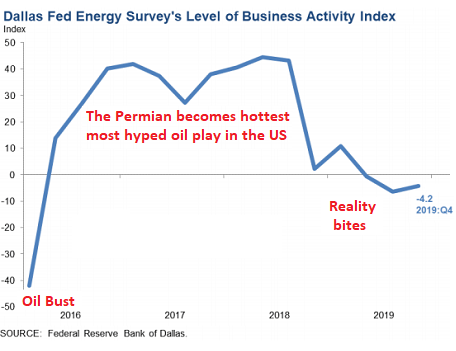

The Dallas Fed’s Business Activity Index, the broadest measure of conditions in the oil and gas sector in its district, has been in the negative for the third quarter in a row, at -4.2 (zero = no change). This came after the enormous boom that started in 2016, during the Oil Bust as the price of WTI had collapsed to below $30 a barrel, when the Permian became the hottest, most hyped shale oil play in the US. Note that for now, the index has barely dipped into the negative, compared to the levels in 2015 (chart via the Dallas Fed, red marks added):

The Business Activity Index by segment:

For E&P companies, the Business Activity Index was positive, at +5.4, up from zero in the prior quarter, indicating “modest growth.” Within that group, the oil production index rose to +24.7, and the natural gas production index rose to 15.6. But this surge in production is precisely what keeps oil and gas prices too low for these companies.

For oilfield services companies, the Business Activity Index plunged to negative -22. Within that group, the equipment utilization index was at -25.8 (unchanged), the index for prices received for services plunged to -24.5 (from 18.5) and the index for operating margins “plummeted,” as the Dallas Fed said, to -39.7 (from 24).

The overall Employment Index dropped to -10.0 (from -8.0). “We are having to divest properties in order to keep dropping employees,” one of the executives commented.

Given these conditions, the executives of these oil and gas companies now increasingly see expect to reduce their capital expenditures in 2020:

- 21% said they would “decrease significantly”

- 20% said they would “decrease slightly”

- 25% said there would be “no change”

- 26% said they would increase “slightly”

- only 8% said they would increase “significantly.”

This means that 41% of the companies would reduce their capital expenditures in 2020, and 34% would increase them, pointing at an overall decrease. Compared to the Oil Bust in 2015, this is still a relatively minor dip. And it wasn’t evenly distributed:

- 36% of E&P companies expect to cut expenditures, while 40% expect to raise them, with the remainder expecting no change. This indicates a slight increase in capital expenditures.

- But 49% of oil field services firms expected to cut capital expenditures, while only 24% expect to raise them, indicating a substantial cut in capital expenditures.

Investors and banks have lost their appetite to fund these cash-flow negative operations, according to several comments, including these:

- “The capital markets for oil and gas remain extremely difficult. The risk appetites of the banks for energy lending are much lower.”

- “I have noticed a significant investment decrease by oil and gas professionals. This may be partially attributed to the serious erosion of investment capital in listed securities. Many nonconventional shale wells are not achieving production expectations, thereby constricting cash flow for new wells and projects. Natural gas prices are insufficient to justify reworking old wells, which further constrains cash flows. The future seems uncertain.”

The Dallas Fed’s Oil Patch is not that unlike other oil-and-gas producing areas in the US, except that few experienced the boom starting in 2016 that the Permian experienced. Across the US, the oil-and-gas industry is feeling the pain, but not nearly to the extent felt in 2016, when the price of WTI dropped below $30 a barrel. Today, it’s over $60 a barrel. This makes a world of difference. But it’s still too low for the shale oil industry; and the price of natural gas, except for a few local spikes, has remained punishingly low for years.