by John Mauldin

There is an inflationary connection among energy, housing, and wages.

Louis Gave, co-founder and CEO of Gavekal Research, recently said that most economic activity is simply transformed energy of one sort or another. Modern economies developed as we found more efficient energy sources, moving from coal to oil to natural gas and nuclear.

Now we want to transition from carbon to renewables like solar and wind. This may ultimately bring great benefits, but for now it has produced under-investment in fossil fuel production capacity.

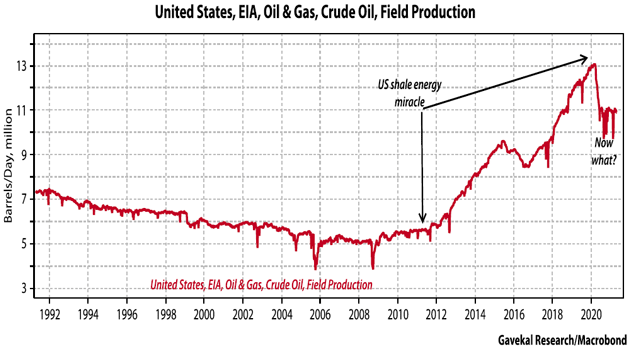

Just look at US shale production. It plunged last year and hasn’t yet recovered.

Source: Gavekal

This may be a problem because inventories are low and fuel demand is rising as more people begin moving around again.

We can import oil to make up for lost domestic production, but that will add to the trade deficit and weaken the dollar (which is also inflationary).

Meanwhile, other countries will also reopen, further increasing global oil demand. This will likely push energy prices significantly higher.

That alone is inflationary, but the follow-on effects may be more so.

Rising energy prices will sustain higher housing prices, since construction requires fuel to manufacture and transport large quantities of heavy, bulky building materials.

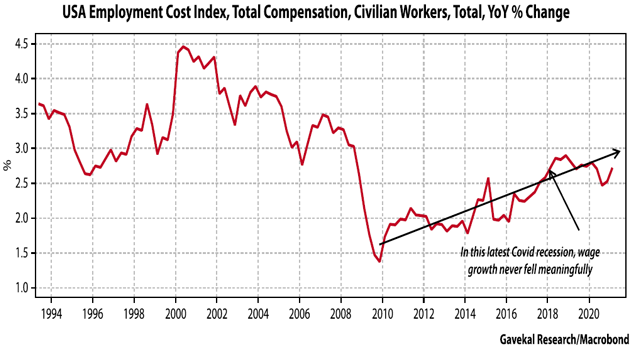

As housing becomes less affordable, wages will have to rise. Prior recessions always saw wage growth slow, if not reverse. We are trying to emerge from a recession in which wage growth never fell, which is historically unprecedented.

Source: Gavekal

You can see in the chart above how wages dropped in the 2000 recession and even more obviously in the 2008–2010 period.

Note that this doesn’t include the millions of Americans who lost jobs and whose wage income fell to zero.

In a typical recession, even those who keep their jobs see wages cut or at least don’t get raises. Not so this time. If you weren’t a laid-off service worker, you saw little effect on your pay.

So, generally speaking, wages haven’t dropped and are rising in some segments.

You might expect employers to respond with more automation—but we also have a serious microchip shortage, which is reducing automotive production. That, in turn, raises vehicle prices, further aggravating inflation. Replacing human workers with robots may not be a short-term solution.

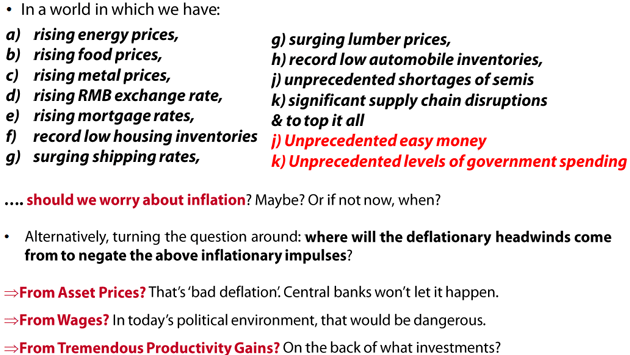

Louis thinks this adds up to a 180-degree change in the economic winds, from deflation to inflation. As he wrote it in his wrap-up slide at Mauldin Economics’ 2021 Strategic Investment Conference:

Source: Gavekal

Personally, I have been in the disinflation/deflation camp for decades. Any brief perusal of long-term interest rates and inflation since 1980 demonstrates that it was the right position. It was truly self-evident.

But looking at the current inflation data, you have to be willing to recognize that all trends, no matter how seemingly inexorable, come to an end.

Even the Federal Reserve, which has been adamantly protesting that any inflation was transitory and should be ignored, acknowledged in the minutes of its April policy meeting:

A number of participants suggested that if the economy continued to make rapid progress toward the Committee’s goals, it might be appropriate at some point in upcoming meetings to begin discussing a plan for adjusting the pace of asset purchases.

If I read that correctly, they are going to think about thinking about inflation at some point in the future.

Well, I damn well hope so. Announcing a policy of zero interest rates for 30+ months, no matter what, is the height of insanity. They have no way of knowing the future. What if things change? Remember the days under Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke when they said they were “data dependent”?

The Fed’s current policy has painted policymakers into a corner that is fraught with financial repression, destroys the value of savings, hurts retirees, and exacerbates income and wealth disparity—not to mention it helps maintain froth in the mortgage and housing markets, which need no help.

Far be it from me to criticize my economic betters, but they risk losing the narrative (read: confidence of the markets). They’ll also dramatically increase volatility in all sorts of markets from the unintended consequences of not admitting they don’t know what the future will bring.