“The high household debt load is the most important risk facing the financial system”: Bank of Canada Governor Poloz, another central banker that bemoans the effects of this handiwork.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

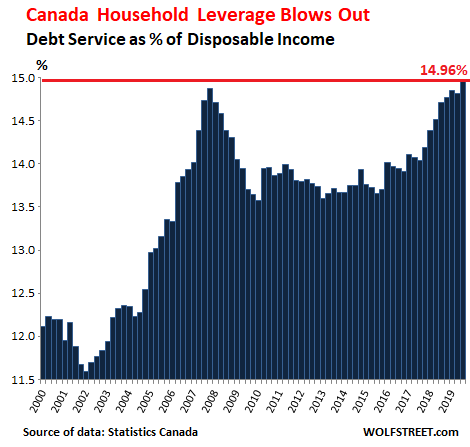

Canadian households, rated near the top of the most indebted in the world, accomplished something awe-inspiring: They got even more indebted and their leverage rose to a new record, according to data released today by Statistics Canada. The portion of their disposable income (total incomes from all sources minus taxes) that Canadian households spent on making principal and interest payments, including on mortgage debts and non-mortgage debts such as credit card balances, reached a new record of 14.96% in the third quarter, This record beat the prior record of 2007, and this happened despite still ultra-low interest rates:

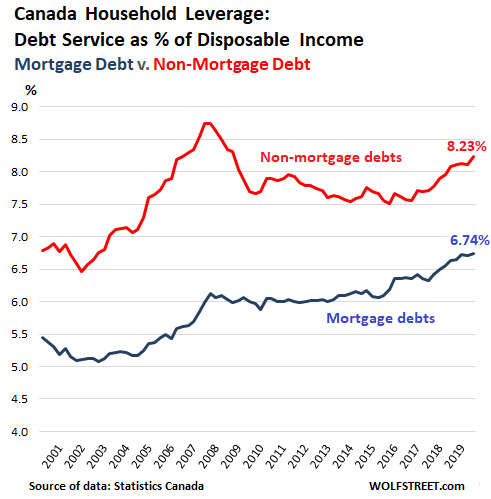

Mortgage debt was the driver behind this new record, as the portion of disposable income that Canadians spent to make interest and principal payments on their mortgages rose to 6.74%, the highest ever.

But these are aggregate numbers, and for some individual households, the burden is a lot higher. Based on data from the 2016 census, 67.8% of Canadian households own their home, and the ratio has been dropping. The remaining households rent, and they do not have a mortgage. And a portion of those who own a home do not have a mortgage either because they’d already paid it off. And another portion of homeowners only carries a relatively small amount of mortgage debt.

But among the remaining homeowners, particularly those who bought in recent years, the burden of their mortgage is heavy. And it’s this portion that everyone is worrying about, not the large number of other Canadian households. In the US, it was this portion that triggered the mortgage crisis — not the renters, and not the one-third of homeowners who’d already paid off their mortgages, and not those homeowners who’d paid down their mortgages significantly.

Non-mortgage debt, such as credit-card balances and personal loans, also increased, but did not take out the previous high. In the third quarter, debt service on non-mortgage debts reached 8.23% of disposable income, the highest since Q3 2008. This chart shows the two ratios separately:

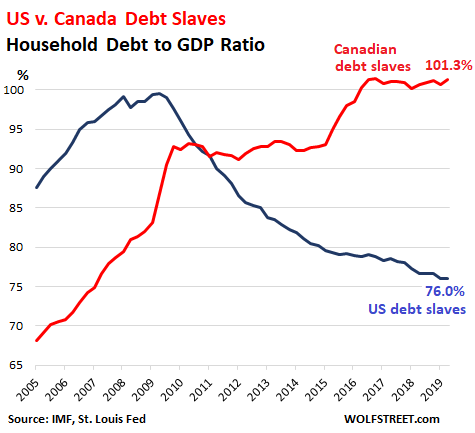

To compare the household-debt burden on the economy between Canada and the US, we can look at household debt to nominal GDP measures, each in their own currencies, which eliminates exchange rate fluctuations and inflation issues.

Americans were forced to deleverage during the mortgage bust and housing bust, and have never re-leveraged to the full extent, particularly with mortgage debt and credit card debts, which are barely higher than they were at the peak in 2007, but over those 12 years the economy had grown, and the population has grown, and the ratio of mortgage debt and credit card debt to GDP has declined sharply. The exception are student loans, which have totally blown out, and auto loans which have also increased faster than GDP.

Canadian households in aggregate never really experienced the full effects of the Financial Crisis in the housing market, and they weren’t forced to deleverage, and there was no lesson to be learned, and they have gone hog-wild on debt to fund their housing bubbles:

“The high household-debt load is the most important risk facing the financial system,” Bank of Canada governor Stephen PolozPoloz said in a speech on Thursday, whereupon he was challenged by BNN Bloomberg’s Andrew Bell during the press conference.

“But aren’t you the man who is to blame for that?” Bell asked. “You kept those interest rates so low all those years. You’re the main author of that bubble, aren’t you?”

Rather than just agreeing with the obvious, Poloz said this:

“A lot of things may have contributed to it, and certainly I would say keeping interest rates low, as many countries have had to do for over 10 years now.”

“If we go back to 2008/9/10, we had a lot of fiscal action, at the same time as monetary stimulus. And then globally, we saw enough of a recovery at that time in 2010 that governments decided, OK, we got things back on track, so we can consolidate on the fiscal side. Monetary policy makers figured we’d be coming out of it too.

“But then the economy faltered again, and we had the period that we call ‘serial disappointment.’ And it’s in that phase that monetary policy kind of got stuck in this very stimulative place, offsetting headwinds that are hard to really quantify by conventional analysis. But they’re obviously there.

“Even though the economy is at full employment, more or less, and inflation is on target, we’re there, but at really low interest rates from a historical standpoint. So those low interest rates are still stimulating against some contrary force. The fact inflation is on target suggests that the Bank of Canada has done its job.

“Now if there are side effects – one of them you mentioned – well, those are secondary effects. They’re not our prime mission. Our prime mission is to stabilize the economy and keep inflation on target. And we succeeded with that.”

And BNN Bloomberg’s Bell asked: “Are you worried that your legacy could be seen as leaving Canadians with a bunch of unsustainable debt.”

This time, Poloz was more direct – deny, deny, deny, because those were only “side effects.”

“No, I don’t see this household debt as unsustainable. That’s an important distinction. I see it as a vulnerability if a nasty shock came along and unemployment in Canada rose significantly.”

If that nasty shock came along, it “would be magnified” by the pile of household debt. “So we would have a bigger and probably more prolonged recession than we would if the debt was not there.” But of course, “even in the most extreme stress tests we can bring to the picture that combine the worst of 1981 with the worst of 2008, etc.,” with falling house prices, rising unemployment, and a big recession, “our financial system remains very resilient through those experiments.”

“Now that doesn’t say that there wouldn’t be people suffering from those recessions, of course, with high unemployment, possibly having to default on mortgages. I’m not dismissing that. That matters a great deal to me.”

To its credit, the Bank of Canada under Poloz has raised rates, starting in 2017, from 0.5% to currently 1.75%, to put a lid on the rampant housing bubbles in Greater Toronto and the Vancouver metro, and it has never dipped into the negative-interest-rate absurdity that has broken out in Europe and Japan, and it has worked with other regulators to put macroprudential measures in place that would tamp down on the ballooning household-debt bubble that was feeding the housing bubbles, but these measures came years too late, and what’s left now are the questions and worries over just how “sustainable” this household-debt bubble really is.