Grant’s Almost Daily, submitted by Grant’s Interest Rate Observer

Recovery room

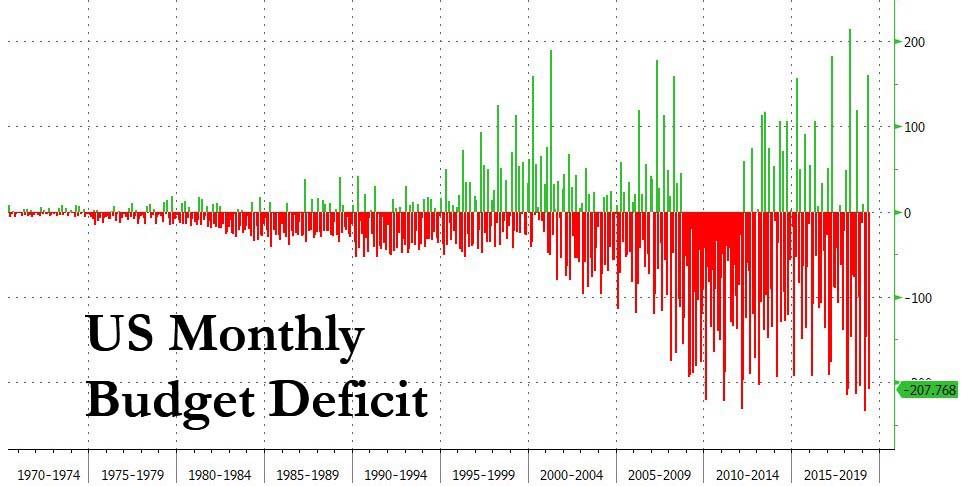

On Wednesday, the U.S. Treasury reported that Uncle Sam’s May deficit totaled a record $208 billion, bringing the 2019 year-to-date (the fiscal year begins on Oct. 1) shortfall to $739 billion. For context, full-year 2018 and 2017 saw gaps of $779 billion and $666 billion, respectively.

The explosion in government deficits during this extended epoch of economic growth is unusual. Typically, the government ledger improves during expansions, as revenues increase and the need for emergency spending diminishes. Thanks in large part to the Trump administration’s 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, that playbook is out the window. Instead, the White House’s own Office of Management and Budget pegs this year’s deficit at 5.1% of GDP.

The flowing red ink is set to continue, if estimates from the Congressional Budget Office are on the beam. The CBO pencils in deficits averaging 4.3% of GDP each year through 2029. That compares to a 50 year average deficit of 2.9% and 2.4% as recently as 2015.

Those persistent deficits will accelerate the pileup of Treasurys, as the CBO estimates that debt held by the public will jump an additional $12.7 trillion to $28.5 trillion by year-end 2029, equal to 92% of projected GDP from 78% currently and 66% in 2011.

There’s more where that came from. The Wall Street Journal reports today that “political support for taming deficits has melted away.” The electorate is increasingly comfortable with persistent shortfalls, as a January survey from Pew Research found that 48% of respondents favored prioritizing deficit reduction, down from 72% in 2013. Then, too, former IMF economist Olivier Blanchard argued at the American Economic Association in January that as government borrowing costs have generally lagged nominal GDP in the past 75 years, debt can essentially pay for itself as long as the economy keeps growing.

Indeed, as the post-crisis economic expansion rolls into its 120th consecutive month, tying the March 1991 to March 2001 period for the longest on record, The Journal concludes that the U.S. “is on course to test just how much it can borrow.”

That complacency is understandable, considering the bond market’s forgiving stance. Since 2002, federal debt held by the public has more than quadrupled, to $16.2 trillion. Yet, as the government’s books deteriorate, interest rates march lower, with the 10-year yield now at 2.13%, compared to 4.9% 17 years ago.

An interruption of the now decade long economic expansion would accelerate those fiscal shortfalls. Over the past 50 years, recessions have spurred deficit growth equating to 4% of GDP, on average. As widely noted, the yield curve suggests that something nasty may be in the offing (Almost Daily Grant’s, June 6).

Other indicators are likewise concerning. On Monday, The Dodge Momentum Index, a leading indicator for nonresidential construction, fell 9.2% year-over-year in May, with the commercial component down 16% from a year ago. Similarly, the Architecture Billings Index, which leads nonresidential construction activity by nine to 12 months, slipped into contraction in March for the first time since 2017. After a modest rebound in April (the most recent reading), American Institute of Architects chief economist Kermit Baker commented: “In contrast to 2018, conditions throughout the construction sector recently have become more unsettled.”

As the prospect of recession hovers and investors pile into the obligations of an ever-more spendthrift government, might an inflection point be approaching? The Feb. 9, 2018 edition of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer detailed the psychological shift between current conditions (underscored by the famous line reputedly offered by Dick Cheney: “Reagan proved that deficits don’t matter”) and the fallout of the 1946 to 1981 bond bear market, in which the 30-year Treasury was quoted at 14% in 1984, offering an inconceivable inflation-adjusted yield of nine percentage points.

In a bear market, new supply is perceived to be bearish, or at least not bullish (another tautology freighted with trading wisdom). Supply is thought to be bearish not, perhaps, because the supply of bonds is greater than the demand for bonds at prevailing yields and prices (though that is certainly true), but because the very thought of fixed-income securities has become repellent.

That attitude, and its opposite, are years in gestation.“The bond crop never fails” was how disgusted fixed-income investors expressed the free-floating hatred (or love-hatred, as the opportunities for reinvestment of coupon income were forever improving) of an asset class that had disappointed so many for so long.

From which it would follow that the Cheney/Reagan deficit doctrine is due for cyclical revision.