“The recovery is expected to be slow and uneven. It has not started quite yet based on the weak Class 8 orders in May.”

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

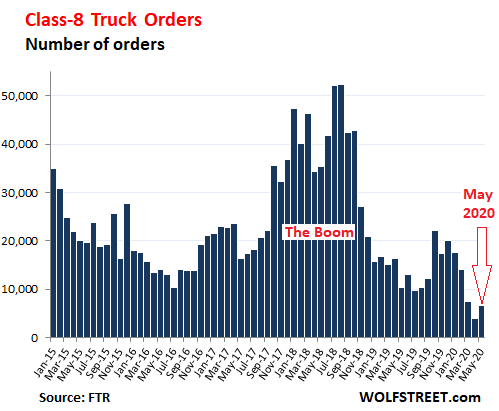

The last three months have been catastrophic for segments of the trucking business, after an already tough period that started in late 2018. In May, orders for Class 8 trucks – the heavy trucks that haul much of the goods-based economy across the US – plunged 37% from the low levels in May a year earlier, and by 81% from May two years ago, to 6,600 orders, according to estimates by FTR Transportation Intelligence today.

In April, orders for Class 8 trucks had collapsed by 73% to 4,000 units, the lowest in the data going back to 1996. In March, orders had plunged by 52% to 7,400 trucks, the lowest since 2010:

May was punctuated by the bankruptcy of Comcar Industries, operator of four trucking companies with about 950 employees, including 700 drivers: CCC Transportation, a bulk carrier, and CT Transportation, a flatbed carrier, both focused construction materials; CTL Transportation, a liquid bulk chemical transporter; and MCT Transportation, a refrigerated and dry van commodities carrier.

The privately owned company, whose largest shareholder was Pimco, plans to liquidate in bankruptcy court by selling off its trucking divisions, for which it had already lined up buyers.

In 2019, as a result of the sharp downturn in the freight business, declining mileage rates, and pressures from debt, hundreds of smaller trucking companies filed for bankruptcy. But Celadon’s chaotic collapse and bankruptcy in December that left some of its 3,000 drivers and 2,700 tractors stranded in North America marked the largest truckload-carrier bankruptcy in US history.

The May plunge in orders reduced the 12-month total of Class-8 orders to 155,000 trucks, down nearly 70% from the 12-month total at the peak through October 2018 of about 500,000 trucks.

This may be about as low as it’s going to get. Economic activity is starting to pick up from low levels, and freight volumes have bottomed out as well, though “fleets remain reluctant to order trucks,” FTR said in the emailed statement.

“The recovery is expected to be slow and uneven. It has not started quite yet based on the weak Class 8 orders in May,” FTR said.

“Most of the country still had some severe restraints in place for part of May. It is difficult for fleets to plan for future equipment needs under these highly abnormal conditions,” Don Ake, VP commercial vehicles, said in the statement.

“Carriers are more worried about what’s happening today, about their manpower needs and short-term issues, than ordering trucks. The concern about the pandemic goes beyond just the business and economic anxieties and greatly diminishes fleet confidence,” he said.

“Expect Class 8 orders to rise gradually, as caution wanes and fleet buyers begin to focus on the second half of the year and equipment requirements,” he said.

US truck manufacturers suspended production in March due to the pandemic. This too has now become part of the theme in many industries: a supply-and-demand shock happening at the same time. Demand collapsed and supply was shut down due to the pandemic. This can make for some unpredictable dynamics afterwards.

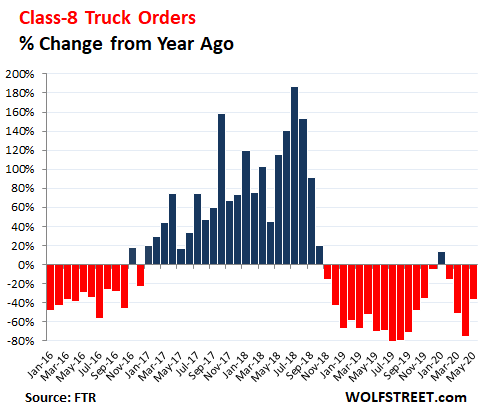

Class-8 orders – and much of the rest of the trucking business – went through a sequential double-whammy: First the freight recession in 2019 that followed the historic boom of 2018; and second, when orders were starting to bottom out in late 2019 and early this year, the pandemic.

The chart below shows the monthly percent changes of Class 8 orders from the same month a year earlier. January’s first year-over-year minuscule uptick after 14 months in a row of declines was wiped out in the following months:

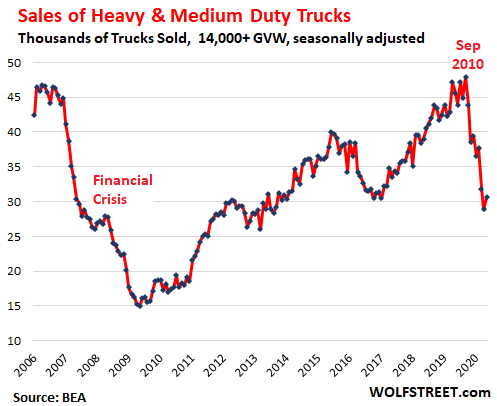

“Sales,” which lag “orders” by months, started skidding last October

The lag between the day an end-user, such as a trucking company, places the order, and the day the truck is delivered to the end-user spans many months. During the peak ordering panic of the boom in 2018, when the backlog at truck makers was huge, the lag between orders and sales could reach a year. So “sales” of trucks remained strong through much of the swoon in “orders” in 2019, as truck makers were working off their backlogs and booked record sales.

The Bureau of Economic Analysis reports sales of heavy trucks (over 33,000 pounds GVW) and of medium-duty trucks (classes 4-7, from 14,000 to 33,000 pounds GVW), all combined. Those sales peaked in September – over a year after Class 8 orders had peaked in August 2018. In October, sales started plunging.

In May, according to data by the BEA, sales of heavy and medium-duty trucks combined plunged by 32.8% year-over-year, to 30,600 trucks (seasonally adjusted) after having plunged 38.6% in April.

The May sales were for orders placed months before the pandemic. The impact of the pandemic – the historically low orders placed in March, April, and May – will not show up in the sales data for months:

During the Financial Crisis, sales of heavy and medium-duty trucks bottomed out at 15,000 units in April 2009, after having peaked in 2006. This time around, given the historic collapse in orders over the past three months, sales will likely bottom out near or below those levels sometime later this year.

And as the chart above shows, the recovery following the Financial Crisis back to the peak of sales before the Financial Crisis in 2006 took 13 years.