Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, http://www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

After truck manufacturers eat up their backlogs, then what?

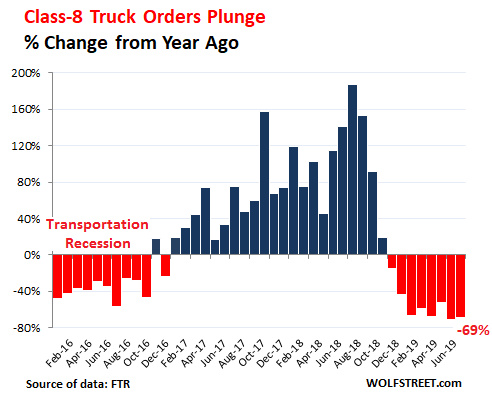

Orders for heavy trucks plunged by 69% in June compared to June last year, to 13,000 units, after having plunged by 71% in May, to just 10,400 units, FTR Transportation Intelligence reported today. It was the eighth month in a row of year-over-year declines. So far in 2019, the year-over-year declines in orders for Class-8 trucks ranged from -52% to -71%, which, as FTR said in the statement, makes it “the weakest six-month start to a year since 2010”:

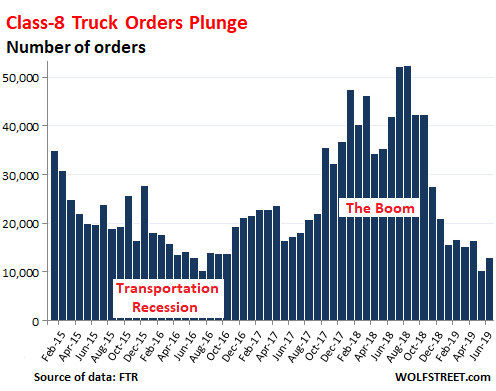

Orders for Class-8 trucks experienced a historic boom last year, reaching over 52,000 orders in both July and August, in a burst of ordering amid what was then called a “capacity panic.” But this boom is now getting unwound:

A year ago, nearing the peak in orders, FTR explained how the circularity of surging orders and subsequent delays in getting these trucks built, as factories are operating at capacity, leads to even more orders and even greater delays – the boom-and-bust cycle of the industry:

“There is an enormous demand for trucks due to burgeoning freight growth and extremely tight industry capacity. However, supply is severely constrained because OEM [Original Equipment Manufacturers] suppliers cannot provide the needed parts and components required to build more trucks fast enough. This bottleneck is causing fleets to get more orders in the backlog in hopes of getting more trucks as soon as they are available.”

Now the cycle has turned. These trucks that were ordered during the ordering panic last year to meet the capacity crunch last year are now on the road, and this increased capacity comes just as freight volume is falling, leading in practically no time from “capacity panic” to overcapacity.

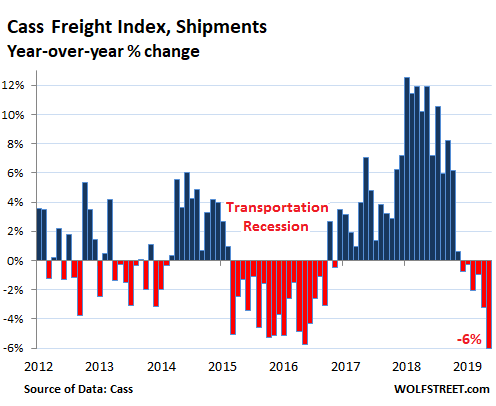

Freight volume in the US by all modes of transportation – truck, rail, barge, and air – has been declining on a year-over-year basis since December last year. According to the Cass Freight Index for Shipments, volume fell 6% in May, the sharpest decline since November 2009:

Increased capacity and declining demand are putting pressure on freight rates. The national average spot rates for hauling flatbed trailers and van trailers in June plunged about 18% from a year ago, to respectively $2.31 per mile and $1.89 per mile, according to DAT Trendlines. Contract rates, usually available only to large trucking companies with big stable clients, such as national retailers, have begun to edge down as well.

The decline in spot rates squeezes smaller trucking companies that depend on them. With fewer loads available to haul and less money per mile, it’s going to get tough for some of them, and the idea is to hang on until the cycle turns.

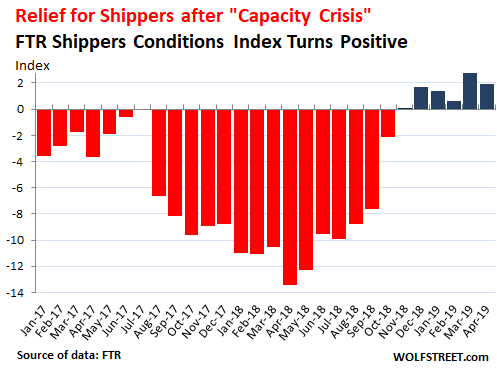

But there is always another side to it: Shippers – such as manufacturers or retailers – are breathing a sigh relief after last year’s crunch. The FTR Shippers Condition Index, which tracks shipping conditions from the shipper’s point of view, had been deeply negative until late last year. Then as capacity increased and freight volume began to back off, the SCI for November turned positive – the first positive reading since August 2016. The most recent SCI, released June 24, showed the sixth positive reading in a row:

The SCI tracks freight demand, freight rates, fleet capacity, and fuel price and combines them into an index value. A positive index value signals “good, optimistic conditions” for shippers. A value around zero represents neutral operating conditions. A negative value signals “bad, pessimistic conditions” for shippers. According to FTR, “double digit readings (both up or down) are warning signs for significant operating changes.”

The frenzy in transportation last year was caused in part by companies trying to front-run potential tariffs by ordering more merchandise. This sudden surge in orders led to all kinds of capacity problems, and it also led to the subsequent inventory pile-up in warehouses around the country that will eventually be worked off via a reduction in orders – and therefore a reduction in shipments.

The tsunami of orders for Class 8 trucks last year created a historic backlog for manufacturers – Peterbilt and Kenworth, divisions of Paccar [PCAR]; Navistar International [NAV]; Freightliner and Western Star, divisions of Daimler; and Mack Trucks and Volvo Trucks, divisions of Volvo Group. The plunge in orders since them means that these truck makers are now living off that backlog, and that the backlog is dwindling. FTR expects the backlog to fall below 200,000 units.

This is the time of the year when the model year changes, with truck makers ending production of 2019 models and opening up orders for 2020 models. But this is now fraught with its own issues, due to the uncertainties of the tariffs. In the statement today, FTR’s VP of commercial vehicles Don Ake says that one truck maker already started taking orders for 2020 models, but that the other truck makers “apparently did not.”

“Most OEMs are reluctant to quote future trucks due to uncertainty over material costs,” Ake said. “Until the tariff situation is resolved, it is risky to quote prices for 2020. Fleets are also reluctant to accept material surcharges with this much ambiguity present.”

This adds to the industry-wide cacophony from trucking companies and railroads that the threat of potential tariffs last year, and the imposition of actual tariffs, and now the uncertainty over tariffs have not only contributed to the transportation sector’s outlier-boom-year of 2018 but also to the undoing of this boom in 2019. Read… Trucking Swerves Deep into Slump, from Red-Hot Boom. Smaller Truckers Hit Hardest