Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, http://www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

The price of rising interest rates.

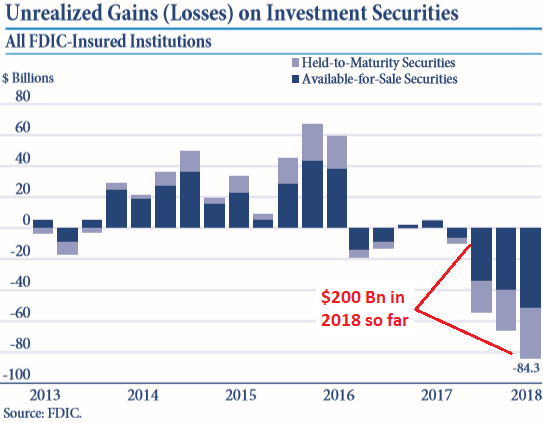

The FDIC just released the aggregated third-quarter performance metrics of the 5,477 banks and thrifts it insures. The amount of their combined assets ticked up to $17.7 trillion. These assets – mostly loans but also investments of all kinds – include $3.6 trillion in securities (not including the securities in their trading accounts). And banks got hit by the biggest quarterly losses on those securities since the first quarter of 2009.

Banks designate these securities either as “held-to-maturity” securities (valued at “amortized cost” or book value) and “available-for-sale” securities (valued at “fair value,” such as market value). For Q3, these were their unrealized losses – meaning, banks have not yet sold the securities:

- Available-for-sale securities: $51.5 billion in unrealized losses, or 2% of their amortized cost, as the FDIC said, “the highest loss level since first quarter 2009.”

- Held-to-maturity securities: $32.8 billion in unrealized losses.

- Both combined: $84.3 billion in unrealized losses.

Note the damage done in 2018, after years of big gains: $83.4 billion in Q3; $66.4 billion in Q2; and about $55 billion in Q1; for a total so far this year about $200 billion in unrealized losses.

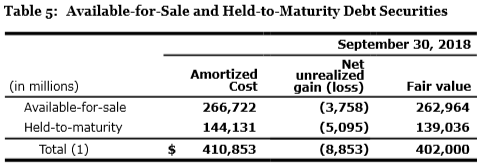

Not that this is a huge surprise. For example, Wells Fargo disclosed in its 10-Q filing for the third quarter that on its over $411 billion in available-for-sale and held-to-maturity security holdings, it suffered total unrealized losses of $8.85 billion so far this year. This includes net unrealized losses of $3.76 billion in available-for-sale securities and net unrealized losses of $5.1 billion in held-to-maturity securities (image from Wells Fargo 10-Q):

Wells Fargo explained that it was its $411 billion of available-for-sale and held-to-maturity debt securities, such Treasury securities, municipal bonds ($54 billion), mortgage-backed securities, corporate bonds, etc. that decreased by “$8.6 billion in balance sheet carrying value” since the beginning of the year. The reason: “primarily due to higher long-term interest rates.”

This $8.6 billion decrease in “balance sheet carrying value” largely bypassed the income statement.

Bond prices fall when yields rise; and in 2018, yields have ticked up across the yield curve. The weighted-average maturity of Wells Fargo’s available-for-sale debt securities was 6.2 years. So, with the 10-year yield rising from 2.4% to 3.05% over the nine months – a move of just 65 basis points – it nevertheless sent Wells Fargo’s unrealized losses soaring.

And as the FDIC data shows, with banks having incurred $200 billion of unrealized losses so far this year – of which $8.6 billion stem from Wells Fargo – it is not bank specific. All banks have this issue.

If banks don’t sell these securities but hold them to maturity, they will be paid face value at maturity. In other words, those unrealized losses dwindle and then disappear as the maturity date approaches, even under rising interest rates.

This assumes that there is no default or other impairment. But if those securities default, banks will take a loss, classified as an “other-than-temporary impairment” (OTTI).

Currently, defaults are still rare, as credit is still easy, rates are still relatively low, and investors are still chasing yield. So most companies, even risky ones, are not yet having trouble refinancing their maturing debts or borrowing more to make interest payments. And losses for bondholders are low at this point.

But credit has started to tighten a little. Parker Drilling is an example of what happens when the market loses interest in refinancing a company’s maturing debt. Parker Drilling has unsecured bonds that mature in August next year, but the credit markets lost interest. Unable to service and roll over this debt, Parker Drilling filed for bankruptcy. Holders of those unsecured bonds will get cents on the dollar. If a bank holds any of those bonds, it would have to take a loss on them. But this is still a rare case.

Wells Fargo confirms this. So far in 2018, it wrote down its debt securities by only $23 million due to “other-than-temporary impairment.” These OTTI losses at banks rise along with rising defaults among corporate and municipal debt, but this hasn’t happened yet.

Treasury securities that Wells Fargo holds will not see a default as the US government always has a buyer-of-last-resort in the market (the Fed). The only possible reason for a default of Treasury securities would be Congress’s refusal to lift the debt ceiling at the last moment. But not even Congress is that stupid.

So, losses on Treasury securities that are held to maturity are only temporary and will reverse as the maturity dates approach — during times of smooth sailing. However, if the bank is forced to sell those Treasury securities and other high-quality securities at fire-sale prices, as it might be during a liquidity crisis, which is what happened to some banks in 2007 through 2009, it may incur sharp and permanent losses on the securities it has to sell. These losses, in stressed times, can then combine with losses from other corners of the bank’s operations and balance sheet into a very toxic mix.