Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, http://www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

It’s so big: Soul searching in the Commercial Mortgage Backed Securities market.

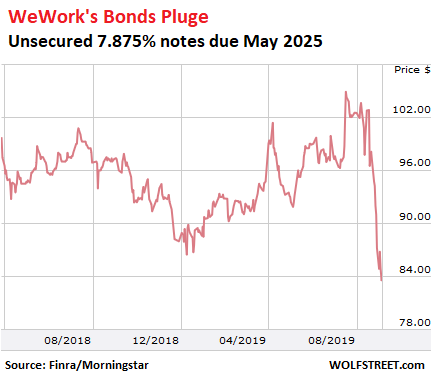

The $702 million in unsecured 7.875% bonds that WeWork issued in April last year traded at a record low on Friday afternoon, at 83 cents on the dollar, down 21% from 105 cents on the dollar six weeks ago before WeWork’s death spiral began. At this price, the bonds, which are due in May 2025, yield about 12.2%:

The original bet for buying that bond had been hinged on WeWork’s IPO. Folks were hoping that the company could raise $3 billion in equity capital in the IPO. This equity capital would have been the basis for a $6 billion leveraged loan from a consortium of banks. But without the $3 billion in equity capital, the loan would be way too risky and isn’t happening either. So the $9 billion the company had been counting on has moved out of reach.

WeWork’s debt would have been backed by a hoped-for sky-high market valuation in the future that would have allowed WeWork to sell ever more shares to raise ever more money, just like Tesla has been doing successfully for many years. And creditors count on this high share price.

With a high share price, a company can always raise new money and take care of its creditors. That’s why the bonds traded at 105 cents on the dollar before the IPO was scuttled. But WeWork has missed that money train. And for creditors, all bets are off.

Moody’s already withdrew its credit rating of WeWork in August 2018, because it had “insufficient or otherwise inadequate information to support maintenance of the ratings,” and washed its hands of it. Fitch downgraded WeWork to CCC+ with Negative Outlook, which pushed the rating into deep junk. And Standard & Poor’s downgraded WeWork to B- (here’s my plain-English cheat sheet for the credit rating scales of Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch).

Bets against the WeWork bond reached a record earlier this week, when short interest as measured by the amount of bonds on loan rose to $67 million, nearly 10% of the bonds outstanding, according to IHS Markit, cited by Reuters.

To short the bonds, intrepid investors have to borrow them from other investors and then sell those borrowed bonds, hoping that they can buy them back later at a lower price and profit from the difference. And they do have to buy them back, which can trigger vicious short-covering rallies, especially in something as illiquid as a WeWork bond.

Now everyone is combing through their Commercial Mortgage Backed Securities (CMBS) to see to what extent they’re exposed to WeWork. In some buildings WeWork is a big tenant, in other buildings WeWork is both the owner and a big tenant, and in that case there are two levels of risk.

According to Trepp, which analyzes CMBS, “WeWork is a top-five tenant at 36 office facilities behind more than $3.3 billion in CMBS debt across 50 deals.” WeWork loans account for about 4% of all office-backed loans in CMBS. “So that exposure is meaningful.”

About 78% of the WeWork-backed CMBS loans are fairly new, issued in the past three years, according to Trepp, “and have fairly minimal seasoning – so all of the loans are current on payment at the moment.”

“New York contains the largest WeWork CMBS footprint with total debt amounting to $1.5 billion across 29 notes,” Trepp says. California has the second largest loan exposure, at $803 million across 14 notes. Massachusetts is third with $230 million across three notes.

For example, in August, The We Company’s investment platform ARK – which had been formed in May to acquire, develop, and manage office properties to be mostly occupied by WeWork – acquired 600 California Street, a Class-A office tower in San Francisco’s Financial District for $330 million. It was the company’s first purchase in San Francisco. WeWork has been leasing 73,000 square feet in the 358,600-sqft building.

A $240 million loan used to fund the purchase has been securitized into a single CMBS (GSCG 2019-600C), with 11 tranches, of which 9 were offered, whose ratings range from AAA to B- and NR (not rated). In case of a default, the lowest tranches take the first loss.

In a deal like this, there is the risk that WeWork, the lessee, defaults on the lease; and there is the risk that the building owner, The We Company’s ARK, defaults.

“The biggest issue is not the pulling of the IPO per se, but the broader concerns about the firm’s viability,” Trepp says. “The worst-case scenario would be that the firm continues to burn through cash and can no longer support all of its lease obligations.”

“If that were followed by a period of non-payment of rent by WeWork, but physical occupancy and current payments by the firm’s sub-lessees, that would make for some interesting work for landlords and special servicers,” Trepp says.

These “special servicers” may already be licking their chops. When a CMBS loan defaults, or sometimes even when the building loses a critical tenant but the loan hasn’t defaulted yet, servicing gets switched from the master servicer to a special servicer, as laid out in the pooling and servicing agreement (PSA). The special servicer’s role is to figure out if the borrower can become current via a loan modification or a debt workout. Under many PSAs, special servicers have the right to purchase the building at a discount if the very same special servicer decides the loan cannot be brought current. So, yeah — this might get interesting.

And there are additional complications. WeWork is so large in some markets that a reduction in leasing demand from WeWork, or an outright unwinding of its leases, would put downward pressure on rents and prices in those markets, making it that much more difficult to sort through the fallout in the market from problems at WeWork.