By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

There has been huge hoopla about the Fed stepping into the markets and buying investment-grade corporate bonds and “fallen-angel” junk bonds, syndicated leveraged loans, CLOs (collateralized loan obligations), bond ETFs, and even junk-bond ETFs. The first intentions were announced in March and then expanded to include more asset classes and lower credit ratings. The Fed also announced that it would buy bonds and slices of syndicated loans directly from issuing companies, thereby providing emergency funding directly to companies that are solvent but cannot fund themselves because credit markets have frozen up. So what has the Fed actually done — and under what “authority?”

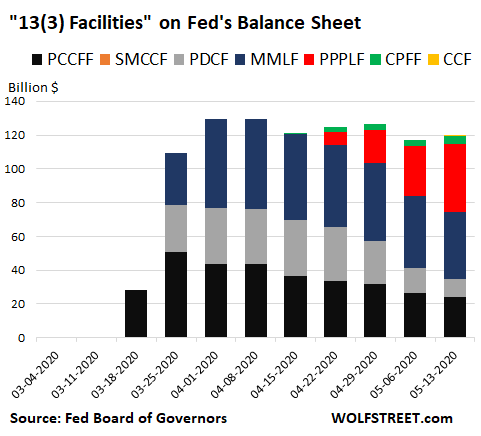

Three of the actions happened quickly: The money-market bailout (blue in the chart below), emergency funding for corporations (black), and loans to its Primary Dealers to be used to get markets to “function smoothly” (gray). They started showing up on the Fed’s weekly balance sheet in mid-March. But they soon began to taper off as the panic faded and as they were being unwound. In April, the Paycheck Protection Program loans to banks and some dollops of Commercial Paper started to show up. They filled the hole left behind by the shrinking first three.

The balance of all these alphabet-soup programs combined has declined from $130 billion on April 8 to $120 billion on May 13, as reflected on the Fed’s balance sheet released today. And none of the juicy stuff that the markets have so eagerly rallied upon – investment-grade and junk-rated corporate bonds and ETFs, CLOs, leveraged loans, etc. – happened until this week, and now it’s just a tiny wee bit, $305 million (with an M), the “CCF,” a yellow line on top of the green segment in the last column:

So why is the chart titled “13(3) facilities”?

That’s what Fed Chair Jerome Powell called them yesterday during the Q&A – “thirteen-three facilities,” is how he said it.

This “13(3)” refers to Section 13 paragraph 3 of the Federal Reserve Act, as amended in 1991 and then again in 2010 with the Dodd-Frank Act, which attempted to put some limits on what the Fed can do under this 13(3).

The section as amended allows the Fed, “in unusual and exigent circumstances,” to lend to individuals, partnerships, and corporations that are not banks (the Fed already lends to banks on a routine basis). According to Business Law Today, the limits set forth in the Dodd-Frank Act include:

Such lending must now be made in connection with a “program or facility with broad-based eligibility,” cannot “aid a failing financial company” or “borrowers that are insolvent,” and cannot have “a purpose of assisting a single and specific company avoid bankruptcy” or similar resolution.

In addition, the Federal Reserve cannot establish a section 13(3) program without the prior approval of the secretary of the Treasury.

Revised section 13(3) could be used to create facilities like the alphabet facilities of the financial crisis mentioned above [which is what we now face], but the intent of the revisions was to preclude loans like those to JPMorgan/Bear Stearns and AIG.

In its explanations of the alphabet-soup of bailout-and-enrichment programs, the Fed always refers to 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act as the source of “authority.” The Fed sets up Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) as Limited Liability Corporations. The US Treasury (taxpayer) provides the equity cushion. The Fed lends to the SPV to leverage it 10-to-1. The SPV buys the securities. And Powell refers to these creatures as “13(3) facilities.”

The alphabet soup of “13(3) facilities.”

The current generation of 13(3) facilities is still incomplete. The SPVs for TALF, municipal bonds, and others have not yet shown up. But so far, this is what the Fed has on its balance sheet, and what is depicted in the above chart. The amounts are what the Fed lent to these SPVs and don’t include the equity cushion from the Treasury (the colors refer to the chart above):

Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility (PMCCF, black): $24 billion, down from $50 billion on March 25. This SPV can lend directly to companies by buying bonds directly from companies, including certain “fallen angel” junk bonds; it can also buy portions of syndicated loans or bonds at issuance.

Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility (SMCCF): $0. This SPV can purchase corporate bonds, bond ETFs, and junk-bond ETFs in the secondary market, but hasn’t purchased anything yet.

Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF, gray): $10 billion down from $33 billion on April 15. These are loans to the Fed’s primary dealers that they use to buy securities to support the smooth functioning of the market.

Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (MMLF, blue): $40 billion, down from $53 billion on April 8. This SPV buys short-term commercial paper and other assets that money market mutual funds normally buy. During the panic, this allowed money market funds to sell those assets to meet redemptions.

Paycheck Protection Program Liquidity Facility (PPPLF, red): $41 billion, up from $0 a month ago. This SPV buys from banks the government-guaranteed loans they issued to small businesses under the PPP. The primary target seems to have been Wells Fargo, which refused to participate in PPP because it was bumping into its Fed-imposed limits on its assets (loans). By buying these loans, the Fed takes them off the books of the banks.

Commercial Paper Funding Facility LLC (CPFF, green): $4.3 billion, up from $0 on April 8. This SPV buys commercial paper, which are short-term corporate securities, to keep the corporate paper market liquid. The amounts are relatively tiny: $4 billion on a $7 trillion balance sheet.

Corporate Credit Facility (CCF, yellow): $305 million. Halleluiah, this SPV, managed by State Street as the custodian, has bought some corporate credit in the secondary market, some kind of corporate bonds, a whopping $305 million with an M.

But there are other signs that the gears are turning, that the mechanisms are getting set up. In addition to State Street, the Fed has hired BlackRock and PIMCO. They’re the custodians. The New York Fed gives them instructions.

The Fed appears to be in no hurry to get into corporate bonds and junk bonds and ETFs. Two months into it, and it has now bought $305 million, less than a rounding error on its balance sheet. But is sure was in a hurry with its jawboning about the program.

The whole 13(3) facilities combined amount to only $120 billion, on a $7 trillion balance sheet.

And yet each announcement about these 13(3) facilities over the past two months and what they might buy has been hyped at every twist and turn in the media. Hedge funds and banks and retail investors and whoever were chasing what they thought the Fed might buy. And this triggered a huge rally in investment-grade bond ETFs and junk-bond ETFs, and in corporate bonds and junk bonds, and leveraged loans, even as the Fed wasn’t buying anything.

But this allowed companies to issue record amounts of new debt in April and fund themselves that might otherwise not have been able to do so. Powell pointed out yesterday how successful this strategy was. He used two terms for it: “forward guidance” and the “announcement effect.” And he said, given how market have turned hot, that “it may mean that we actually aren’t needed.”