by John Mauldin

One difficulty in analyzing our economic future is the sheer number of potential crises. When so much could go wrong (and really right, when the exponential technologies I foresee get here), it’s hard to isolate, let alone navigate, the real dangers. We are tempted to ignore them all. Ignoring them is usually the right response, too. We can “Muddle Through” almost anything.

But muddling through isn’t the same as smooth sailing. It’s difficult, unpleasant, and often keeps you from looking for better opportunities. Then there are times when you can’t even muddle through. Instead, you find yourself emotionally at a dead stop or even going backwards. When surviving the storm is your focus, taking those “blood in the streets” buying opportunities is hard.

Which leads to this week’s letter. Almost every day I read scores of finance and economic newsletters, websites, articles, and books. A few articles on pensions hit my inbox this week and pursuing them led me to today’s topic.

But dear gods, I can remember writing a decade ago that public pension funds were $2 trillion underfunded and getting worse. More than one person told me that couldn’t be right. They were correct: It was actually much worse. (See, I’m an optimist!)

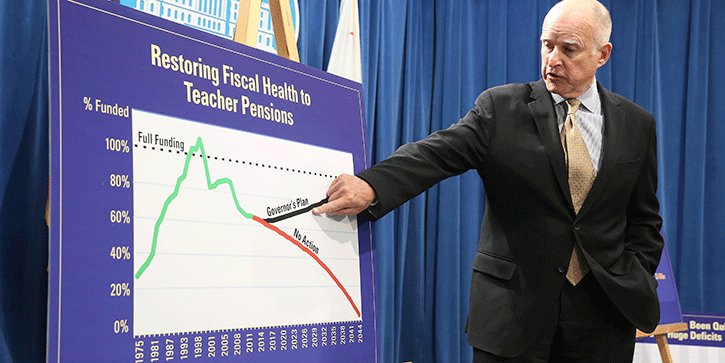

Two years ago I wrote that Disappearing Pensions are The Crisis We Can’t Muddle Through. Nothing since then has changed my mind. In fact, failure at all levels to even begin solving the problem is making it worse. The latest estimates, as we will see, suggest that it has gotten $2 trillion or more worse in just a few years.

Note we are talking here about a specific kind of pension: defined benefit plans, usually those sponsored by state and local governments, labor unions, and a dwindling number of private businesses. Many sponsors haven’t set aside the assets needed to pay the benefits they’ve promised to current and future retirees. They can delay the inevitable for a long time but not forever. And “forever” is just around the corner.

As we will see below, the numbers are large enough to make this a problem for everyone, even those without affected pensions. The problem is “solvable”… but the solutions will be problems in themselves.

Underfunded Future

Let’s begin with the enormity of the pension funding gap. As with the federal budget deficit, the large numbers are hard for our minds to process. They are also inherently uncertain. Let me explain.

A defined benefit pension plan for, say, a city’s police department, knows it owes a certain number of retirees certain monthly benefits for life. Their lifespans are fairly predictable when the pool is large enough. (I think new biotechnologies will change this soon, but that’s another topic.)

From that, it’s simple math to calculate how much money the plan should have right now in order to pay those benefits when they are due. But then the assumptions start. The plan must presume a future rate of return on the invested portfolio, an inflation rate, and in some cases future health care costs (medical benefits are part of many plans).

So, when we say a plan is “fully funded,” it may not be so if the assumptions are wrong. The amount a plan is underfunded could be much larger than the sponsor and auditors say. In theory, it could be smaller, too, but I have never seen that happen. The accounting rules that govern all this allow (some would say encourage) the sponsoring cities, counties, and states to understate their liabilities. This lets them avoid hard decisions like raising taxes, cutting benefits, or reducing other needed services.

Here’s a Wharton School note to place this huge number in context.

Sanitation workers, firefighters, teachers and other state and local government employees have performed their duties in the public sector for decades with the understanding that their often lackluster salaries were propped up by excellent benefits, including an ironclad pension. But Moody’s Investors Service recently estimated that public pensions are underfunded by $4.4 trillion. That amount, which is equivalent to the economy of Germany, accounts for one-fifth of national debt. It’s a significant concern for public employees who were banking on a fully funded retirement to get them through their golden years. The true number could be much higher. Whatever it is, filling it will be painful for somebody. Pensioners will receive lower-than-expected benefits, taxpayers will get higher-than-expected tax bills, or citizens will see government services cut. Or maybe all the above.

Then again, if you make more realistic assumptions on future returns the unfunded liability becomes $6 trillion according to the American Legislative Exchange Council. Total state and local annual revenues are only $3.1 trillion. Total property taxes are roughly $590 billion.

Here’s more grim news from The Heritage Foundation.

Overall, the American Legislative Exchange Council estimates that pension plans have only about a third of the funds on hand—33.7 percent—that they need to pay promised benefits. Some states have significantly lower funding levels, which means they are at risk of running out of funds in the near future.

Once a state or local pension plan runs out of money, taxpayers have to fund the pension benefits of retirees as well as the contributions of current employees.

Connecticut, Kentucky, and Illinois have the lowest funding ratios, at 20 percent, 21 percent, and 23 percent respectively.

Already, Illinois spends as much on pensions as it does on welfare and public protection (that is, police and firefighters) combined, and nearly half of its education appropriations go toward teacher pensions. If the state’s pension plans reach insolvency, pensions could become its single biggest cost.

These unfunded liability estimates are high because plan assumptions are too optimistic. Almost all public pension funds assume investment returns somewhere around 7% (and some as high as 8%+). A more conservative and realistic approach would force the state and local governments to fund those pension plans at a much higher level by either raising taxes or reducing services. What local politician will volunteer to do that? Better to find a consultant to tell you what you want to hear. There are plenty of them that will, for a reasonable fee, billed to the taxpayers.

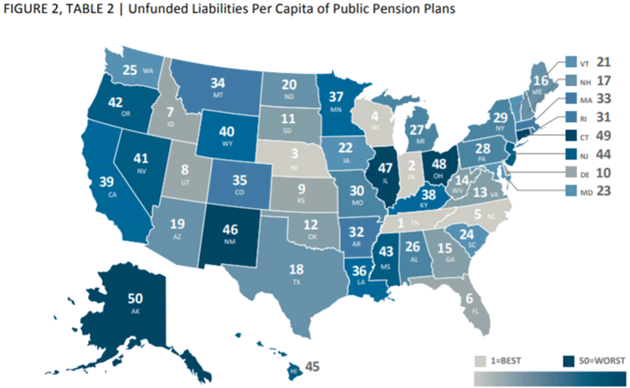

The following graphic shows how your state is ranked on a per capita funding basis. You can see the absolute numbers in the following table.

Source: Valuewalk

A further complication is that the taxpayers who might have to cover these amounts are mobile. They can move to other states with lower tax burdens, leaving behind those who, for whatever reason, can’t leave their states.

And to make it even more interesting, the beneficiaries often no longer live in the states that pay them. Retired public employees from the Northeast might live in Florida now, for instance. They can’t even vote for the people who govern their incomes.

The broader point: As with the federal debt, some portion of this unfunded pension debt is going to get liquidated in some manner. Any way we do it will hurt either the pensioners or taxpayers.

Pension Fund Underfunding Is a Local Problem

Thirty years ago Frisco, Texas, had fewer than 20,000 residents. Today its population is well over 180,000. Corporations from all over America are moving there. Tax revenues are booming. Frisco is the happy exception that simply grew faster than its pension liabilities.

Not so Dallas, whose Police and Fire Pension System was advertised as solvent just a few years ago. Now it is so deep in the hole that the mayor says plugging the gap would take almost a doubling of city taxes. (I bought my Dallas apartment after that news was announced but such an increase would have still made my taxes cost more than my mortgage. Can you say taxpayer revolt? It wasn’t the main reason, but it did factor in to my move.) Texas Monthly recently noted:

For those of us in Texas, with our gloriously high credit ratings and fervent allegiance to low taxes, restrained spending and conservative oversight of a robust Rainy Day Fund, the news that certain big cities around the country were in a heap of trouble might have elicited nothing more than a collective, if somewhat condescending, shrug. Except for one thing: Texas’s four biggest cities were all high on the list [of the worst 15 cities]. Dallas, which came in second, is on the hook for $7.6 billion, about five times the amount of its total operating revenues. Houston was fourth, with a $10 billion shortfall—equal to four times its operating revenues. Austin, at number nine, has $2.7 billion in liabilities, and San Antonio, ranked number twelve, is $2.3 billion short. That seems like very bad news for just about any Texan. Particularly since the vast majority of Texans now live in urban areas. How can a state known for fiscal responsibility have so many cities with empty pockets?

Will Frisco residents want to pay for the Dallas pension funding problems? Is The Woodlands going to want to pay for Houston’s problems? Is Indiana ready to pay for Illinois? Of course not. How much of a crisis will we need in order to recognize we are all in this together? Probably a lot bigger than you imagine.

Make the Children Pay

While arguments progress at the national level, state and local leaders must simultaneously pay their pension benefits, provide public services, and keep taxes to a level that doesn’t sweep them out of office or drive top taxpayers away. Not to mention keep the markets happy enough to sell future bond offerings, until such time as the Fed steps in as buyer-of-last resort. A tall order.

Given those choices, the usual answer seems to be “cut services and hope no one notices.” It is happening nationwide but California is in the vanguard, thanks to its massive pension debt. This is from a recent Brookings Institution note.

Pension and health-benefit costs are bending education finances in California to their will. The sheer magnitude of the rising costs is staggering. Large numbers of school board officials who participated in our survey indicate that the rising costs are meaningfully affecting educational services. For example, many report making cost-saving changes to district budgets that include deferred maintenance, larger class sizes, and fewer enrichment opportunities for students in response to rising pension and health benefit costs.

So in effect, today’s students are paying to keep benefits flowing to retired teachers and administrators.

Meanwhile, the Berkeley city council is taking criticism for prioritizing pension payments ahead of public works projects. Voters approved bond issues supposedly dedicated to infrastructure but the city is apparently not doing the work.

Nor is it just California. In a recent study, Bank of America analysts found an inverse relationship between infrastructure investment and pension fund contributions. Each additional $1 billion in plan contributions subtracts about $2.5 billion from state and local government investment.

We have multiple parties fighting over pieces of the same pie, all hoping that Uncle Sam will step in and save them. Uncle Sam may well do it, too, but it won’t remove the pain. It will just redistribute the burden, perhaps more widely, but the aggregate amount won’t change.

In my view, this leads to some kind of Japan-like deflationary recession. If we’re lucky, it will be mild and long. It won’t be fun but the alternatives would be worse.