Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, http://www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

The Fed has warned about them, and investors fear a run-on-the-fund.

The $1.3 trillion “leveraged loan” boom is coming unglued: Not because the junk-rated, highly leveraged, cash-flow-negative companies that issued these loans are massively defaulting – they’re not yet – but because investors are fleeing these instruments that had been super-hot for years, until October. They’re fleeing from loan mutual funds that hold these loans because they want to grab the “first-mover advantage” in an illiquid market; they want to be the first out the door before they get caught in a run-on-the-fund – with potentially catastrophic consequences for their cherished money.

These investors yanked a net of $3 billion out of US loan mutual funds and $300 million out of exchange-traded loan funds during the week ended December 19, in total $3.3 billion, the biggest outflow on record, according to Lipper. In the prior week, investors had yanked out $2.5 billion, which at the time had also been a record. It was the fifth week in a row of net outflows exceeding $1 billion, also a record.

Since the week ended October 31, the week all this started, the net outflow has reached $11.3 billion.

Loan-mutual funds sit on some cash with which to meet redemptions because selling a loan to meet redemptions can take a long time even in good times, but investors can get out of a mutual fund with the click of a mouse. This “liquidity mismatch” is very risky: When redemptions pick up momentum, the fund becomes a forced seller into an illiquid market where only a few vulture hedge funds (set up precisely for that opportunity) are willing to buy at cents on the dollar, even if the loans have not yet defaulted. Forced selling, the associated losses, and the inability still to meet redemptions can cause open-end mutual funds, such as these loan funds, to collapse.

Now these funds are flooded with record redemptions, and they’re selling loans to stay ahead of redemptions and maintain a cash cushion in order to avoid the fate that afflicted a number of open-end bond mutual funds during the Financial Crisis and during the oil bust a couple of years ago: a collapse of the fund when there is a run-on-the-fund.

This selling by these mutual funds has caused prices of these loans to drop. Note that “leveraged loans” carry a floating interest rate, pegged to Libor. In a rising interest-rate environment, the interest that a leveraged loan pays rises with Libor. So in this environment, these loans maintain their value, unlike fixed-rate bonds, whose prices decline as yields rise. That’s why these leveraged loans have become so hot among investors over the past three years.

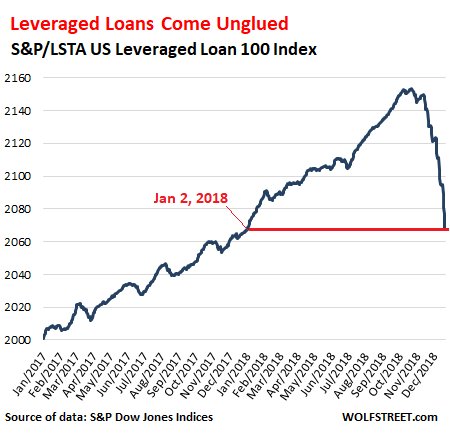

But on October 22, this market peaked, and then it began to fall apart. The S&P/LSTA US Leveraged Loan 100 Index, which tracks the prices of the biggest and most liquid loans, has since dropped 4%. That might not sound like a lot, compared to the declines in the stock market, but these loans are investments with a fixed face value and rising interest payments, and their price is not supposed to drop unless they’re at risk of default! These eight weeks of price declines wiped out the price gains of the prior ten months, putting the index back where it had been at the beginning of the year – and the wave of defaults hasn’t even started yet:

The Fed has warned and fretted about leveraged loans with increasing intensity since 2014, broadsiding them in ever greater detail and emphasis, including most recently:

- On October 24, when the market peaked, with a very specific warningabout how companies that issue leveraged loans are dousing investors with risks via four tactics: “Cov-lite” leveraged loans, “Incremental Facilities,” “EBITDA add-backs,” and “Collateral Stripping.”

- On December 2, in its first-ever Financial Stability Report, in which the Fed fingered business debts as the potential source of the next financial crisis, with leveraged loans being specifically cited as one of the major risks in that group.

Until October 22, investors have brushed off any concerns, and since 2014, when the Fed started warning about them, leveraged loans outstanding have doubled to $1.3 trillion.

Leveraged loans are issued primarily to fund:

- Leveraged buyouts (LBOs) where the acquirer, usually a private-equity firm, makes the acquired company borrow the money to fund its own buyout (hence “leveraged buyout”).

- Special dividends by the acquired company back to its PE firm owners. This form of asset stripping is called ironically, “recapitalization.”

Leveraged loans are traded like securities, but securities regulators don’t regulate them because they’re loans. Bank regulators consider leveraged loans too risky for banks to keep on their balance sheet, so banks arrange them with other leveraged loans, structure them, package them into Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLOs), and sell them to institutional investors. Or they sell the loans to loan mutual funds, pension funds, and other institutional investors, domestic or foreign. And all along, they collect hefty fees.

Thus, most of the risk of leveraged loans are with investors, not the banks. But banks are exposed to some extent, particularly when the market changes, and suddenly they cannot offload the loans and are stuck with them, which happened during the Financial Crisis; or when they cannot offload them at the prices envisioned and then have to sell them at big discounts and better terms for investors. And this is happening now. Rather than take a loss of this type, some banks are now choosing to hang on to the loans, hoping for better days.

According to Bloomberg:

A group of banks led by Goldman Sachs had to hold onto a $500 million loan backing the acquisition by First Reserve, a private equity firm, of a stake in Blue Racer Midstream LLC, a pipeline operator, people familiar with the matter said. A mix of direct lenders and infrastructure funds have expressed interest in the debt and Goldman is now likely to sell the loan to a small group of buyers separate from the syndicated market, one of the sources said. Barclays and RBC are also involved.

That delayed transaction, combined with others, means the banks will have to bear the risk of the loan prices falling further, as well as costs associated with holding the debt on their balance sheet.

This will be another cold shower for earnings at the biggest banks that arrange leveraged loans. But investors will eat the lion’s share of the losses, and to avoid this fate, these investors are now selling. There is always someone on the other end of each sale, and in this manner, the risks are getting shuffled around, and each time they get shuffled around, the prices drop.

But these are still the good times. The economy is growing, and companies are not yet massively defaulting on these loans. Credit is tightening, and it will be harder and more expensive for junk-rated companies to refinance existing debts when they come due, and a wave of defaults is expected, but hasn’t happened yet, and the impact of those defaults on leveraged loans is scheduled for later. What we’re seeing now is investors getting cold feet. It’s the first step.