But outside Italy, credit markets are sanguine, and no one says, “whatever it takes.”

By Don Quijones, Spain, UK, & Mexico, editor at WOLF STREET.

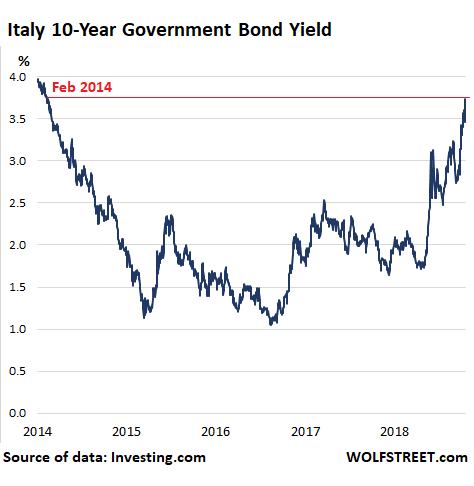

Italy’s government bonds are sinking and their yields are spiking. There are plenty of reasons, including possible downgrades by Moody’s and/or Standard and Poor’s later this month. If it is a one-notch downgrade, Italy’s credit rating will be one notch above junk. If it is a two-notch down-grade, as some are fearing, Italy’s credit rating will be junk. That the Italian government remains stuck on its deficit-busting budget, which will almost certainly be rejected by the European Commission, is not helpful either. Today, the 10-year yield jumped nearly 20 basis points to 3.74%, the highest since February 2014. Note that the ECB’s policy rate is still negative -0.4%:

But the current crisis has shown little sign of infecting other large Euro Zone economies. Greek banks may be sinking in unison, their shares down well over 50% since August despite being given a clean bill of health just months earlier by the ECB, but Greece is no longer systemically important and its banks have been zombies for years.

Far more important are Germany, France and Spain — and their credit markets have resisted contagion. A good indicator of this is the spread between Spanish and Italian 10-year bonds, which climbed to 2.08 percentage points last week, its highest level since December 1997, before easing back to 1.88 percentage points this week.

Much to the dismay of Italy’s struggling banks, the Italian government has also unveiled plans to tighten tax rules on banks’ sales of bad loans in a bid to raise additional revenues. The proposed measures would further erode the banks’ already flimsy capital buffers and hurt their already scarce cash reserves. And ominous signs are piling up that a run on large bank deposits in Italy may have already begun.

It’s not just the banks that are panicking; so, too, are Italian insurers which could face having to shell out more in advance taxes on their premiums as a result of the new budget, assuming it is ever given the green light by Brussels. “We need to be very careful dealing with these issues … because we are one of the pillars of the national system,” the chairman of Italy’s biggest insurer, Generali, said on Tuesday.

Global investors also have big reasons to worry. Italy’s government faces an eye-watering €270 billion worth of bond redemptions in 2019 alone. With interest on Italian government debt rising to its highest level in five years and its biggest margin buyer of the last three years, the ECB, exiting the market, it’s looking like a tall order.

The Bank of Italy is afraid that a vicious cycle is forming over the country’s debt costs. If market tensions don’t ebb, it warns, interest spending could surge above government estimates in 2019-20. Interest expenditures had fallen to €65.5 billion in 2017 from a high of €83.6 billion in 2012, helped along by the ECB’s buying of sovereign bonds as part of its QE program.

In 2012 the yield on Italy’s ten-year bond smashed through the 7% mark. Markets were in a frenzy. And then, Mario Draghi gave his “whatever it takes” speech and unleashed the world’s largest ever QE program.

But that program is ending this year, and at some point next year, the Eurozone’s benchmark interest rates are supposed to begin the long arduous path toward “normalization,” which makes the timing of this gargantuan showdown between Brussels and Rome even more auspicious.

The new big fear is that this month, either or both, Moody’s and S&P, will downgrade Italian debt two notches into junk territory. The potential implications of such a move, not only for Italy but for the European project as a whole, are so huge that many market players are discounting it as a possibility altogether.

“A downgrade to junk could trigger a full-blown (euro zone) crisis,” said Nicola Mai, a portfolio manager at PIMCO, the world’s largest bond investor. “…Which is why I don’t believe the agencies will do it, I don’t think they will want to be the ones causing a crisis in Europe.”

Iain Stealey, a fixed income portfolio manager at JP Morgan Asset Management, concurs. “It would be a very, very big decision, just given the size of the Italian bond market; it makes up something like a fifth of government bonds in the euro zone,” he said. In other words, contagion would spread across the Euro Zone like wildfire.

For the moment, however, that’s not happening. Whereas at the height of the Euzo Zone’s sovereign debt crisis Italy and Spain’s bond yields moved virtually in tandem, today a gulf has opened up between the two.

Since suffering political turbulence in 2016, Spain’s fortunes have diverged from Italy’s. The Catalonian crisis has deescalated. The new minority government, while perilously fragile, is staffed to the rafters with former senior eurocrats who can be counted on to take orders from Brussels. According to the FT, the country is even regarded by some investors as “semi-core,” in light of its strong economic growth, structural reforms and credit rating upgrades.

That may be pushing it a little. But it’s not just Spain that’s weathering the tide. Former crisis-country Ireland’s 10-year yield is just below 1%, while Portugal’s 10-year yield at 2.04% remains near historic lows — nothing compared to the wild gyrations it saw during the sovereign debt crisis when at one point it had spiked to 16%.

That the peripheral Eurozone bonds are not moving in sync with Italy’s this time might seem to suggest, as the FT posits, that investors do not regard Italy’s crisis as an existential threat to the Eurozone. That may be the best-case scenario — given how interconnected the Eurozone is and how large a footprint the Italian economy has. But if it plays out that way, and contagion remains contained, there may be no rescue forthcoming for Italy, just as the ECB’s Italian Chairman Mario Draghi warned last week. Of course, if Italy’s government backs down and agrees to play by Brussels’ rules, that may change, but for now there’s no sign of that happening. By Don Quijones.

The ECB has hired BlackRock, “a market power that no state can control anymore.” Read… Why’s the World’s Biggest Asset Manager Advising the ECB on the Health of EU Banks?