Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, http://www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

“The authorities should prepare contingency plans.” The big four banks are too exposed to mortgages. Even if the banks don’t topple, the economy will get hit hard.

In its latest report on Australia, the OECD focuses to a disturbing extend on housing, household debt, what the current housing downturn might do to the otherwise healthy economy, and what the risks are that this housing downturn will lead to a financial crisis for the big four Australian banks, an eventuality that it says “authorities” should make “contingency plans” for.

The big four banks are huge in relation to the Australian stock market and the overall economy: Their combined market capitalization, at A$341 billion, even after today’s sell-off following the OECD report – accounts for 26% of Australia’s total stock market capitalization.

How they dominate the stock market showed up on Monday after the release of the report:

- Common Wealth Bank of Australia (CBA): -2.98%

- Westpac (WBC): -3.38%

- Australia and New Zealand Banking Group (ANZ): -4.09%

- National Australia Bank (NAB): -2.54%

The overall ASX stock index on Monday dropped 2.27%.

These big four are heavily owned by Australian pension funds, retail investors, and the like and form a big part of the retirement nest egg of the nation. So a banking crisis that involves the Big Four matters on all fronts – and the OECD report even pointed out that a collapse in the share prices of the Big Four would itself impact the overall economy negatively.

The report (PDF) starts by explaining just how strong the economy is in Australia:

With 27 years of positive economic growth, Australia has demonstrated a remarkable capacity to sustain steady increases in material living standards and absorb economic shocks.

The labor market has been equally resilient, with rising employment and labor-force participation. Life is good, with high levels of well-being, including health, and education.

It expects “continued robust growth of around 3%” in the near future. And the OECD’s “resilience indicators” suggest “that there is no emerging downturn at present.”

But then there’s the housing bubble, household debt, and the banks that have funded this bubble and that households owe this debt to.

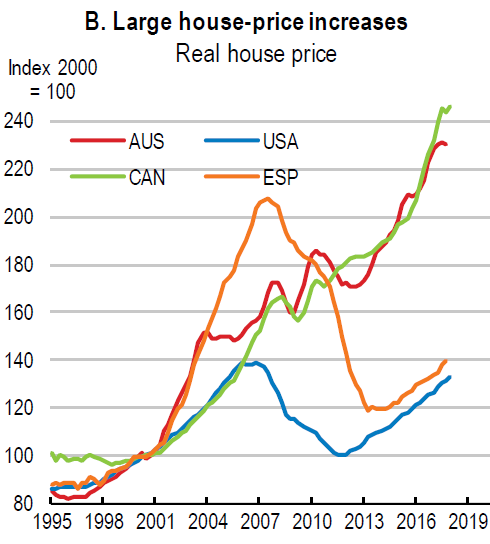

The charts below are from the report. The first chart compares inflation-adjusted house prices of the two most magnificent housing bubbles, Australia (red) and Canada (green), Spain (ESP), and the US. The index measures changes in price levels, adjusted for inflation. Clearly, Australia and Canada are in a world of their own, but Spain, whose bubble collapsed disastrously and led to numerous bank resolutions and bailouts, got close:

The Australian and Canadian two-decade long housing bubbles make the old US Housing Bubble 1 look practically infantile. However, with the US housing market being so much larger, and with US banks and financial products such as mortgage-backed securities being so interwoven in the financial world, the US housing bust that morphed into the US Financial Crisis became the Global Financial Crisis.

This is not going to happen with Australia and Canada: If they get into a financial crisis, they’re not big enough to drag the entire world into it.

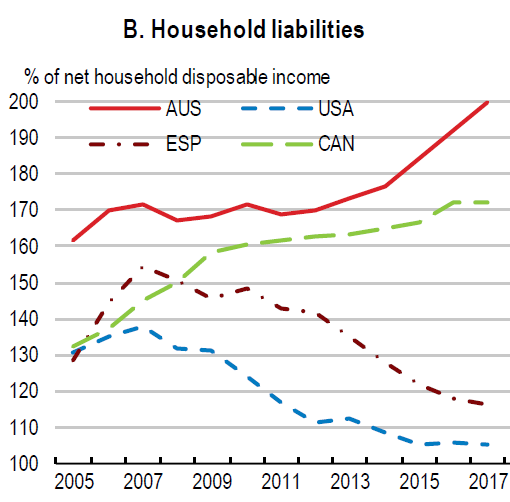

Australia’s household indebtedness, mostly tied to mortgages, and mostly owed to the above big four banks, reached 200% of net household disposable income, the highest ratio in the world. Even Canadian households can’t keep up with that. And US households, after the Financial Crisis, just fell of the mortgage wagon:

All this household debt has been incurred by households and provided by the banks on the assumption that the housing bubble would continue to inflate forever. But late last year, home prices began falling in Australia’s two largest housing markets – with prices in the Sydney metro down 9% and prices in Melbourne down 6% by last month. That was never part of the plan.

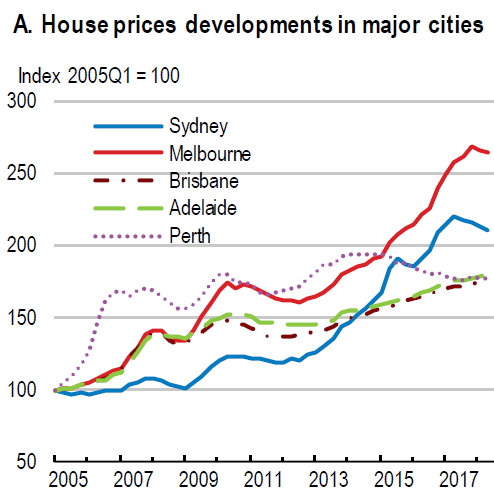

The OECD’s chart below depicts house prices in the big five capital cities. House prices in Perth (dotted line) have been in decline since 2014 due to the mining bust:

The ongoing sell-off in Sydney and Melbourne is “a welcome cooling of house prices,” the report says, which also lists some factors that contribute to it:

- “Prudential measures taken by the Australian authorities” to halt the “deterioration in lending standards.” This includes limits on interest-only loans, and many other measures.

- “A sizable pick up in new housing supply” – with new construction now flooding both markets at a record pace.

- “A fall off globally in the appetite for housing as an asset class,” which may, without naming names, refer to the sudden loss of appetite for Australian housing among Chinese investors.

- “Domestic rule changes and alterations to state-level taxes that may have deterred some foreign buyers.”

But the price declines haven’t done anything yet to fix the situation. The OECD warns that “though house prices have eased recently, they remain high in level terms (they have more than doubled in Sydney and Melbourne since 2005).”

And this housing downturn is happening even as Australia’s central bank (RBA) has kept interest rates at a record low 1.5%, which stimulated the housing market until it didn’t.

First, the report holds out hope: “The current trajectory would suggest a soft landing, but some risk of a hard landing remains.” But then it takes that hope away: “Past OECD work has found soft landings are rare.”

So how will it impact the banks?

The Australian “authorities” are in denial, the OECD seems to say ever so politely in between the lines: “Direct risk to the financial sector from mortgage defaults, triggered for instance by a hard landing in house prices or interest rates hikes, is viewed as limited by the authorities (for instance, see, RBA, 2018).”

More denials from the “authorities” that encouraged this housing bubble to form in the first place:

- “A particular feature of the housing loan market is that it comprises mainly variable rate mortgages. This makes household loan repayments more sensitive to movements in interest rates….” But that’s not considered to be an issue.

- And: “Risk of financial stress from the large numbers of mortgages with interest-only phases that are due to transition to principal-plus-interest repayment is also not considered substantial.”

Nevertheless, here’s what authorities should do, after they get through with their denials (emphasis added):

“The authorities should prepare contingency plans for a severe collapse in the housing market. These should include the possibility of a crisis situation in one or more financial institutions.” The contingency plans should include “a loss-absorbing regime (including bail-in provisions) in the case of financial-institution insolvency.”

Despite the big four banks passing the stress tests, “the possibility of financial-institution crisis should not be discounted entirely.”

So when this “financial-institution crisis” happens, who should pay? The OECD explains:

Insured account holders will be fine: “For account holders there is a deposit insurance scheme, the Financial Claims Scheme, which provides protection up to a limit of A$250,000 per account holder at each bank.”

But bank shares – that A$341 billion in current market cap – senior debt, and uninsured deposits may be bailed in:

“As regards the institutions, a crisis would put recently passed crisis-resolution legislation under test. Unlike in the United States or European Union, the legislation does not include explicit bail-in provisions on senior debt or deposits owed by financial institutions. This gives flexibility to adjust resolution plans to the specific characteristics of the crisis.”

“On the other hand, the absence of explicit bail-in provisions could slow down the speed of resolution and risk encouraging financial institutions to gamble for resuscitation. APRA has indicated that it will start a consultation on its loss-absorbing capacity framework in late 2018;”

“Loss-absorbing and recapitalization capacity should consist of a financial entity’s equity (shareholders) as well as debt instruments (certain bondholders and uninsured depositors) on which losses can credibly be imposed in a resolution.

Even if the banks don’t topple…

The report warns that “substantial impact of a hard landing in house prices on the wider economy may occur through other channels”: “If house prices collapse, consumer spending could suffer, via negative impact on wealth, including from exposure to bank shares, which would encourage deleveraging. Together with reduced housing-related expenditures, this would put pressure on the whole economy.”

“A large drop off in house prices could cut household consumption, prompt collapse in the construction sector, increase mortgage defaults, and freeze bank lending to business.”

In its own OECD bold, it says: “Financial supervisors and bank regulators should be prepared in the event of a hard landing in the housing market.”

And the RBA should hike its policy rates to remove the stimulus under the housing market: “In the absence of negative shocks, policy rates should start to rise soon. Monetary conditions remain very accommodative, with the risk of imbalances accumulating further if the low-interest rate environment persists. In the absence of a downturn, a gradual tightening should start as inflation edges up and wage growth gains momentum.”

So “a start to policy-rate normalization is now firmly on the horizon.” And “Though there are risks” to this “gradual tightening” envisioned by the OECD, “it could potentially bring welcome unwinding of the tensions and imbalances that have accumulated from the low-interest environment, notably housing-related issues.”

Which should have been done years ago before “the tensions and imbalances” got so big that they threaten to trigger the next financial crisis.

The house price declines in Sydney and Melbourne aren’t exactly slow motion anymore. Read… Update on the Housing Bust in Sydney & Melbourne, Australia